Showing results for: “RPM”

Price-Parity Clauses: The Good, The Bad, and the…Anticompetitive?

Price-parity clauses have, until recently, been little discussed in the academic vertical-price-restraints literature. Their growing importance, however, cannot be ignored, and common misconceptions around their use and implementation need to be addressed. While similar in nature to both resale price maintenance and most-favored-nations clauses, the special vertical relationship between sellers and the platform inherent in ... Price-Parity Clauses: The Good, The Bad, and the…Anticompetitive?

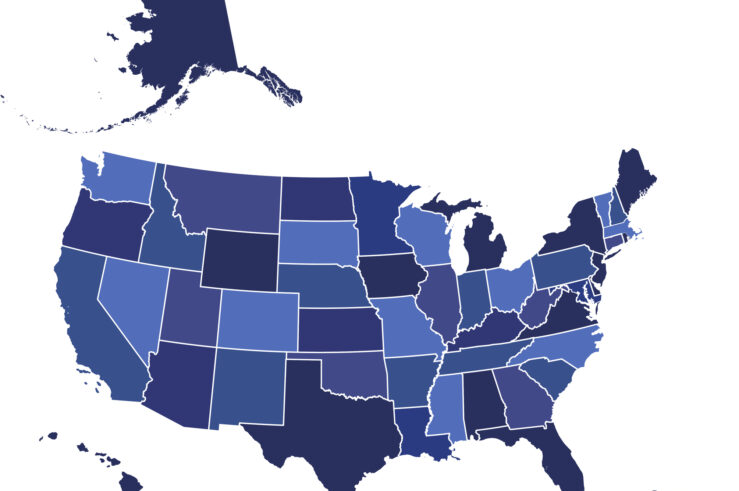

What is the Appropriate Role for State Antitrust Enforcement?

In the U.S. system of dual federal and state sovereigns, a normative analysis reveals principles that could guide state antitrust-enforcement priorities, to promote complementarity in federal and state antitrust policy, and thereby advance consumer welfare. Discussion Positive analysis reveals that state antitrust enforcement is a firmly entrenched feature of American antitrust policy. The U.S. Supreme ... What is the Appropriate Role for State Antitrust Enforcement?

How US and EU Competition Law Differ

U.S. and European competition laws diverge in numerous ways that have important real-world effects. Understanding these differences is vital, particularly as lawmakers in the United States, and the rest of the world, consider adopting a more “European” approach to competition. In broad terms, the European approach is more centralized and political. The European Commission’s Directorate ... How US and EU Competition Law Differ

Global Antitrust Institute Points the Way Toward Sounder Japanese Antitrust Guidelines

The indefatigable (and highly talented) scriveners at the Scalia Law School’s Global Antitrust Institute (GAI) once again have offered a trenchant law and economics assessment that, if followed, would greatly improve a foreign jurisdiction’s competition law guidance. This latest assessment, which is compelling and highly persuasive, is embodied in a May 4 GAI Commentary on ... Global Antitrust Institute Points the Way Toward Sounder Japanese Antitrust Guidelines

ABA Antitrust Section Transition Report: A Respectful Critique

The American Bar Association Antitrust Section’s Presidential Transition Report (“Report”), released on January 24, provides a helpful practitioners’ perspective on the state of federal antitrust and consumer protection enforcement, and propounds a variety of useful recommendations for marginal improvements in agency practices, particularly with respect to improving enforcement transparency and reducing enforcement-related costs. It also ... ABA Antitrust Section Transition Report: A Respectful Critique

Josh Wright and the Limits of Antitrust

Alden Abbott and I recently co-authored an article, forthcoming in the Journal of Competition Law and Economics, in which we examined the degree to which the Supreme Court and the federal enforcement agencies have recognized the inherent limits of antitrust law. We concluded that the Roberts Court has admirably acknowledged those limits and has for ... Josh Wright and the Limits of Antitrust

Commissioner Wright Nails It on Minimum RPM

FTC Commissioner Josh Wright is on a roll. A couple of days before his excellent Ardagh/Saint Gobain dissent addressing merger efficiencies, Wright delivered a terrific speech on minimum resale price maintenance (RPM). The speech, delivered in London to the British Institute of International and Comparative Law, signaled that Wright will seek to correct the FTC’s ... Commissioner Wright Nails It on Minimum RPM

Why the New Evidence on Minimum RPM Doesn’t Justify a Per Se or Quick Look Approach

Mike Sykuta and I recently co-authored a short article discussing the latest evidence on, and proper legal treatment of, minimum resale price maintenance (RPM). Following is a bit about the article (which is available here). Despite the U.S. Supreme Court’s Leegin decision holding that minimum RPM must be evaluated under antitrust’s Rule of Reason, the ... Why the New Evidence on Minimum RPM Doesn’t Justify a Per Se or Quick Look Approach

Some Thoughts on the Spring Meeting: Bummed About RPM, Happy About the FTC’s Future

I’ve spent the last few days in DC at the ABA Antitrust Section’s Spring Meeting. The Spring Meeting is the extravaganza of the year for antitrust lawyers, bringing together leading antitrust practitioners, enforcers, and academics for in-depth discussions about developments in the law. It’s really a terrific event. I was honored this year to have ... Some Thoughts on the Spring Meeting: Bummed About RPM, Happy About the FTC’s Future

The procompetitive story that could undermine the DOJ’s e-books antitrust case against Apple

Did Apple conspire with e-book publishers to raise e-book prices? That’s what DOJ argues in a lawsuit filed yesterday. But does that violate the antitrust laws? Not necessarily—and even if it does, perhaps it shouldn’t. Antitrust’s sole goal is maximizing consumer welfare. While that generally means antitrust regulators should focus on lower prices, the situation is more ... The procompetitive story that could undermine the DOJ’s e-books antitrust case against Apple

The Apple E-Book Kerfuffle Meets Alfred Marshall’s Principles of Economics

From a pure antitrust perspective, the real story behind the DOJ’s Apple e-book investigation is the Division’s deep commitment to the view that Most-Favored-Nation (MFN) clauses are anticompetitive (see also here), no doubt spurred on at least in part by Chief Economist Fiona Scott-Morton’s interesting work on the topic. Of course, there are other important ... The Apple E-Book Kerfuffle Meets Alfred Marshall’s Principles of Economics

AAI’s Antitrust Jury Instruction Project: A good idea in theory, but…

The American Antitrust Institute has announced plans to draft a comprehensive set of jury instructions for antitrust trials. According to AAI president Bert Foer: In Sherman Act Section 1 and Section 2 civil cases, judges tend to gravitate towards the ABA Model Instructions as the gold standard for impartial instructions. … The AAI believes the ABA model ... AAI’s Antitrust Jury Instruction Project: A good idea in theory, but…