Showing archive for: “Copyright”

Systemic Risk and Copyright in the EU AI Act

The European Parliament’s approval last week of the AI Act marked a significant milestone in the regulation of artificial intelligence. While the law’s final text is less alarming than what was initially proposed, it nonetheless still includes some ambiguities that could be exploited by regulators in ways that would hinder innovation in the EU. Among ... Systemic Risk and Copyright in the EU AI Act

Blackout Rebates: Tipping the Scales at the FCC

Cable and satellite programming blackouts often generate significant headlines. While the share of the population affected by blackouts may be small—bordering on minuscule—most consumers don’t like the idea of programming blackouts and balk at the idea of paying for TV programming they can’t access. Enter the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) with a bold proposal to ... Blackout Rebates: Tipping the Scales at the FCC

Oregon Should Beware the Right to Repair

The Oregon State Legislature is considering HB 3631, a bill that would ensure that consumers have a “right to repair” their electronics devices. The legislation would require that manufacturers provide consumers and independent repair shops access to relevant repair information, as well to make available any parts or tools necessary to carry out the repair. ... Oregon Should Beware the Right to Repair

State-Mandated Digital Book Licenses Offend the Constitution and Undermine Free-Market Principles

Various states recently have enacted legislation that requires authors, publishers, and other copyright holders to license to lending libraries digital texts, including e-books and audio books. These laws violate the Constitution’s conferral on Congress of the exclusive authority to set national copyright law. Furthermore, as a policy matter, they offend free-market principles. The laws interfere ... State-Mandated Digital Book Licenses Offend the Constitution and Undermine Free-Market Principles

A Few Questions (and Even Fewer Answers) About What Artificial Intelligence Will Mean for Copyright

Not only have digital-image generators like Stable Diffusion, DALL-E, and Midjourney—which make use of deep-learning models and other artificial-intelligence (AI) systems—created some incredible (and sometimes creepy – see above) visual art, but they’ve engendered a good deal of controversy, as well. Human artists have banded together as part of a fledgling anti-AI campaign; lawsuits have ... A Few Questions (and Even Fewer Answers) About What Artificial Intelligence Will Mean for Copyright

Rules Without Reason

In his July Executive Order, President Joe Biden called on the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to consider making a series of rules under its purported authority to regulate “unfair methods of competition.”[1] Chair Lina Khan has previously voiced her support for doing so.[2] My view is that the Commission has no such rulemaking powers, and ... Rules Without Reason

NEW VOICES: FTC Rulemaking for Noncompetes

On July 9, 2021, President Joe Biden issued an executive order asking the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to “curtail the unfair use of noncompete clauses and other clauses or agreements that may unfairly limit worker mobility.” This executive order raises two questions. First, does the FTC have the authority to issue such a rule? And ... NEW VOICES: FTC Rulemaking for Noncompetes

Welcome to the TOTM Symposium on FTC UMC Rulemaking

There is widespread interest in the potential tools that the Biden administration’s Federal Trade Commission (FTC) may use to address a range of competition-related and competition-adjacent concerns. A focal point for this interest is the potential that the FTC may use its broad authority to regulate unfair methods of competition (UMC) under Section 5 of ... Welcome to the TOTM Symposium on FTC UMC Rulemaking

Senate Bill Looks to Rebalance ‘Internet Freedom’ and Creators’ Rights

All too frequently, vocal advocates for “Internet Freedom” imagine it exists along just a single dimension: the extent to which it permits individuals and firms to interact in new and unusual ways. But that is not the sum of the Internet’s social value. The technologies that underlie our digital media remain a relatively new means ... Senate Bill Looks to Rebalance ‘Internet Freedom’ and Creators’ Rights

Fleites v. MindGeek Contemplates Significant Expansion of Collateral Liability

In Fleites v. MindGeek—currently before the U.S. District Court for the District of Central California, Southern Division—plaintiffs seek to hold MindGeek subsidiary PornHub liable for alleged instances of human trafficking under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) and the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act (TVPRA). Writing for the International Center for Law & Economics ... Fleites v. MindGeek Contemplates Significant Expansion of Collateral Liability

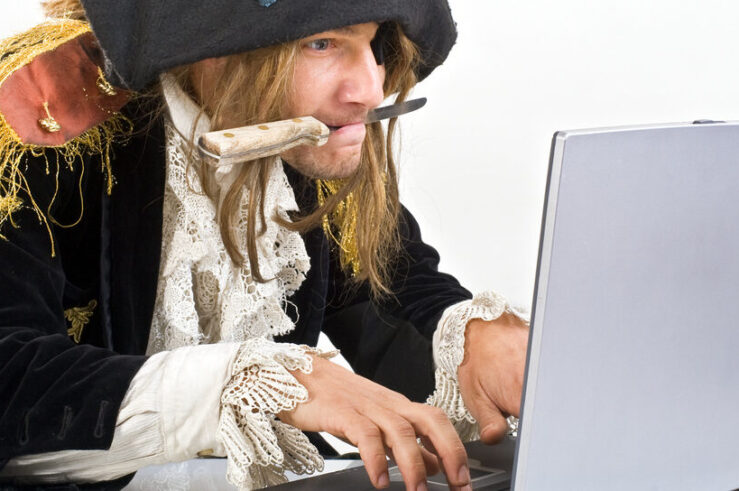

10 Years After SOPA/PIPA, Congress Still Needs to Address Online Piracy

Activists who railed against the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) and the PROTECT IP Act (PIPA) a decade ago today celebrate the 10th anniversary of their day of protest, which they credit with sending the bills down to defeat. Much of the anti-SOPA/PIPA campaign was based on a gauzy notion of “realizing [the] democratizing potential” ... 10 Years After SOPA/PIPA, Congress Still Needs to Address Online Piracy

Old Ideas and the New New Deal

Over the past decade and a half, virtually every branch of the federal government has taken steps to weaken the patent system. As reflected in President Joe Biden’s July 2021 executive order, these restraints on patent enforcement are now being coupled with antitrust policies that, in large part, adopt a “big is bad” approach in ... Old Ideas and the New New Deal