“Just when I thought I was out, they pull me back in!” says Al Pacino’s character, Michael Corleone, in Godfather III. That’s how Facebook and Google must feel about S. 673, the Journalism Competition and Preservation Act (JCPA).

Gus Hurwitz called the bill dead in September. Then it passed the Senate Judiciary Committee. Now, there are some reports that suggest it could be added to the obviously unrelated National Defense Authorization Act (it should be noted that the JCPA was not included in the version of NDAA introduced in the U.S. House).

For an overview of the bill and its flaws, see Dirk Auer and Ben Sperry’s tl;dr. The JCPA would force “covered” online platforms like Facebook and Google to pay for journalism accessed through those platforms. When a user posts a news article on Facebook, which then drives traffic to the news source, Facebook would have to pay. I won’t get paid for links to my banger cat videos, no matter how popular they are, since I’m not a qualifying publication.

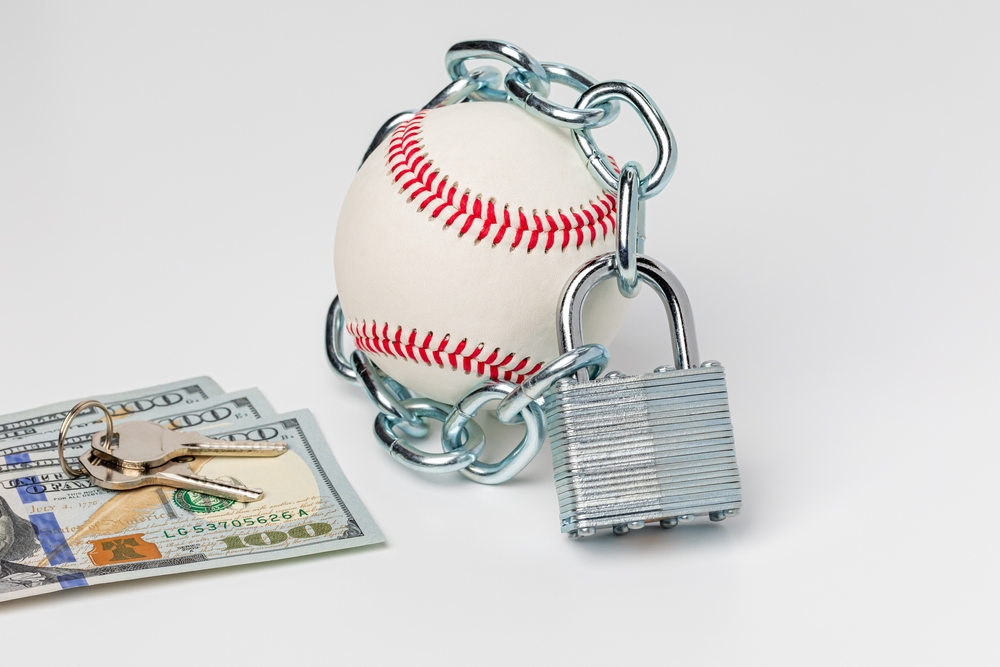

I’m going to focus on one aspect of the bill: the use of “final offer arbitration” (FOA) to settle disputes between platforms and news outlets. FOA is sometimes called “baseball arbitration” because it is used for contract disputes in Major League Baseball. This form of arbitration has also been implemented in other jurisdictions to govern similar disputes, notably by the Australian ACCC.

Before getting to the more complicated case, let’s start simple.

Scenario #1: I’m a corn farmer. You’re a granary who buys corn. We’re both invested in this industry, so let’s assume we can’t abandon negotiations in the near term and need to find an agreeable price. In a market, people make offers. Prices vary each year. I decide when to sell my corn based on prevailing market prices and my beliefs about when they will change.

Scenario #2: A government agency comes in (without either of us asking for it) and says the price of corn this year is $6 per bushel. In conventional economics, we call that a price regulation. Unlike a market price, where both sides sign off, regulated prices do not enjoy mutual agreement by the parties to the transaction.

Scenario #3: Instead of a price imposed independently by regulation, one of the parties (say, the corn farmer) may seek a higher price of $6.50 per bushel and petition the government. The government agrees and the price is set at $6.50. We would still call that price regulation, but the outcome reflects what at least one of the parties wanted and some may argue that it helps “the little guy.” (Let’s forget that many modern farms are large operations with bargaining power. In our head and in this story, the corn farmer is still a struggling mom-and-pop about to lose their house.)

Scenario #4: Instead of listening only to the corn farmer, both the farmer and the granary tell the government their “final offer” and the government picks one of those offers, not somewhere in between. The parties don’t give any reasons—just the offer. This is called “final offer arbitration” (FOA).

As an arbitration mechanism, FOA makes sense, even if it is not always ideal. It avoids some of the issues that can attend “splitting the difference” between the parties.

While it is better than other systems, it is still a price regulation. In the JCPA’s case, it would not be imposed immediately; the two parties can negotiate on their own (in the shadow of the imposed FOA). And the actual arbitration decision wouldn’t technically be made by the government, but by a third party. Fine. But ultimately, after stripping away the veneer, this is all just an elaborate mechanism built atop the threat of the government choosing the price in the market.

I call that price regulation. The losing party does not like the agreement and never agreed to the overall mechanism. Unlike in voluntary markets, at least one of the parties does not agree with the final price. Moreover, neither party explicitly chose the arbitration mechanism.

The JCPA’s FOA system is not precisely like the baseball situation. In baseball, there is choice on the front-end. Players and owners agree to the system. In baseball, there is also choice after negotiations start. Players can still strike; owners can enact a lockout. Under the JCPA, the platforms must carry the content. They cannot walk away.

I’m an economist, not a philosopher. The problem with force is not that it is unpleasant. Instead, the issue is that force distorts the knowledge conveyed through market transactions. That distortion prevents resources from moving to their highest valued use.

How do we know the apple is more valuable to Armen than it is to Ben? In a market, “we” don’t need to know. No benevolent outsider needs to pick the “right” price for other people. In most free markets, a seller posts a price. Buyers just need to decide whether they value it more than that price. Armen voluntarily pays Ben for the apple and Ben accepts the transaction. That’s how we know the apple is in the right hands.

Often, transactions are about more than just price. Sometimes there may be haggling and bargaining, especially on bigger purchases. Workers negotiate wages, even when the ad stipulates a specific wage. Home buyers make offers and negotiate.

But this just kicks up the issue of information to one more level. Negotiating is costly. That is why sometimes, in anticipation of costly disputes down the road, the two sides voluntarily agree to use an arbitration mechanism. MLB players agree to baseball arbitration. That is the two sides revealing that they believe the costs of disputes outweigh the losses from arbitration.

Again, each side conveys their beliefs and values by agreeing to the arbitration mechanism. Each step in the negotiation process allows the parties to convey the relevant information. No outsider needs to know “the right” answer.For a choice to convey information about relative values, it needs to be freely chosen.

At an abstract level, any trade has two parts. First, people agree to the mechanism, which determines who makes what kinds of offers. At the grocery store, the mechanism is “seller picks the price and buyer picks the quantity.” For buying and selling a house, the mechanism is “seller posts price, buyer can offer above or below and request other conditions.” After both parties agree to the terms, the mechanism plays out and both sides make or accept offers within the mechanism.

We need choice on both aspects for the price to capture each side’s private information.

For example, suppose someone comes up to you with a gun and says “give me your wallet or your watch. Your choice.” When you “choose” your watch, we don’t actually call that a choice, since you didn’t pick the mechanism. We have no way of knowing whether the watch means more to you or to the guy with the gun.

When the JCPA forces Facebook to negotiate with a local news website and Facebook offers to pay a penny per visit, it conveys no information about the relative value that the news website is generating for Facebook. Facebook may just be worried that the website will ask for two pennies and the arbitrator will pick the higher price. It is equally plausible that in a world without transaction costs, the news would pay Facebook, since Facebook sends traffic to them. Is there any chance the arbitrator will pick Facebook’s offer if it asks to be paid? Of course not, so Facebook will never make that offer.

For sure, things are imposed on us all the time. That is the nature of regulation. Energy prices are regulated. I’m not against regulation. But we should defend that use of force on its own terms and be honest that the system is one of price regulation. We gain nothing by a verbal sleight of hand that turns losing your watch into a “choice” and the JCPA’s FOA into a “negotiation” between platforms and news.

In economics, we often ask about market failures. In this case, is there a sufficient market failure in the market for links to justify regulation? Is that failure resolved by this imposition?