The Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC) proposed digital-discrimination rules hit the streets earlier this month and, as we say at Hootenanny Central, they’re a real humdinger.

It looks like the National Telecommunications and Information Agency (NTIA) got most of their wishlist incorporated into the proposed rules. We’ve got disparate impact and a wide-open door for future rate regulation.

Here’s the tl;dr version of the new rules. More details at the end of this post.

- The rules are intended to foster equal access and to prevent discrimination in access to broadband internet service;

- Equal access means equal opportunity for consumers to subscribe to broadband service;

- Consumers include both potential subscribers and existing subscribers;

- Broadband service includes every element of a consumer’s broadband-internet experience, including speeds, data caps, pricing and discounts;

- The rules prohibit intentional discrimination, as well as policies and practices that can be demonstrated to result in a disparate impact on protected groups of consumers;

- In addition to typical broadband providers, the rules broadly apply to “entities outside the communications industry” that “provide services that facilitate and affect consumer access to broadband,” which may include municipalities and property owners.

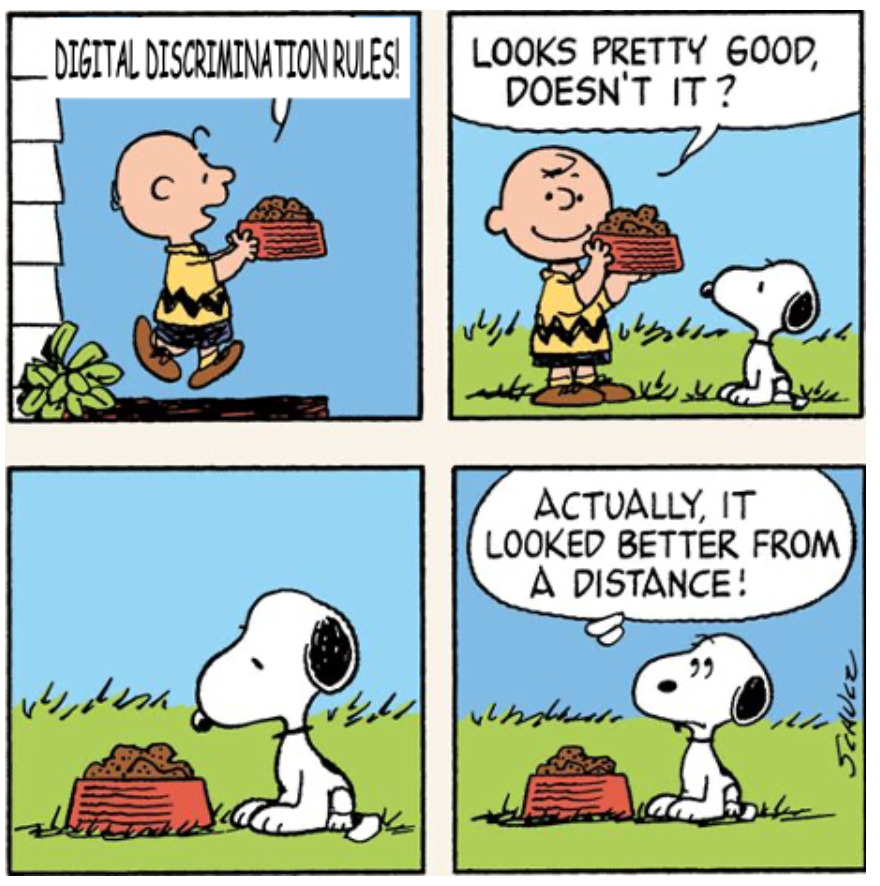

From a distance, these rules seem sensible. They cover many of the most obvious allegations of digital discrimination, like “digital redlining” or providing different speeds for the same price within a city.

But on closer inspection, the rules are overly broad when it comes to who is covered and what policies and practices could be subject to digital-discrimination claims. As written, the proposed rules pooh-pooh intentional discrimination as something that is nearly nonexistent: “By commenters’ own admission, there is little to no evidence of intentional digital discrimination of access.” (¶ 56). Thus, the FCC argues, “most of the gaps in access to broadband internet service in our country … stem from policies and practices that are neutral on their face” (¶ 42) and invite scrutiny under a disparate-impact approach.

But many policies and practices are explicitly discriminatory—especially those based on income–except that their effect is to benefit the poor. For example, Xfinity’s Internet Essentials program for low-income households could run afoul of the rules’ prohibition on income-based discrimination.

Local government efforts to expand or preserve broadband subscriptions could also be subject to the new rules. For example, in 2021, the City of Portland, Oregon handed out 8,000 debit cards preloaded with $364 each to cover the cost of internet access for one year. Low-income households and people of color were given priority in distribution of the cards. That program would be a clear violation of the FCC’s proposed rules. The city would be a covered entity, because it “facilitates the provision of broadband internet access or affects consumer access to broadband internet access.” The prioritization is explicit: intentional discrimination based on race and income level.

In Tennessee, Hamilton County Schools’ EdConnect program offers free high-speed internet access to eligible students, where eligibility is based on income level—i.e., students who receive free or reduced-cost lunch, attend any school where every student receives free or reduced-cost lunch, or whose family participates in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) or other economic-assistance programs. Both the school district and the nonprofit that runs the program would also be covered entities. The fact that the price (free) is available only to those of a certain income level is explicit, intentional discrimination.

Each of these programs were intended to increase broadband adoption. But how will the FCC handle well-intentioned programs that are intentionally discriminatory?

The FCC says it will take a case-by-case approach to discrimination claims. But if it determines that some discrimination is OK and some discrimination isn’t, then we’ll end up with a mishmash of decisions that offer no useful guidance to providers.

Economist Michael Munger often says: “Never make a sword you don’t want to see wielded by your worst enemy right after the next election.” It’s looking like the FCC is now forging such a sword with its digital-discrimination rules. By taking such an expansive approach to the rules, the agency is fostering a future FCC with the tools to use those same rules to eviscerate many well-intentioned and effective programs, policies, and practices to expand broadband access and adoption.

If you’re a tl;dr person, you can stop here. If you’re a details person, here come those details.

Digital Discrimination Defined

Paragraph 31 (emphasis added):

Section 60506(a) first declares “the policy of the United States that, insofar as technically and economically feasible … subscribers should benefit from equal access to broadband internet access service within the service area of a provider of such service … [and that] the Commission should take steps to ensure that all people of the United States benefit from equal access to broadband internet access service.” Section 60506(b) then directs the Commission to “adopt final rules to facilitate equal access to broadband internet access service, taking into account the issues of technical and economic feasibility presented by that objective,” and mandates that those rules include “preventing digital discrimination of access based on income level, race, ethnicity, color, religion, or national origin” and “identifying necessary steps for the Commission[] to take to eliminate” such digital discrimination of access.

Paragraph 32 (emphasis added):

The “equal access” that we are to ensure and facilitate is defined in subsection (a)(2) as “the equal opportunity to subscribe to an offered service that provides comparable speeds, capacities, latency, and other quality of service metrics in a given area, for comparable terms and conditions.”

Disparate Impact and Intentional Discrimination

Paragraph 33 (emphasis added):

Policies or practices, not justified by genuine issues of technical or economic feasibility, that

(1) differentially impact consumers’ access to broadband internet access service based on their income level, race, ethnicity, color, religion or national origin or

(2) are intended to have such differential impact.

Paragraph 38 (emphasis added, citations omitted):

Based on the record before us, we do not expect to encounter many instances of intentional discrimination with respect to deployment and network upgrades, as there is little or no evidence in the legislative history of section 60506 or the record of this proceeding indicating that intentional discrimination by industry participants based on the listed characteristics substantially contributes to disparities in access to broadband internet service across the Nation.

Paragraph 56:

By commenters’ own admission, there is little to no evidence of intentional digital discrimination of access.

Paragraph 42 (emphasis added, citations omitted):

Equal access can be denied by policies and practices having discriminatory effects even where no discriminatory motive is present, and it is our considered view that most of the gaps in access to broadband internet service in our country … stem from policies and practices that are neutral on their face, rather than from intentionally discriminatory conduct on the part of covered entities and other industry participants.

Paragraph 46 (emphasis added, citations omitted):

We find that by defining the goals of section 60506 in terms of “equal access” and “equal opportunity,” especially in light of the 52-year history of disparate impact analysis in civil rights law, Congress expressed its intention that the Commission’s implementing regulations address business conduct having the effect of denying designated groups of consumers the equal opportunity to subscribe to an offered broadband service, regardless of the motivation for such actions.

Limits to Disparate-Impact Analysis

Paragraph 49:

[A]ny determination of differential impact that relies on observed disparity must point to a specific policy or practice that is causing the disparity.

Paragraph 50:

[T]he rules will give covered entities an opportunity to present justifications for discriminatory policies and practices. Section 60506 sets out such limitation by requiring that our rules facilitate equal access while taking into account “issues of technical and economic feasibility.

Entities Covered by the Rules

Paragraph 85:

Covered entities include, but are not limited to:

- Broadband providers;

- Contractors retained by, or entities working through partnership agreements or other business arrangements with, broadband internet access service providers;

Entities facilitating or involved in the provision of broadband internet access service;- Entities maintaining and upgrading network infrastructure; and

- Entities that otherwise affect consumer access to broadband internet access service.

Paragraph 87:

Thus, to the extent that entities outside the communications industry provide services that facilitate and affect consumer access to broadband, they may be in violation of our rules if their policies and practices impede equal access to broadband internet access service as specified in the rules.

Paragraph 87 also mentions “a landlord restricting broadband options within a building even if multiple providers are available” may be subject to the rules.

Paragraph 88 (emphasis added):

Lastly, we acknowledge that commenters disagree on whether to include infrastructure owners and local governments within the scope of our rules, but we decline to expressly carve out specified entities from the scope of coverage at this time. … Additionally, Local Governments request that we not categorize local governments as “covered entities” based on their roles as right-of-way managers or franchise regulators. While there may be tension in the record as to the role these entities play, our rule is clear that any entity that meaningfully affects access to broadband internet service is subject to our digital discrimination of access rules.

Consumers, Not Just Subscribers

Paragraph 89 (emphasis in original, citations omitted):

The definition of digital discrimination of access adopted today includes “policies and practices … that differentially impact consumers’ access to broadband internet access service … or are intended to have such differential impact.” We today define “consumers” in this context to mean both current and potential subscribers, which includes individual persons, groups of persons, individual organizations, and groups of organizations having the capacity to subscribe to and receive broadband internet access service. We define “subscriber” as a current recipient of broadband internet access service as defined in section 8.1(b) of the Commission’s rules.

Rate Regulation

Paragraph 100 (emphasis added):

The rules we adopt today apply to any lack of comparability in service quality, as indicated by the metrics specifically listed in the statutory definition of “equal access” as well as any “other quality of service metrics in a given area,” and to any lack of comparability in terms and conditions of service, including but not limited to price. We find this scope of coverage to be consistent with section 60506’s statutory text and necessary to effectuate its purpose.

Paragraph 105 (emphasis added):

Finally, regarding the inclusion of pricing within the scope of our rules, we find that the statutory language encompasses discriminatory pricing. We emphasize that the rules we adopt today do not set rates for broadband internet access service and are not an attempt to institute rate regulation.

Paragraph 106:

Verizon argues that our rules can only address policies and practices concerning the consumer’s ability to sign up for service (i.e., contract formation), but cannot address whether the service is actually rendered on equal terms (i.e., contract performance). We disagree with this interpretation. We acknowledge that the definition of “equal access” in section 60506(a) refers to the “equal opportunity to subscribe to an offered service ….” But we find the word “subscribe” in this context means more than simply signing up for service. It refers, instead, to the ability to receive and effectively utilize the service so as to allow full participation in the social, educational, political and economic life of our Nation.