Showing archive for: “FCC”

Will the Courts Allow the FCC to Execute One More Title II Flip Flop?

The U.S. Supreme Court’s recent decision in Loper Bright v. Raimondo may have added a new wrinkle to the decades-long fight over whether broadband internet-access services should be classified as “telecommunications services” under Title II of the Communications Act. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has flip-flopped multiple times over the years on this hotly debated ... Will the Courts Allow the FCC to Execute One More Title II Flip Flop?

How This Supreme Court Term Might Affect the FCC’s Digital-Discrimination Rule

The recently completed U.S. Supreme Court session appears to have upended the administrative state in some pretty fundamental ways. While Loper Bright’s overruling of Chevron attracted the most headlines and hand-wringing, Jarkesy will have far-reaching effects across both the executive and judicial branches. Even seemingly “small” matters such as Ohio v. EPA and Corner Post ... How This Supreme Court Term Might Affect the FCC’s Digital-Discrimination Rule

FCC’s Digital-Discrimination Rules: Bridging the Divide or a Bridge Too Far?

The Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC) recently enacted rules to prevent so-called “digital discrimination” in broadband access are facing a significant legal challenge in the 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. Earlier this week, the U.S. Justice Department and the FCC submitted their brief on the matter. Now that the parties have made their “opening arguments” ... FCC’s Digital-Discrimination Rules: Bridging the Divide or a Bridge Too Far?

ICLE/ITIF Amicus Brief Urges Court to Set Aside FCC’s Digital-Discrimination Rules

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) recently adopted sweeping new rules designed to prevent so-called “digital discrimination” in the deployment, access, and adoption of broadband internet services. But an amicus brief filed by the International Center for Law & Economics (ICLE) and the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation (ITIF) with the 8th U.S. Circuit Court of ... ICLE/ITIF Amicus Brief Urges Court to Set Aside FCC’s Digital-Discrimination Rules

Net Neutrality and the Paradox of Private Censorship

With yet another net-neutrality order set to take effect (the link is to the draft version circulated before today’s Federal Communications Commission vote; the final version is expected to be published in a few weeks) and to impose common-carriage requirements on broadband internet-access service (BIAS) providers, it is worth considering how the question of whether ... Net Neutrality and the Paradox of Private Censorship

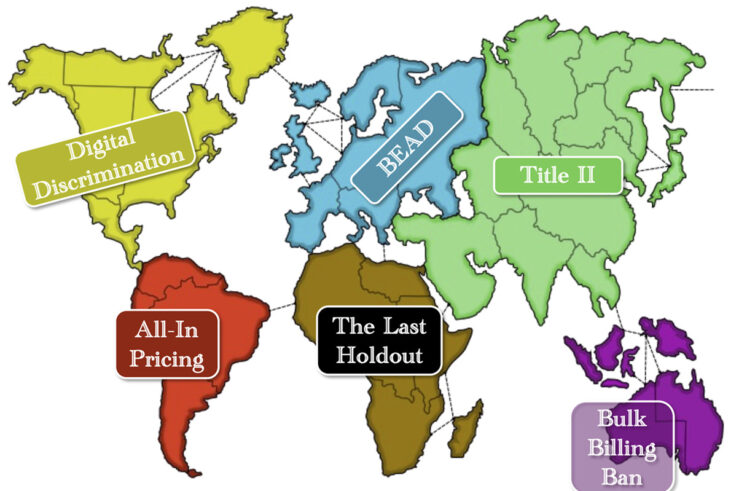

It’s Risk, Jerry, The Game of Broadband Conquest

The big news in telecommunications policy last week wasn’t really news at all—the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) released its proposed rules to classify broadband internet under Title II of the Communications Act. Supporters frame the proposed rules as “net neutrality,” but those provisions—a ban on blocking, throttling, or engaging in paid or affiliated-prioritization arrangements—actually comprise ... It’s Risk, Jerry, The Game of Broadband Conquest

Section 214: Title II’s Trojan Horse

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has proposed classifying broadband internet-access service as a common carrier “telecommunications service” under Title II of the Communications Act. One major consequence of this reclassification would be subjecting broadband providers to Section 214 regulations that govern the provision, acquisition, and discontinuation of communication “lines.” In the Trojan War, the Greeks ... Section 214: Title II’s Trojan Horse

Blackout Rebates: Tipping the Scales at the FCC

Cable and satellite programming blackouts often generate significant headlines. While the share of the population affected by blackouts may be small—bordering on minuscule—most consumers don’t like the idea of programming blackouts and balk at the idea of paying for TV programming they can’t access. Enter the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) with a bold proposal to ... Blackout Rebates: Tipping the Scales at the FCC

FCC’s Digital-Discrimination Rules: An Open Invitation to Flood the Field with Schlock

A half-dozen lawsuits have been filed to date challenging the digital-discrimination rules recently approved by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). These cases were consolidated earlier this month and will now be heard by the 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. This has the hallmarks of a significant case that will almost certainly involve the U.S. ... FCC’s Digital-Discrimination Rules: An Open Invitation to Flood the Field with Schlock

Are Early-Termination Fees ‘Junk’ Fees?

Cable and satellite companies often get a bad rap for early termination fees (ETFs). Consumer advocates portray them as “junk fees” or billing traps meant to cheat customers. And the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) appears to accept these allegations at face value, characterizing ETFs as “junk fee billing practices … that penalize subscribers for terminating ... Are Early-Termination Fees ‘Junk’ Fees?

The Curious Case of the Missing Data Caps Investigation

In an announcement that was treated to mild fanfare (meaning it was reported by certain tech blogs, but largely ignored elsewhere), Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Chair Jessica Rosenworcel asked her fellow commissioners in June 2023 to support a formal notice of inquiry (NOI) to learn more about how broadband providers use data caps on consumer ... The Curious Case of the Missing Data Caps Investigation

Slouching Toward Disconnection and the End of the ACP

It’s our first post of the New Year, and we’re having a hard time feeling the Hootenanny vibes. Rather than Congress taking a “new year, new you” approach to telecom policy, it seems that D.C. is starting the year with the “same old, same old” of brinkmanship. This time, with broadband subsidies. The Affordable Connectivity ... Slouching Toward Disconnection and the End of the ACP