This article is a part of the Antitrust's Uncertain Future: Competition in the New Regulatory Landscape symposium.

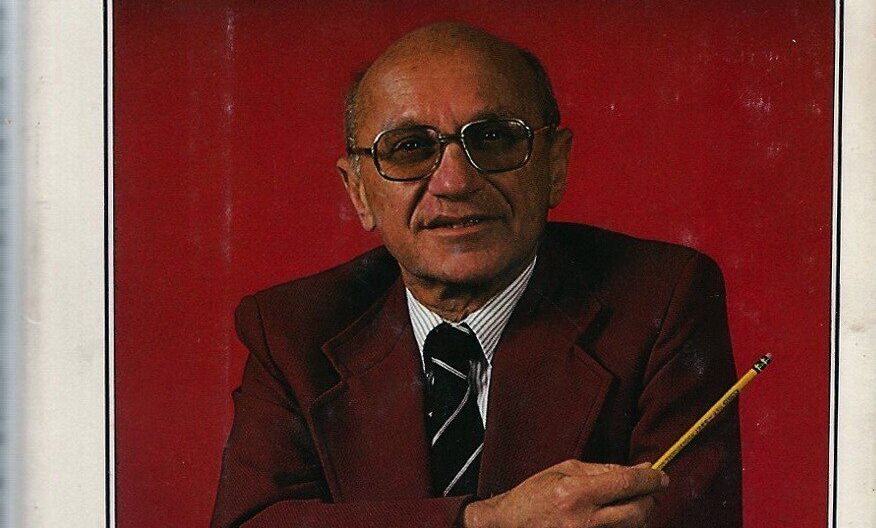

In Free to Choose, Milton Friedman famously noted that there are four ways to spend money[1]:

- Spending your own money on yourself. For example, buying groceries or lunch. There is a strong incentive to economize and to get full value.

- Spending your own money on someone else. For example, buying a gift for another. There is a strong incentive to economize, but perhaps less to achieve full value from the other person’s point of view. Altruism is admirable, but it differs from value maximization, since—strictly speaking—giving cash would maximize the other’s value. Perhaps the point of a gift is that it does not amount to cash and the maximization of the other person’s welfare from their point of view.

- Spending someone else’s money on yourself. For example, an expensed business lunch. “Pass me the filet mignon and Chateau Lafite! Do you have one of those menus without any prices?” There is a strong incentive to get maximum utility, but there is little incentive to economize.

- Spending someone else’s money on someone else. For example, applying the proceeds of taxes or donations. There may be an indirect desire to see utility, but incentives for quality and cost management are often diminished.

This framework can be criticized. Altruism has a role. Not all motives are selfish. There is an important role for action to help those less fortunate, which might mean, for instance, that a charity gains more utility from category (4) (assisting the needy) than from category (3) (the charity’s holiday party). It always depends on the facts and the context. However, there is certainly a grain of truth in the observation that charity begins at home and that, in the final analysis, people are best at managing their own affairs.

How would this insight apply to data interoperability? The difficult cases of assisting the needy do not arise here: there is no serious sense in which data interoperability does, or does not, result in destitution. Thus, Friedman’s observations seem to ring true: when spending data, those whose data it is seem most likely to maximize its value. This is especially so where collection of data responds to incentives—that is, the amount of data collected and processed responds to how much control over the data is possible.

The obvious exception to this would be a case of market power. If there is a monopoly with persistent barriers to entry, then the incentive may not be to maximize total utility, and therefore to limit data handling to the extent that a higher price can be charged for the lesser amount of data that does remain available. This has arguably been seen with some data-handling rules: the “Jedi Blue” agreement on advertising bidding, Apple’s Intelligent Tracking Prevention and App Tracking Transparency, and Google’s proposed Privacy Sandbox, all restrict the ability of others to handle data. Indeed, they may fail Friedman’s framework, since they amount to the platform deciding how to spend others’ data—in this case, by not allowing them to collect and process it at all.

It should be emphasized, though, that this is a special case. It depends on market power, and existing antitrust and competition laws speak to it. The courts will decide whether cases like Daily Mail v Google and Texas et al. v Google show illegal monopolization of data flows, so as to fall within this special case of market power. Outside the United States, cases like the U.K. Competition and Markets Authority’s Google Privacy Sandbox commitments and the European Union’s proposed commitments with Amazon seek to allow others to continue to handle their data and to prevent exclusivity from arising from platform dynamics, which could happen if a large platform prevents others from deciding how to account for data they are collecting. It will be recalled that even Robert Bork thought that there was risk of market power harms from the large Microsoft Windows platform a generation ago.[2] Where market power risks are proven, there is a strong case that data exclusivity raises concerns because of an artificial barrier to entry. It would only be if the benefits of centralized data control were to outweigh the deadweight loss from data restrictions that this would be untrue (though query how well the legal processes verify this).

Yet the latest proposals go well beyond this. A broad interoperability right amounts to “open season” for spending others’ data. This makes perfect sense in the European Union, where there is no large domestic technology platform, meaning that the data is essentially owned via foreign entities (mostly, the shareholders of successful U.S. and Chinese companies). It must be very tempting to run an industrial policy on the basis that “we’ll never be Google” and thus to embrace “sharing is caring” as to others’ data.

But this would transgress the warning from Friedman: would people optimize data collection if it is open to mandatory sharing even without proof of market power? It is deeply concerning that the EU’s DATA Act is accompanied by an infographic that suggests that coffee-machine data might be subject to mandatory sharing, to allow competition in services related to the data (e.g., sales of pods; spare-parts automation). There being no monopoly in coffee machines, this simply forces vertical disintegration of data collection and handling. Why put a data-collection system into a coffee maker at all, if it is to be a common resource? Friedman’s category (4) would apply: the data is taken and spent by another. There is no guarantee that there would be sensible decision making surrounding the resource.

It will be interesting to see how common-law jurisdictions approach this issue. At the risk of stating the obvious, the polity in continental Europe differs from that in the English-speaking democracies when it comes to whether the collective, or the individual, should be in the driving seat. A close read of the UK CMA’s Google commitments is interesting, in that paragraph 30 requires no self-preferencing in data collection and requires future data-handling systems to be designed with impacts on competition in mind. No doubt the CMA is seeking to prevent data-handling exclusivity on the basis that this prevents companies from using their data collection to compete. This is far from the EU DATA Act’s position in that it is certainly not a right to handle Google’s data: it is simply a right to continue to process one’s own data.

U.S. proposals are at an earlier stage. It would seem important, as a matter of principle, not to make arbitrary decisions about vertical integration in data systems, and to identify specific market-power concerns instead, in line with common-law approaches to antitrust.

It might be very attractive to the EU to spend others’ data on their behalf, but that does not make it right. Those working on the U.S. proposals would do well to ensure that there is a meaningful market-power gate to avoid unintended consequences.

Disclaimer: The author was engaged for expert advice relating to the UK CMA’s Privacy Sandbox case on behalf of the complainant Marketers for an Open Web.

[1] Milton Friedman, Free to Choose, 1980, pp.115-119

[2] Comments at the Yale Law School conference, Robert H. Bork’s influence on Antitrust Law, Sep. 27-28, 2013.