Showing archive for: “Public Choice”

Political Philosophy, Competition, and Competition Law: The Road to and from Neoliberalism, Part 3

As it has before in its history, liberalism again finds itself at an existential crossroads, with liberally oriented reformers generally falling into two camps: those who seek to subordinate markets to some higher vision of the common good and those for whom the market itself is the common good. The former seek to rein in, ... Political Philosophy, Competition, and Competition Law: The Road to and from Neoliberalism, Part 3

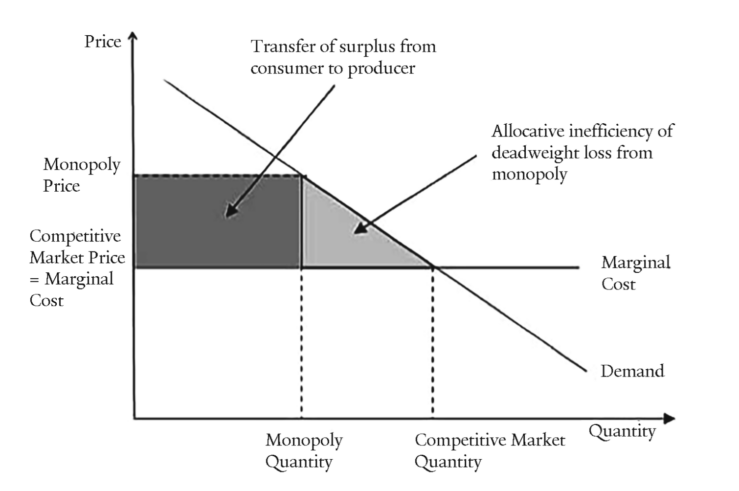

Toward a Dynamic Consumer Welfare Standard for Contemporary U.S. Antitrust Enforcement

For decades, consumer-welfare enhancement appeared to be a key enforcement goal of competition policy (antitrust, in the U.S. usage) in most jurisdictions: The U.S. Supreme Court famously proclaimed American antitrust law to be a “consumer welfare prescription” in Reiter v. Sonotone Corp. (1979). A study by the current adviser to the European Competition Commission’s chief ... Toward a Dynamic Consumer Welfare Standard for Contemporary U.S. Antitrust Enforcement

What is the Appropriate Role for State Antitrust Enforcement?

In the U.S. system of dual federal and state sovereigns, a normative analysis reveals principles that could guide state antitrust-enforcement priorities, to promote complementarity in federal and state antitrust policy, and thereby advance consumer welfare. Discussion Positive analysis reveals that state antitrust enforcement is a firmly entrenched feature of American antitrust policy. The U.S. Supreme ... What is the Appropriate Role for State Antitrust Enforcement?

Against the Jones Act

Economist Josh Hendrickson asserts that the Jones Act is properly understood as a Coasean bargain. In this view, the law serves as a subsidy to the U.S. maritime industry through its restriction of waterborne domestic commerce to vessels that are constructed in U.S. shipyards, U.S.-flagged, and U.S.-crewed. Such protectionism, it is argued, provides the government ... Against the Jones Act

Conflict of Interest in Prosecuting Police Officers: Examining the Incentives Facing District Attorneys

High-profile cases like those of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and Breonna Taylor in Louisville, Kentucky, have garnered attention from the media and the academy alike about decisions by grand juries not to charge police officers with homicide. While much of this focus centers on alleged racial bias on the part of police officers and ... Conflict of Interest in Prosecuting Police Officers: Examining the Incentives Facing District Attorneys

Ongoing Blog Series: The Law, Economics, and Policy of the COVID-19 Pandemic

The following is the first in a new blog series by TOTM guests and authors on the law, economics, and policy of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The entire series of posts is available at https://laweconcenter.wpengine.com/symposia/the-law-economics-of-the-covid-19-pandemic/.

Thank you, Stigler Center, for the Compliment. Now Here’s Why You’re Wrong.

This guest post is by Neil Chilson, Senior Research Fellow for Technology and Innovation at Charles Koch Institute and former Chief Technologist at the Federal Trade Commission. Is it rude to respond to a compliment with a rebuttal? I’m afraid that’s what I’m about to do. The antitrust reformers at the University of Chicago’s Stigler ... Thank you, Stigler Center, for the Compliment. Now Here’s Why You’re Wrong.

Putting Politics over Policy at the FCC

FCC Commissioner Rosenworcel penned an article this week on the doublespeak coming out of the current administration with respect to trade and telecom policy. On one hand, she argues, the administration has proclaimed 5G to be an essential part of our future commercial and defense interests. But, she tells us, the administration has, on the ... Putting Politics over Policy at the FCC

Correcting the Federalist Society Review’s Mischaracterization of How to Regulate

Ours is not an age of nuance. It’s an age of tribalism, of teams—“Yer either fer us or agin’ us!” Perhaps I should have been less surprised, then, when I read the unfavorable review of my book How to Regulate in, of all places, the Federalist Society Review. I had expected some positive feedback from ... Correcting the Federalist Society Review’s Mischaracterization of How to Regulate

Chevron and the Politicization of Law (or, Chevron Step Three)

A recent exchange between Chris Walker and Philip Hamburger about Walker’s ongoing empirical work on the Chevron doctrine (the idea that judges must defer to reasonable agency interpretations of ambiguous statutes) gives me a long-sought opportunity to discuss what I view as the greatest practical problem with the Chevron doctrine: it increases both politicization and polarization of ... Chevron and the Politicization of Law (or, Chevron Step Three)

The Collateral Order Doctrine and State Action Immunity: Salt River Power District, Antitrust Federalism, and the Burden of State-Supported Monopoly

On December 1, 2017, in granting certiorari in Salt River Project Agricultural Improvement and Power District v. SolarCity Corp., the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to consider “whether orders denying antitrust state-action immunity to public entities are immediately appealable under the collateral-order doctrine.” At first blush, this case might appear to involve little more than a ... The Collateral Order Doctrine and State Action Immunity: Salt River Power District, Antitrust Federalism, and the Burden of State-Supported Monopoly

Pai’s Right on Net Neutrality and Title II

As I explain in my new book, How to Regulate, sound regulation requires thinking like a doctor. When addressing some “disease” that reduces social welfare, policymakers should catalog the available “remedies” for the problem, consider the implementation difficulties and “side effects” of each, and select the remedy that offers the greatest net benefit. If we ... Pai’s Right on Net Neutrality and Title II