Showing archive for: “Antitrust Populism”

The FTC’s UMC Statement Creates a Target for Federal Courts

The Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC) recently released Policy Statement on unfair methods of competition (UMC) has a number of profound problems, which I will detail below. But first, some praise: if the FTC does indeed plan to bring many lawsuits challenging conduct as a standalone UMC (I am dubious it will), then the public ought ... The FTC’s UMC Statement Creates a Target for Federal Courts

Noah Phillips’ Major Contribution to IP-Antitrust Law: The 1-800 Contacts Case

Recently departed Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Commissioner Noah Phillips has been rightly praised as “a powerful voice during his four-year tenure at the FTC, advocating for rational antitrust enforcement and against populist antitrust that derails the fair yet disruptive process of competition.” The FTC will miss his trenchant analysis and collegiality, now that he has ... Noah Phillips’ Major Contribution to IP-Antitrust Law: The <em>1-800 Contacts</em> Case

Political Philosophy, Competition, and Competition Law: The Road to and from Neoliberalism, Part 3

As it has before in its history, liberalism again finds itself at an existential crossroads, with liberally oriented reformers generally falling into two camps: those who seek to subordinate markets to some higher vision of the common good and those for whom the market itself is the common good. The former seek to rein in, ... Political Philosophy, Competition, and Competition Law: The Road to and from Neoliberalism, Part 3

Damn the Economics, Full Speed Ahead!

A White House administration typically announces major new antitrust initiatives in the fall and spring, and this year is no exception. Senior Biden administration officials kicked off the fall season at Fordham Law School (more on that below) by shedding additional light on their plans to expand the accepted scope of antitrust enforcement. Their aggressive ... Damn the Economics, Full Speed Ahead!

The Road to Antitrust’s Least Glorious Hour

Things are heating up in the antitrust world. There is considerable pressure to pass the American Innovation and Choice Online Act (AICOA) before the congressional recess in August—a short legislative window before members of Congress shift their focus almost entirely to campaigning for the mid-term elections. While it would not be impossible to advance the ... The Road to Antitrust’s Least Glorious Hour

Antitrust Populists Don’t Seem to Care About the Poor

Antitrust populists like Biden White House official Tim Wu and author Matt Stoller decry the political influence of large firms. But instead of advocating for policies that tackle this political influence directly, they seek reforms to antitrust enforcement that aim to limit the economic advantages of these firms, believing that will translate into political enfeeblement. ... Antitrust Populists Don’t Seem to Care About the Poor

DOJ’s Threatened Reign of Error: Proposed Criminal-Monopolization Prosecutions

The Biden administration’s antitrust reign of error continues apace. The U.S. Justice Department’s (DOJ) Antitrust Division has indicated in recent months that criminal prosecutions may be forthcoming under Section 2 of the Sherman Antitrust Act, but refuses to provide any guidance regarding enforcement criteria. Earlier this month, Deputy Assistant Attorney General Richard Powers stated that ... DOJ’s Threatened Reign of Error: Proposed Criminal-Monopolization Prosecutions

The FTC UMC Roundup – May 27 Edition

Welcome to the Truth on the Market FTC UMC Roundup for May 27, 2022. This week we have (Hail Mary?) revisions to Sen. Amy Klobuchar’s (D-Minn.) American Innovation and Choice Online Act, initiatives that can’t decide whether they belong in Congress or the Federal Trade Commission, and yet more commentary on inflation and antitrust, along ... The FTC UMC Roundup – May 27 Edition

The Market Challenge to Populist Antitrust

The wave of populist antitrust that has been embraced by regulators and legislators in the United States, United Kingdom, European Union, and other jurisdictions rests on the assumption that currently dominant platforms occupy entrenched positions that only government intervention can dislodge. Following this view, Facebook will forever dominate social networking, Amazon will forever dominate cloud ... The Market Challenge to Populist Antitrust

Concentration Study Further Undermines Narrative that US Competition Has Sharply Declined

A new scholarly study of economic concentration sheds further light on the flawed nature of the Neo-Brandeisian claim that the United States has a serious “competition problem” due to decades of increasing concentration and ineffective antitrust enforcement (see here and here, for example). In a recent article, economist Yueran Ma—assistant professor at the University of ... Concentration Study Further Undermines Narrative that US Competition Has Sharply Declined

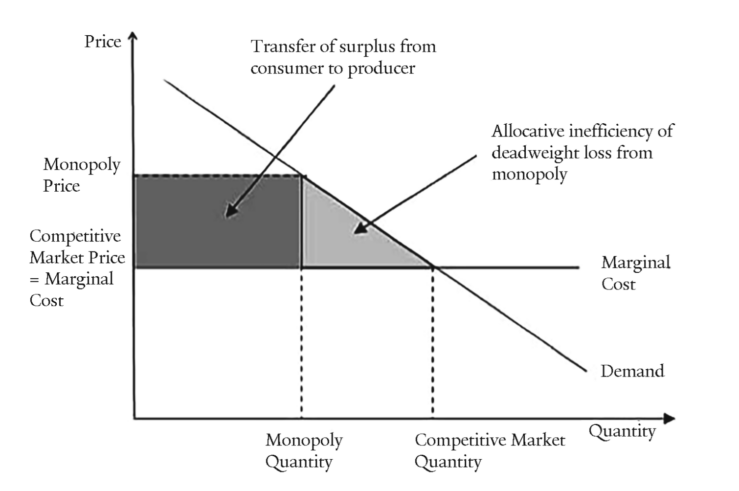

Toward a Dynamic Consumer Welfare Standard for Contemporary U.S. Antitrust Enforcement

For decades, consumer-welfare enhancement appeared to be a key enforcement goal of competition policy (antitrust, in the U.S. usage) in most jurisdictions: The U.S. Supreme Court famously proclaimed American antitrust law to be a “consumer welfare prescription” in Reiter v. Sonotone Corp. (1979). A study by the current adviser to the European Competition Commission’s chief ... Toward a Dynamic Consumer Welfare Standard for Contemporary U.S. Antitrust Enforcement

Does the Market Know Something the FTC Doesn’t?

During the exceptional rise in stock-market valuations from March 2020 to January 2022, both equity investors and antitrust regulators have implicitly agreed that so-called “Big Tech” firms enjoyed unbeatable competitive advantages as gatekeepers with largely unmitigated power over the digital ecosystem. Investors bid up the value of tech stocks to exceptional levels, anticipating no competitive ... Does the Market Know Something the FTC Doesn’t?