In an announcement that was treated to mild fanfare (meaning it was reported by certain tech blogs, but largely ignored elsewhere), Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Chair Jessica Rosenworcel asked her fellow commissioners in June 2023 to support a formal notice of inquiry (NOI) to learn more about how broadband providers use data caps on consumer plans. The FCC simultaneously opened a “data portal” soliciting “narrative information” about consumers’ experiences with data caps.

But more than half a year later, the NOI has not been issued and none of the information from the data portal has been publicly released.

Does that mean the FCC has lost interest in data caps? Not likely. They’re likely to make an appearance somewhere under the cover of “digital discrimination” or “net neutrality.” But until that day appears more imminent, let’s focus on what people mean by “data caps.”

The FCC has a long history of slapping prejudicial labels on innocuous conduct. If you are an internet service provider (ISP), you are labeled a BIAS (broadband internet access services) provider—because bias is bad, and neutrality is good. Providers who bill in monthly (rather than daily) increments, are mischaracterized as charging a “billing cycle fee,” or BCF, on consumers who terminate in the middle of the month. The FCC pejoratively calls BCFs and early termination fees (ETFs) “junk fee billing practices.”

This history continues. What the FCC calls “data caps” aren’t really caps at all, as the American Enterprise Institute’s Daniel Lyons points out (here and here):

[T]he phrase “data caps” is a misnomer. A cap implies a hard limit on the amount of data a customer may consume each month. That’s not an accurate description of most [usage-based pricing] offers, which are perhaps better characterized as pay-as-you-go plans. Customers pay in advance for a certain amount of data, and if they exceed that amount, they can purchase an additional amount. In other words, customers on these plans have unlimited data—they just pay for what they consume, just as they do with most other goods in society.

Lyons is correct. What most people think of when they hear “data caps” in policy circles is very different from how internet providers price consumer usage. To illustrate what I mean, let’s offer some simple examples.

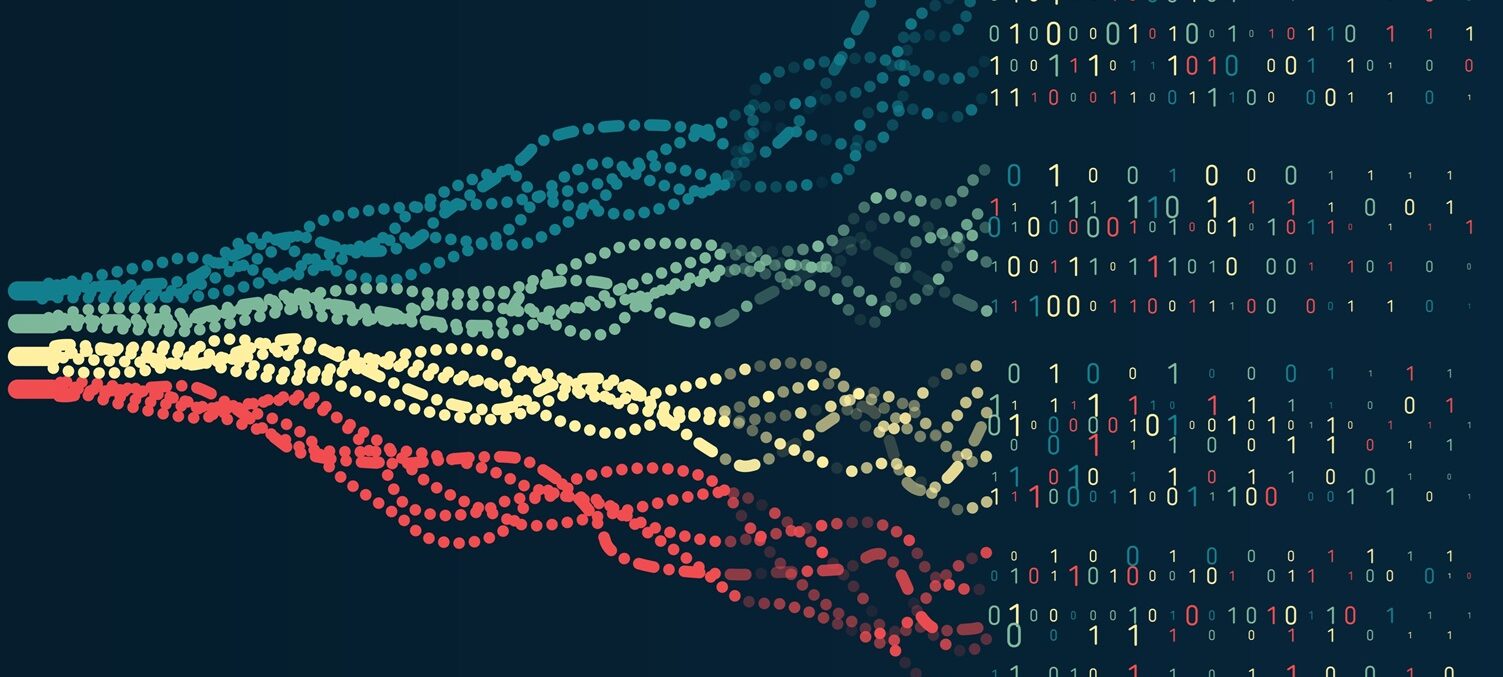

Consider a hypothetical case of a typical consumer in an all-you-can-eat data plan (Figure 1). Under this plan, the user pays an upfront flat fee for unlimited data use. The flat fee is equal to the consumer’s willingness to pay for unlimited data. This is equal to the area under the entire demand curve (A + B). Because the price per unit is zero, the consumer will use data until his or her marginal benefit is zero (Q1). Because the price paid is equal to the consumer’s willingness to pay, consumer surplus is zero. The provider receives revenues equal to A + B, but also incurs costs equal to B + C, so the producer surplus is A – C.

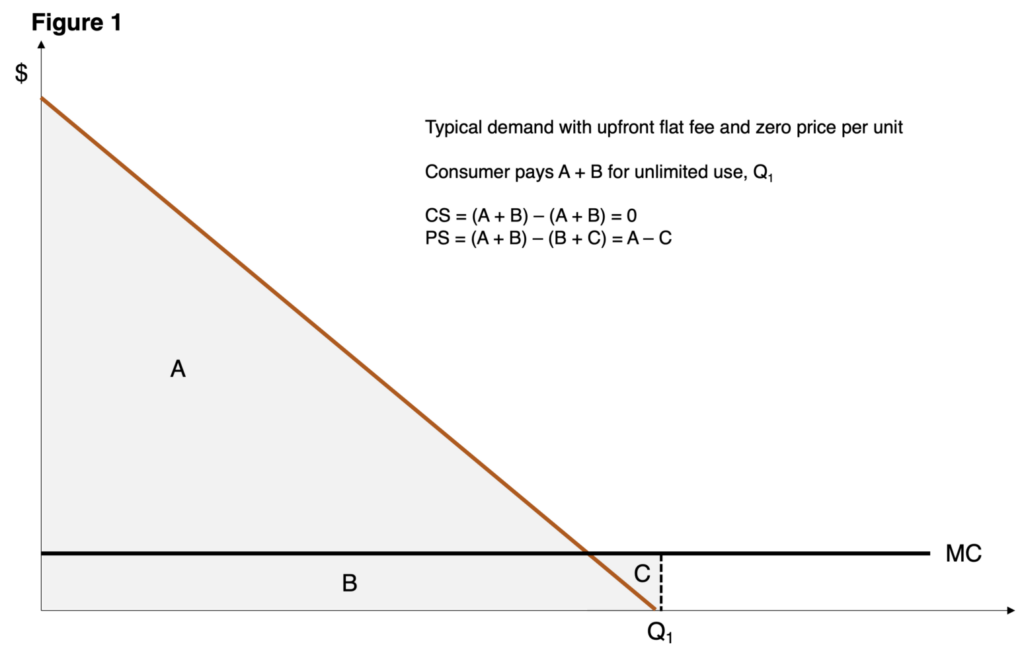

Next, consider a high-demand consumer under the same plan (Figure 2). This consumer will use Q2 amount of data, which is much more than the typical consumer above. She is willing to pay much more for this data (A + B + C + D + E + F), but only pays A + B under her plan, providing a much bigger consumer surplus (C + D + E + F) than for a typical consumer. In contrast, the provider is much worse off with the high-demand consumer under this plan. The provider receives A + B in revenue, but incurs B + C + E + F + G in costs, for a consumer surplus of A – (C + E + F + G), which is substantially less than with a typical consumer.

In a perfect world, the provider would be able to identify which consumers have low, typical, or high demand, and to craft an all-you-can eat plan tailored for each consumer type. But the real world is not so perfect. It may be impossible to accurately identify each type ex ante. More importantly, there are real risks of both adverse selection and moral hazard.

With adverse selection, consumers with large demand would identify themselves as low-demand users to obtain the lower price. With moral hazard, users facing a zero price for data have incentives to find new and additional ways of using data. For example, instead of listening to NPR on their radio, they may have it stream to their smart device. Or instead of watching TV via a cable provider, they “cut the cord” and switch to streaming services. (Note, these are both entirely legitimate practices, which is why, like “junk fees,” “moral hazard” is a pejorative that misrepresents normal practices.)

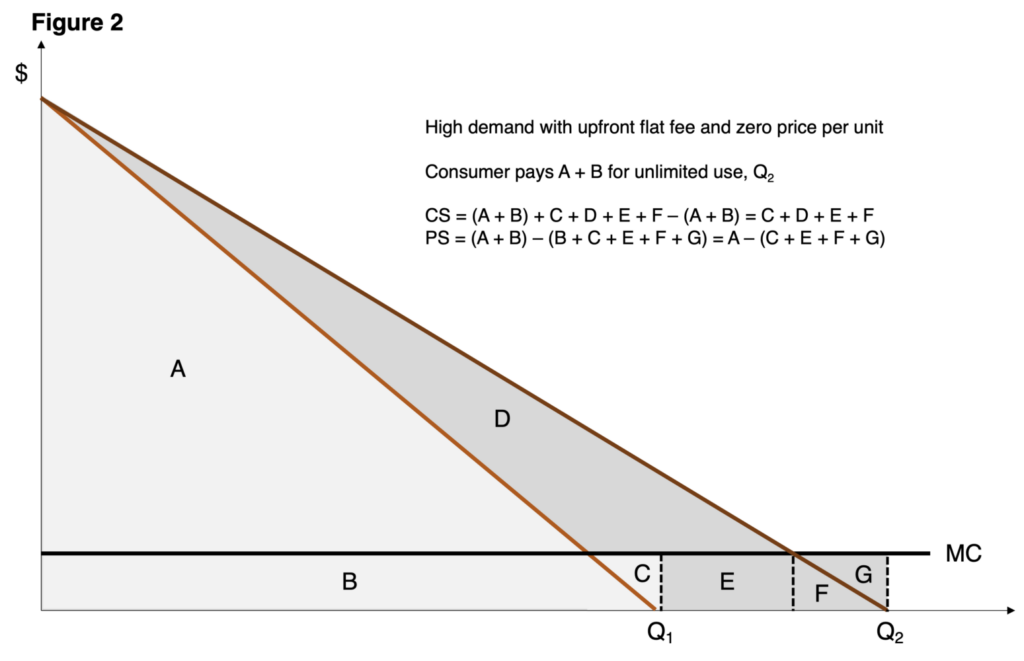

In this imperfect world, providers can implement programs that simultaneously benefit consumers while improving their bottom line. One alternative is usage-based pricing, such as a version of a two-part tariff. Figure 3 illustrates a program that charges an upfront flat fee for unlimited data use up to a specific quantity (Q1). For any data used in excess of that quantity, the consumer is charged a per-unit price equal to the provider’s marginal cost (MC). The consumer will use data until the marginal benefit equals the price charged (Q3, which is more than Q1 and less than Q2). In this case, the consumer would pay the flat fee of A + B, plus a per-unit amount equal to E, which is equal to P x (Q3 – Q1). This amount is less than the consumer is willing to pay, which is equal to A + B + C + D + E. Thus, the consumer surplus is C + D, which is less than under all-can-eat pricing, but more than a typical consumer’s surplus.

The provider receives the flat fee of A + B, plus a per-unit amount equal to E and incurs costs equal to B + C + E, yielding a producer surplus of A – C.

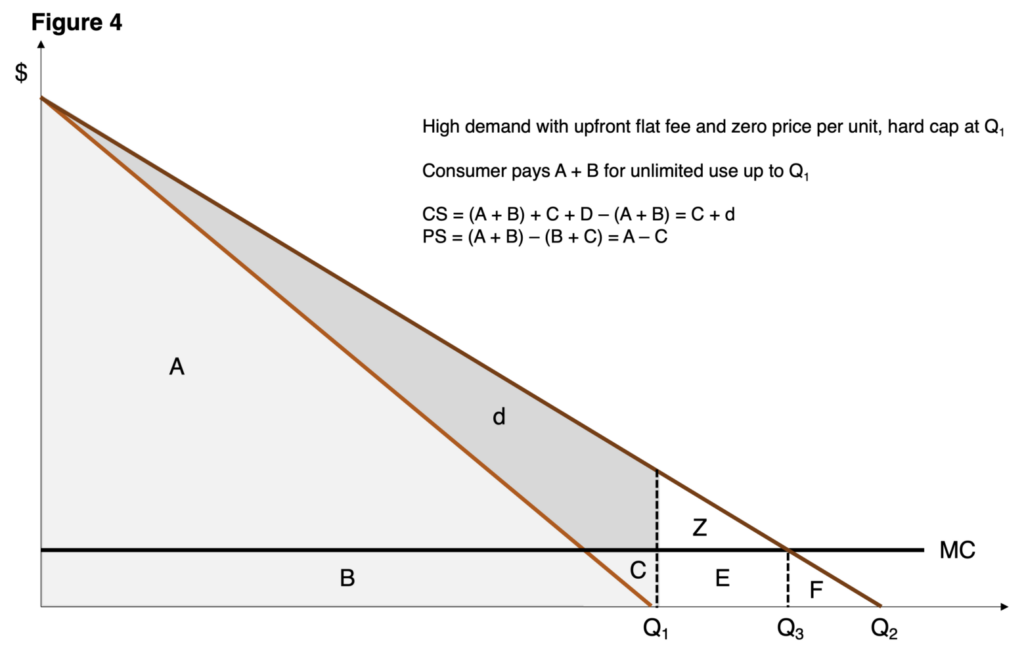

Another alternative that a provider could consider would be a “hard” data cap at specified quantity. Under this policy, the consumer pays an upfront flat fee for unlimited data use up to a specific quantity, Q1, but would not be able to use any data in excess of that amount.

Figure 4 illustrates the result. As with the example of the typical customer in Figure 1, under a “hard” cap, the provider receives A + B in revenue and incurs B + C in costs, yielding a producer surplus of A – C.

The consumer is willing to pay A + B + C + d for this plan, but only pays A + B, providing a consumer surplus of C + d. (Note that I use a lower case “d” in Figure 4 because it is smaller than “D” in Figures 2 & 3—i.e., d = D – Z.)

But here’s where things get interesting. The consumer is willing to pay more for the option to exceed the cap. He or she would be willing to pay up to Z + E to use up to Q3 and willing to pay an additional amount F for unlimited data. And if the consumer made that offer, the provider would accept it, because it would increase the provider’s producer surplus.

Put simply, it is in neither the consumer’s nor the provider’s interest to set a hard data cap. The consumer is willing to pay for more data and the amount the consumer is willing to pay is greater than the additional cost to the provider. That is, not only are hard caps subjectively “bad” for consumers, but they are also bad business, because they leave money on the table. There’s no need to ban hard caps, because the market has already banned them. Consumers don’t want hard caps and providers don’t want to impose them.

The point of this whole hypothetical hootenanny is to demonstrate that usage-based pricing is an elegant solution to profitably accommodate high-use consumers and improve their well-being without affecting other, lower-demand consumers. A program that charges an upfront flat fee for unlimited data use up to a specific quantity, and a per-unit price thereafter, is not in any way a “data cap.” Rather, it is an efficient way to ensure that consumers who want to pay for more data get more data.

Maybe the FCC has already realized this, and that’s why the agency’s data-caps investigation has gone missing. Or maybe the FCC hasn’t realized this, and decided instead that it can shoehorn data-cap regulation in one or more of its other recent expansive regulatory undertakings. Let’s hope it’s the former.