Recently

Published

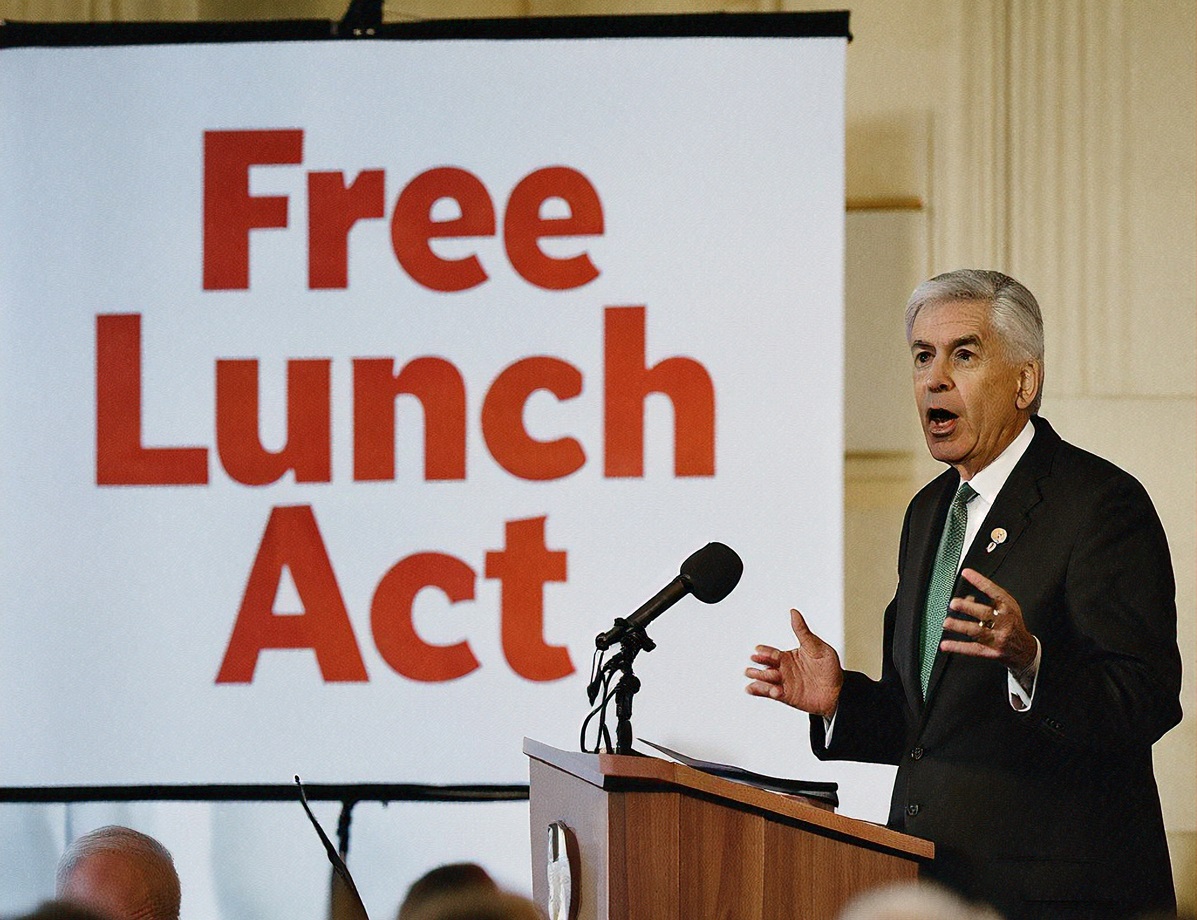

My high-school-aged son came home from school the day after Election Day in distress. His history teacher spent the entire class listing the Parade of Horribles in Project 2025 and its dire consequences for the United States. I asked my son, “Project 2025 is more than 900 pages. Do you think your teacher read it?” … What Project 2025 Can Tell Us About Brendan Carr’s FCC Priorities

More than a century ago, the U.S. Supreme Court held that the Sherman Act does not interfere with the “unquestioned right to stop dealing,” but the legacy of the Aspen Skiing is that terminating voluntary cooperation with a rival can give rise to liability. A case now on appeal could determine whether the “right to … Clarifying Antitrust Law by Straightening Teeth

In the aftermath of Hurricane Helene in September, SpaceX provided a masterclass in public relations by handing out thousands of Starlink satellite-broadband kits, waiving monthly fees, and enabling emergency alerts over cellular networks in affected areas. Not only did the effort generate significant goodwill for the company, but it also demonstrated that satellite technology can … FCC’s New Satellite Rules: Sharing Is Caring