As I noted in my last post, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) announced Sept. 20 that it had filed a complaint:

against the three largest prescription drug benefit managers (PBMs)—Caremark Rx, Express Scripts (ESI), and OptumRx—and their affiliated group purchasing organizations (GPOs) for engaging in anticompetitive and unfair rebating practices that have artificially inflated the list price of insulin drugs, impaired patients’ access to lower list price products, and shifted the cost of high insulin list prices to vulnerable patients.

They later posted a redacted version of the complaint, which is one part competition and two parts consumer protection. The complaint alleges that the defendants violated Section 5 of the FTC Act in three ways.

First, the FTC alleges that, by favoring drug products that provide larger rebates over those with lower list prices (but smaller—or no—rebates), the PBMs violate Section 5’s prohibition of “unfair methods of competition.” This, the complaint alleges, has led to higher prices, at least for certain insulin-drug products, at least for certain patients.

Second, the FTC alleges that, by excluding lower wholesale-acquisition-cost (WAC) insulin products from the formularies they design (or from the preferred tiers of those formularies), the PBMs have restricted patient access to insulin drugs with lower out-of-pocket costs, thereby violating Section 5’s prohibition of “unfair or deceptive acts or practices in or affecting commerce” (UDAP)—the consumer-protection prong of Section 5.

And third, the FTC alleges that the defendant PBMs “unfairly create and implement the system of manufacturer rebates, construct exclusionary formularies that preference high-list priced and highly rebated insulin products, and assist in other aspects of plan design—the combined effect of which shifts the cost of high insulin prices of drugs onto certain insulin patients.” This would, again, constitute a violation of Section 5’s UDAP prohibition. Both UDAP claims are, specifically, unfairness claims, not deception claims.

But how so? Cost shifting to vulnerable patients? No one should be sanguine about high drug prices for those who can least afford them, but the cost-shifting allegation seems dubious, to the point of flunking the “no economic sense” test. But before we attempt to untangle the web of allegations, we might tackle an apparently simpler problem: what is the FTC not alleging?

What the PBMs Are Not Accused Of

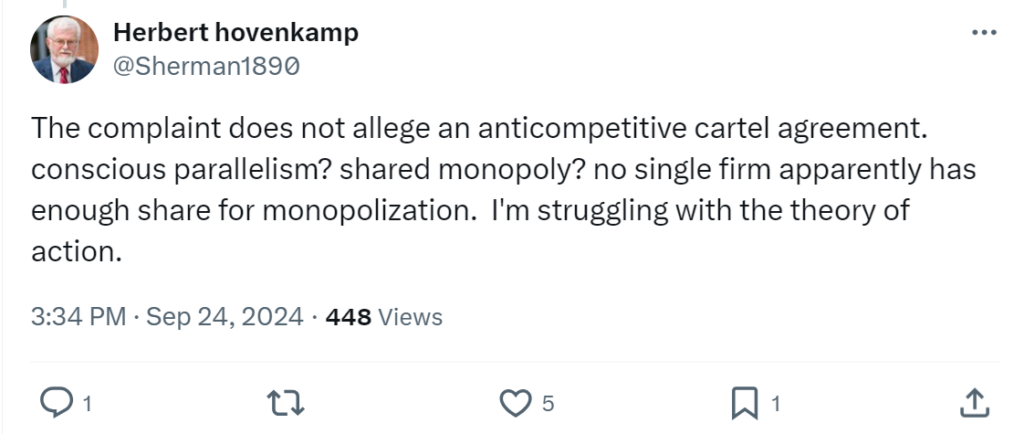

As the University of Pennsylvania’s Herbert Hovenkamp noted on X, the platform formerly known as Twitter:

That’s right. As Hovenkamp observes, there are no allegations of an anticompetitive cartel agreement—e.g., price fixing, a market-allocation agreement, or a group boycott. And while the targets of the FTC’s complaint are, indeed, large firms, none has a market share that would suggest (or even approach) monopoly power in any of the myriad service and product markets in which the PBMs participate.

There’s not even any evident allegation of predatory pricing or, say, anticompetitive foreclosure by one or more of the vertically integrated firms. As far as I can tell, there’s no express allegation that any of the defendants violated either of the two main federal antitrust statutes: the Sherman Antitrust Act or the Clayton Act. Rather, the FTC appears to allege “standalone” violations of Section 5 of the FTC Act.

There can be no doubt that drug expenditures are considerable, or that some pharmaceutical and biological drugs are extremely expensive. A 2022 Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report observed that, “[n]ationwide per capita use of prescription drugs has increased in recent years,” and that branded pharmaceuticals may be especially expensive, with branded prices having increased on average.

At the same time, some of the increase is due to an aging population. Moreover, CBO noted that:

After decades of increases, per capita spending on prescription drugs began to level off in real terms … in the mid-2000s. Since that time, such spending has fallen as a percentage of total spending on health care services and supplies. That slower growth in spending is associated with the growing availability of generic drugs, which tend to have much lower prices than their brand-name counterparts.

In addition, the lion’s share of prescriptions has been shifting to lower-cost generic drugs. CBO observes, for example, that the generic share of prescriptions “increased from 75 percent in 2009 to 90 percent in 2018” nationwide, and that “average prices for generic drugs have fallen in recent years.” Overall, according to CBO:

The share of spending on prescription drugs that insurers cover has increased substantially: In 1990, consumers paid 57 percent of their prescription drug costs out of pocket, on average. By 2009, that share had fallen to 20 percent; it fell further, to 15 percent, in 2018.

So, whatever the PBMs’ influence is on drug selection, a large (and rising) majority of prescriptions are filled with lower-priced generic-drug products, and the share of prescription-drug costs that consumers cover out of pocket has been falling. That’s on average, across the pharmacopeia, but perhaps it’s different for the heart of the FTC’s complaint, which is focused on insulin-drug products?

Before we ask about the impact of PBM conduct on insulin prices, we might ask, very simply, what the complaint tells us, or alleges, about insulin prices. That’s not so clear. We are told that, “[d]espite recent list price decreases on some insulin products, the list prices of other insulin products remain high.” We’re also told that many consumers pay prices out of pocket that are “based on” those list prices. And, indisputably of policy concern, we’re told that many patients report rationing their insulin.

That’s certainly a matter of legitimate health-policy concern, whether or not it’s a competition matter, and whether or not it is caused by the PBM practices at-issue. What the FTC complaint does not tell us is whether the actual net price of insulin (or equivalent insulin-drug products)—not the WAC or the list price, but the net price paid—has increased for most consumers. Nor does it tell us whether those consumers are health-plan sponsors or the patients who are the plan beneficiaries. Have real net prices increased for most consumers? Have real mean average prices increased? Median or modal prices?

Recall the review of PBMs that I offered on Friday. The FTC’s own 2005 PBM report found that, on average, mail-order prices from the large PBMs were lower than retail prices for the same drug products and same-sized prescriptions, and that average mail-order prices at integrated (retailer-owned) PBMs were lower than retail prices for the same drug products and same-sized prescriptions. That is, the FTC concluded that, in general, for the 2002-03 period studied, PBM ownership of mail-order pharmacies, and the use of mail order, did not disadvantage plan sponsors but instead provided cost savings, on net.

That was then and this is now, but were any of the specific findings of the 2005 report repudiated by the FTC’s 2024 “interim staff report”? Not really, despite throwing much rhetorical shade on the earlier report. And while the 2005 report can still be found on the FTC website, it is overlain with a bright yellow warning label that it is there “for reference only.” The commission also issued a statement cautioning the public and policymakers against relying on certain FTC materials, which it said “should not be assumed to reflect current market conditions.”

Indeed, current leadership at the FTC has added “warning labels” to various commission and staff advocacies on PBM-related issues, much like the label attached to the 2005 report. For example, we are warned about the FTC’s 2014 comments to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), which noted:

Based on FTC staff’s experience in this area, as well as our review of empirical studies of preferred provider contracting and any willing provider and FOC laws, there are two clear and consistent conclusions in the literature:

- Selective contracting with pharmacies and other health care providers can lower prices paid by plans and their beneficiaries; and

- Any willing provider and FOC laws tend to raise prices or spending because they impair the ability of Part D plan providers to engage in selective contracting.

That’s of interest because, among other things, the FTC’s prayer for relief in its new complaint would impose novel—and somewhat open-ended—restrictions on both formulary design and plan design. And warning labels aside, there are no concrete findings in the 2024 report that are inconsistent with those “clear and consistent” conclusions.

As I described in more detail here (and see a thorough dissenting statement from Commissioner Melissa Holyoak on the decision to issue the 2024 report), the interim staff report was sorely lacking in systematic analysis of the data collected in the commission’s 6(b) study, and in findings about drug prices that could be tied to PBM practices.

What’s missing from the 2024 report matters, because it seems to be missing from the FTC’s complaint, as well. If we want to know whether PBMs have, in violation of the antitrust laws, caused harm to competition somewhere along the chain of manufacturing and distribution—somewhere, in some market—we’d at least like to know whether and how prescription-drug development, manufacturing, distribution, or sales have been harmed. Has output declined? Have prices increased, on net, in real dollars? Is the FTC alleging, at a minimum, that actual retail out-of-pocket prices have increased for the typical consumer?

We cannot find the answers in the FTC’s 2024 report. And besides bald (and somewhat hedged) allegations, we cannot find them in the FTC’s complaint either.

The complaint tells us, e.g., that:

Despite the growing rebates, the average net price of Humalog (after rebates and fees) continued to rise following the PBM Respondents’ introduction of their exclusionary formularies—due to ever-escalating list prices. It took several years, around 2014-2015, for the net price of Humalog and other insulin products to begin to decline.

So, net prices for one insulin product (Humalog) rose for several years as rebates grew, but then, “around 2014-2015, the net price of Humalog and other insulin products began to decline.” Leaving aside the key question of cause and effect, where are net adjusted prices now, at least on average, and how have they tracked (or failed to track) the PBM practices at-issue? For Humalog? For all insulin products?

The FTC has a story, if not concrete findings: PBMs employ formulary designs and favor rebate practices that create incentives for drug manufacturers to set high list prices. While those WAC and list prices are not the prices paid—not by health plans, nor by the large majority of patients—they do have some bearing on the actual prices paid by some consumers, not least because some patients are uninsured or underinsured, and because many health-plan beneficiaries elect lower-cost (and lower-coverage) plans.

But the complaint acknowledges that high list prices are diminished, at the back end, via high rebate payments, lowering the net cost to the recipient of the rebate. And that recipient is, for the most part, the plan sponsor, not the PBM. Those savings may be passed along to plan beneficiaries, whether in the form of lower copayments, lower plan costs, or better coverage. And, indeed, the complaint acknowledges that “[b]y retaining the rebates, the commercial payers may lower their own overall costs of health care benefits. This may in turn partially reduce the amount that employers have to contribute in premiums.”

Note, too, that the FTC does not strictly confine its complaint to insulin-drug products, but without alleging anything specific. Again, we’d like to know about specific lines of commerce and actual net effects, and the reference to the “other critical drugs” doesn’t tell us very much at all.

The Current FTC’s View of Section 5

Part of what’s interesting here is the current commission’s view of Section 5 and, specifically, of the UMC prong of Section 5. As Geoff Manne and I wrote in 2023, over the course of about 100 years:

An understanding emerged that the FTC’s UMC authority reached somewhat beyond the Sherman Act, but was still tethered to the central antitrust concepts of the consumer welfare standard and the “rule of reason,” both of which offer courts a means to evaluate the legality of market behavior in terms of its likely harms and benefits.

So, for example, whereas a violation of Section 1 of the Sherman Act required an actual agreement among competitors, there was a consensus that an “invitation to collude” could suffice for Section 5—basically, it would be an attempt to commit a per se violation of the Sherman Act without any countervailing procompetitive purpose.

Over the dissent of then-Commissioner Christine Wilson, a three-member majority of the new FTC issued a new Section 5 policy statement in November 2022, to some fanfare and considerably greater confusion and consternation. As Gus Hurwitz and I noted at the time, the new statement announced the commission’s intent to “target a much broader range of conduct than it has in the past, as it untethers ‘unfair methods of competition’ from, inter alia, consumer welfare, the rule of reason, and actual or likely harm to competition.”

Whether the 2022 policy statement contemplates prohibiting the PBM conduct at-issue is unclear. It’s a broad and malleable kitchen-sink sort of statement, one with no limiting principles in evidence, so it’s hard to say that it does not. Or that it demands it. In any case, a policy statement by a three-member majority of FTC commissioners is not a statute, regulation, or judicial decision. Whether the statement might come to find purchase in the courts is anyone’s guess. I was skeptical before the U.S. Supreme Court repudiated the Chevron doctrine in Loper Bright. And Loper Bright did not make me credulous.

Not incidentally, in 2019, at the behest of Congress, the FTC itself issued its “Report on Standalone Section 5 to Address High Pharmaceutical Drug and Biologic Prices.” In it, the FTC noted that:

Were the Commission to invoke its standalone Section 5 authority to challenge high drug prices, and were the Commission to pursue theories not tied to harm from collusive or exclusionary conduct recognized under Section 1 or Section 2 of the Sherman Act, courts likely would be hostile to the attempted expansion of liability.

That’s all about the question of whether there’s been a UMC violation. But what about UDAP? That seems very much a matter of “same same, but different.” On the one hand, while the proper application of Section 5’s UDAP prohibition is not always straightforward, it is less controversial. On the other hand, there’s that pesky limitation on the FTC’s UDAP authority in the plain language of Section 5(n), which stipulates that:

The Commission shall have no authority under this section . . . to declare unlawful an act or practice on the grounds that such act or practice is unfair unless the act or practice causes or is likely to cause substantial injury to consumers which is not reasonably avoidable by consumers themselves and not outweighed by countervailing benefits to consumers or to competition.

The FTC’s PBM complaint alleges that the “[r]espondents have created an opaque drug pricing and reimbursement system, which benefits them but which deliberately obscures the full scope of harm and financial cost from insurers and patients.” But the complaint’s UDAP counts do not allege unlawful deception; they only allege unfairness. Given the limitations of 5(n), all of the above-raised questions about the FTC’s competition complaint are in full force when we think about an unfairness complaint.

Who Is Harmed? Who Benefits?

If some end-consumers (patients) are harmed because, say, (a) their health-plan sponsor seeks (or designs) a relatively narrow formulary or (b) the consumers themselves select more limited (perhaps less expensive) prescription-drug coverage from among various plans offered by the sponsor (employer, union, etc.), then is the harm a “substantial injury to consumers [by the PBMs] which is not reasonably avoidable by [the] consumers themselves”? And if some consumers are disadvantaged, while many more benefit, does that establish the requisite harm?

If downstream benefits flow to the health plans and plan sponsors that engage the PBMs—with some (many) benefits flowing to many plan beneficiaries, such that average out-of-pocket costs are lower, not higher, and such that output is increased, not reduced—is that not a countervailing benefit to “consumers or competition”? The complaint says that there are no such countervailing benefits. But simply saying so falls well short of proving it. And as we’ve seen, other sources suggest otherwise.

What of other links in the chain of distribution? The FTC says that PBMs “use their size, scale, and position in the drug transaction chain to pressure manufacturers to secure favorable formulary placement by prioritizing the size of the rebates” and that they “push manufacturers to achieve a lower net price with the highest rebates and fees.” (emphasis in original).

But how much “pressure” or “push” is that across markets? The large PBMs are, indeed, large, but none is a monopolist. The interim staff report, focusing on but one of the many varied PBM services to highlight market concentration, notes that:

[T]he top three PBMs—CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, and OptumRx … (together, the “Big 3”)—manage 79 percent of prescription drug claims for approximately 270 million people. With the next three largest PBMs—Humana Pharmacy Solutions, MedImpact, and Prime—the six largest PBMs (together, the “Big 6”) now manage 94 percent of prescription drug claims in the United States.

Setting aside that claims management may be the oldest and broadest of PBM services, 79% service-market share is divided among three large firms. There’s no allegation that any single firm has as much as a third of the market for any of the many PBM services, including claims management. There is no allegation that those three firms (or any subset of the “big six”) collude on formulary design (which is not fixed, even for any one large PBM), wholesale prices, or rebates. And, of course, the next three largest PBMs are not trivial entities at all. How much can any one of the “big three” or “big six” PBMs push large manufacturers?

The FTC argues that patients “have little ability to avoid the substantial injury incurred,” because, among other things, “[s]witching plans would be ineffective as many plans are similarly affected . . . [and] [e]ven if it were effective, patients cannot easily switch formularies, because the PBMs and GPOs do not contract directly with patients. Rather, patients must go through an insurer—often their employer—to benefit from the rates negotiated by the PBMs and GPOs.”

Perhaps, but plan designs—including formulary designs offered by the largest PBMs—are diverse and are negotiated with (and sometimes custom-designed at the behest of) plan sponsors, such as employers, labor unions, etc. Do large employers, like the federal and state governments or, e.g., large firms such as Walmart, Amazon, Home Depot, or Target, or large unions such as the AFL-CIO (12.5 million members), the National Education Association (over 3 million members), or the Teamsters (about 1.4 million members) have no bargaining power or access to expert consultants outside the large PBMs?

What about large insurers that are not integrated with the largest PBMs, such as Kaiser Permanente and the largest Blue Cross/Blue Shield plans? Insurance benefits are subject to considerable state regulation, and a 2023 report by the American Medical Association notes that most health insurers’ enrollments’ are concentrated geographically.

So, for example, the state of Michigan is the 11th largest market and BCBS of Michigan “has a 67% market share there.” Not incidentally, it also notes that “Health Care Service Corporation (BCBS) is in five states, including two of the five largest state-level markets and the third, fourth and sixth largest MSA-level markets in the U.S.” Are BCBS of Michigan or similar locally dominant health insurers likewise pawns of the PBMs?

At the beginning of the chain of distribution, the FTC’s complaint notes that “[f]our companies manufacture insulin for sale in the U.S.” and that manufacturers set the list prices for insulin. That is, the large PBMs negotiate with large manufacturers in a concentrated market for insulin manufacture, just as they negotiate with large plans and plan sponsors (among others) in what may be concentrated regional or local insurer markets.

Moving beyond insulin, we may find branded drug products for which there are few or no close substitutes (it’s hard to attribute much leverage to the PBMs in those cases) to those for which there are many (hence, the 90% of U.S. prescriptions filled by low-priced generic-drug products).

The point of this is not to suggest that other parties are violating the FTC Act or any other U.S. laws. Rather, even beyond the significant roles played by Congress and the states, both via federal and state programs and via regulation, the FTC is at least right that the supply, distribution, and pricing of prescription drugs is an exceedingly complex matter. Indeed, this may go some way to explaining the growth of PBMs and PBM services, notwithstanding the sophistication and leverage of many PBM clients.

Conclusion

I keep coming back to the FTC’s 2005 PBM report and other pertinent research. What is the net effect, on average, of (a) any given form of PBM conduct or (b) any given PBM’s conduct on real drug prices and availability? On net and on average, it seems beneficial. Those averages may obscure much of importance, but parsing what’s truly problematic—and a violation of the law—is the job of the enforcer and its complaint.

And given copious research on relevant conduct by academics, FTC staff, and other government agencies, one must wonder about the extent to which the FTC contemplates regulating plan design, formulary design, or pricing. Do we know what they plan to do? And is there any systematic research suggesting that such intervention will be beneficial? If so, one would like to see it. Just as one would like to see the FTC publish a serious, economically grounded report on PBMs. Like the 2005 report.