Last week the International Center for Law & Economics and I filed an amicus brief in the DC Circuit in support of en banc review of the court’s decision to uphold the FCC’s 2015 Open Internet Order.

In our previous amicus brief before the panel that initially reviewed the OIO, we argued, among other things, that

In order to justify its Order, the Commission makes questionable use of important facts. For instance, the Order’s ban on paid prioritization ignores and mischaracterizes relevant record evidence and relies on irrelevant evidence. The Order also omits any substantial consideration of costs. The apparent necessity of the Commission’s aggressive treatment of the Order’s factual basis demonstrates the lengths to which the Commission must go in its attempt to fit the Order within its statutory authority.

Our brief supporting en banc review builds on these points to argue that

By reflexively affording substantial deference to the FCC in affirming the Open Internet Order (“OIO”), the panel majority’s opinion is in tension with recent Supreme Court precedent….

The panel majority need not have, and arguably should not have, afforded the FCC the level of deference that it did. The Supreme Court’s decisions in State Farm, Fox, and Encino all require a more thorough vetting of the reasons underlying an agency change in policy than is otherwise required under the familiar Chevron framework. Similarly, Brown and Williamson, Utility Air Regulatory Group, and King all indicate circumstances in which an agency construction of an otherwise ambiguous statute is not due deference, including when the agency interpretation is a departure from longstanding agency understandings of a statute or when the agency is not acting in an expert capacity (e.g., its decision is based on changing policy preferences, not changing factual or technical considerations).

In effect, the panel majority based its decision whether to afford the FCC deference upon deference to the agency’s poorly supported assertions that it was due deference. We argue that this is wholly inappropriate in light of recent Supreme Court cases.

Moreover,

The panel majority failed to appreciate the importance of granting Chevron deference to the FCC. That importance is most clearly seen at an aggregate level. In a large-scale study of every Court of Appeals decision between 2003 and 2013, Professors Kent Barnett and Christopher Walker found that a court’s decision to defer to agency action is uniquely determinative in cases where, as here, an agency is changing established policy.

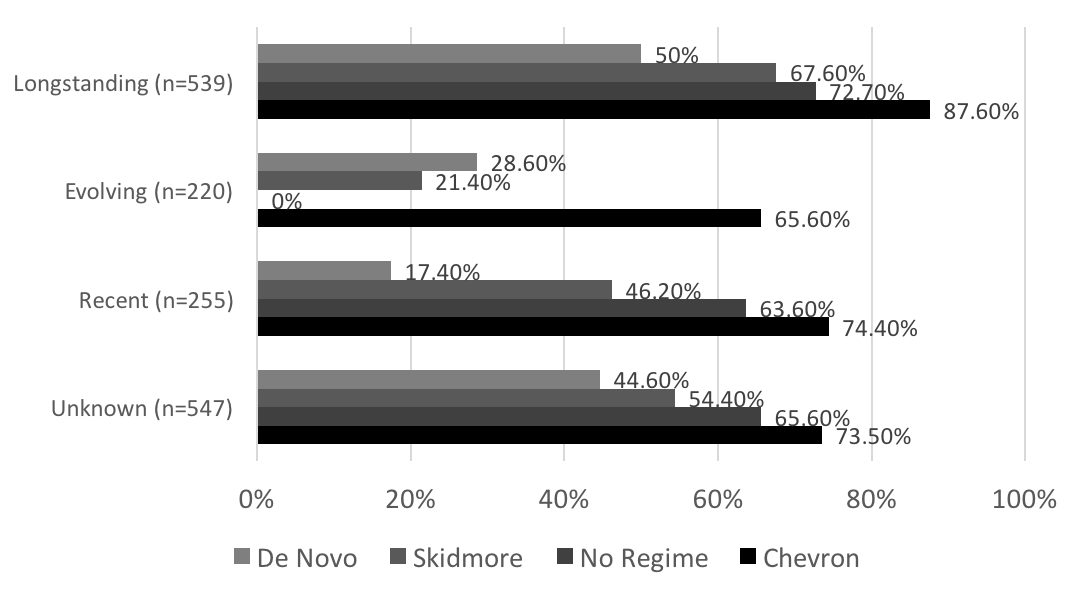

Figure 14 from Barnett & Walker, as reproduced in our brief.

As that study demonstrates,

agency decisions to change established policy tend to present serious, systematic defects — and [thus that] it is incumbent upon this court to review the panel majority’s decision to reflexively grant Chevron deference. Further, the data underscore the importance of the Supreme Court’s command in Fox and Encino that agencies show good reason for a change in policy; its recognition in Brown & Williamson and UARG that departures from existing policy may fall outside of the Chevron regime; and its command in King that policies not made by agencies acting in their capacity as technical experts may fall outside of the Chevron regime. In such cases, the Court essentially holds that reflexive application of Chevron deference may not be appropriate because these circumstances may tend toward agency action that is arbitrary, capricious, in excess of statutory authority, or otherwise not in accordance with law.

As we conclude:

The present case is a clear example where greater scrutiny of an agency’s decision-making process is both warranted and necessary. The panel majority all too readily afforded the FCC great deference, despite the clear and unaddressed evidence of serious flaws in the agency’s decision-making process. As we argued in our brief before the panel, and as Judge Williams recognized in his partial dissent, the OIO was based on factually inaccurate, contradicted, and irrelevant record evidence.

Read our full — and very short — amicus brief here.