Featured

Recently

Published

Reasonable people may disagree about their merits, but digital-competition regulations are now the law of the land in many jurisdictions, including the EU and the UK. Policymakers in those jurisdictions will thus need to successfully navigate heretofore uncharted waters in order to implement these regulations reasonably. In recent comments that we submitted to the UK’s … A Positive Agenda for Digital-Competition Enforcement

While last year’s labor disputes between the Writers Guild of America (WGA) and the Screen Actors Guild (SAG-AFTRA), on the one hand, and Hollywood’s major movie and television studios, on the other, have been settled for months now, lingering questions remain about competitive conditions in the industry. In a recent submission to the California Law … The WGA’s Misguided Fears: Unpacking the Myths of Media Consolidation in the Streaming Era

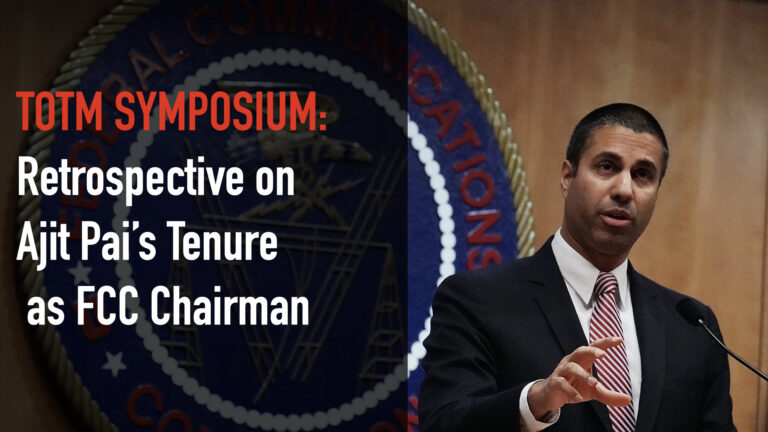

The U.S. Supreme Court’s recent decision in Loper Bright v. Raimondo may have added a new wrinkle to the decades-long fight over whether broadband internet-access services should be classified as “telecommunications services” under Title II of the Communications Act. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has flip-flopped multiple times over the years on this hotly debated … Will the Courts Allow the FCC to Execute One More Title II Flip Flop?