The U.S. Justice Department (DOJ) and several states filed suit late last month against the property-management software firm RealPage Inc. for its “unlawful scheme to decrease competition among landlords in apartment pricing and to monopolize the market for commercial revenue management software that landlords use to price apartments.”

While this is not the first case to deal with so-called “algorithmic collusion,” it may nonetheless prove noteworthy to the extent that it signals a new approach that competition enforcers might take to such cases, and to anticompetitive agreements more generally.

Background of the Case

The complaint alleges that the three revenue-management systems RealPage offers to landlords—YieldStar, AI Revenue Management (AIRM), and Lease Rent Options (LRO)—serve to facilitate anticompetitive behavior by those landlords. These software systems, according to the RealPage website, help landlords to maintain “the most revenue-optimal position with precision pricing capabilities.”

There are, of course, perfectly legal ways for companies to maximize their income and profits. Some are even clearly pro-consumer, such as doing better marketing (more information for consumers), lowering costs, or improving the products on offer. There are other ways that are not so straightforwardly pro-consumer but not proscribed by antitrust law: it is legal, for instance, to gather information about competitors’ prices and even to match them.

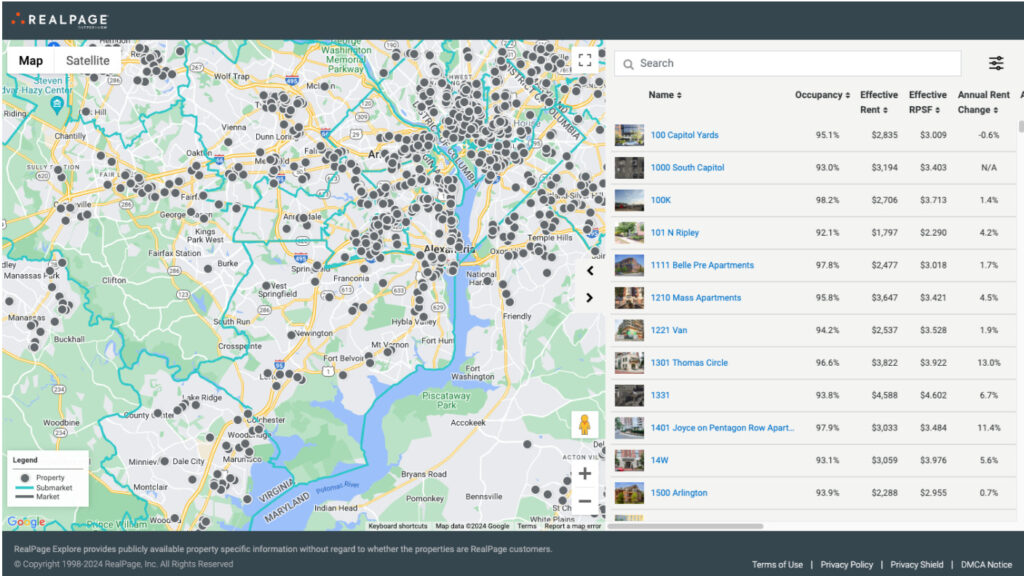

Landlords using RealPage in the DC/VA area. Available here.

What you cannot do is agree with your competitors—not in writing, not with a verbal “gentlemen’s agreement,” and not even inferred from other conduct or signals—to set a given price. That would amount to price collusion, also known as “the supreme evil of antitrust”. The DOJ complaint alleges that RealPage is facilitating precisely that among landlords, because their software isn’t just giving them public information, but also asks and provides nonpublic and highly sensitive information about rental prices and occupancy rates. Using that data, RealPage provides pricing recommendations (which have some “nudges”), suggesting that RealPage’s landlord users raise or lower rents based on the behavior of their competitors.

According to the complaint, these exchanges of information and recommendations have had the effect of increasing prices, or to “resist decreases in down markets as much as possible.” This is, assuming the facts alleged in the complaint are proven, a good example of a “hub & spoke” cartel, wherein competitors, rather than communicate directly with each other, coordinate their behavior through a third party that has a vertical relationship with each of them.

In line with these hypotheses, the complaint primarily relies on Section 1 of the Sherman Act, which prohibits “contracts, combinations, or conspiracies in restraint of trade.”

“Naked” agreements on price are those where the agreement is only about rising prices (or resist decreases) and does not have other aspects that may create efficiencies, such as sharing distribution costs or collaboration on research and development. Such agreements are analyzed under the per se rule, according to which there are no justifications for the conduct. A firm cannot argue as a defense, for example, that “the prices were too low,” that it is failing, or that there’s “too much competition.”

The DOJ also alleges that RealPage’s conduct violates Section 2 of the Sherman Act, which prohibits monopolization. They argue that RealPage’s “dominant position” in the market for commercial revenue-management software is maintained through anticompetitive practices, such as the use of competitively sensitive data and a “data scale advantage” as a barrier to entry.

Is It Relevant that Landlords Used Algorithms to Set Prices Above Competitive Level?

Not really, from a legal point of view, but it does make the DOJ’s case more credible. According to economic theory, cartels are “inherently unstable,” because their members have incentives to “cheat” on the agreement and make more money by selling at a cheaper price but in higher quantities. That’s why cartels need monitoring and sanction mechanisms. There must be a credible threat that, if one member of the cartel deviates from the agreement, the others can retaliate (lowering their prices even more and increasing production).

Algorithms could, however, make collusion easier to coordinate and sustain, especially in markets with a large number of firms (like the rental-housing market). Indeed, according to one OECD paper on algorithms and collusion:

As new automatic data collection processes become available, these technologies will likely be extended from electronic commerce to traditional markets (…). As a result, colluding companies will be able to increasingly monitor each other’s actions using sophisticated algorithms.

The data collected by automatic collection methods can then be monitored and combined with a pricing algorithm that automatically retaliates to deviations from an agreed price (…). Naturally, because algorithms are very fast at detecting and punishing deviations, firms do not have any incentive to actually deviate. Hence, unlike traditional cartels, it is very unlikely that price wars between algorithms will be actually observed, except if triggered by algorithmic errors.

This is precisely what the DOJ argues in this case. Collusion among landlords would generally be difficult (even in a small city or a ZIP code), because the number of existing or potential landlords makes it costly to reach an agreement. But RealPage software could, in theory, make it easier both to reach an agreement in the first place (collecting the information) and also to enforce it (through its “recommendations”).

Is ‘Algorithmic Pricing’ Always a Bad Thing?

No. Algorithms can also increase competition. According to that same OECD paper:

On the supply side, algorithms help increasing transparency, improving existing products or developing new ones. The OECD’s work on disruptive innovation has shown how market entry has been promoted by the ability of firms to develop new offerings based on algorithms (OECD, 2016e; OECD, 2016f and OECD, 2016g). This triggers a virtuous mechanism whereby companies are under constant pressure to innovate, thus promoting dynamic efficiencies (OECD, 2015a). The rise of algorithms on the supply side can also promotes static efficiencies by reducing the cost of production, improving quality and resource utilisation, as well as streamlining business processes.

On the demand side, algorithms may significantly affect the dynamics of the market by supporting consumer decisions: they better organise information so that it can be accessed more quickly and more effectively and they provide new information on dimensions of competition other than prices, such as quality and consumers’ preferences. Thus, algorithms have the potential to create positive effects on consumers and social welfare.

Dynamic pricing, as well, has served the purpose of improving market efficiency and benefiting consumers. Think of Uber, which has made it easier to get a cab on a busy night by increasing prices and thereby creating incentives for potential drivers to go out, rather than staying home.

Efficiencies are important here. Even if competitors agree on a price (Uber dictates the price for all drivers, which has the same effect), those wouldn’t be “naked” agreements. In addition to providing the positive incentives pointed above, ride-hailing apps reduce transaction costs and information asymmetries, and increase the opportunity to more efficiently deploy underutilized assets (See here).

Arguably, if a platform only makes a recommendation, the agreement is less likely to be anticompetitive because the competitors still determine their market conduct independently. Recommendations, of course, can be also pro-consumer, because—like Uber on a busy night—they can help the market to clear (e.g., Airbnb helping hosts to find a user, or users to find a place to stay) more quickly by recommending higher or lower prices.

What’s the Likely Outcome of the Case?

The case certainly does not look good for RealPage, as can be illustrated with just a couple of quotes from the opening of the complaint:

In its own words, RealPage “helps curb [landlords’] instincts to respond to down-market conditions by either dramatically lowering price or by holding price when they are losing velocity and/or occupancy… Our tool [] ensures that [landlords] are driving every possible opportunity to increase price even in the most downward trending or unexpected conditions”.

In fact, as RealPage’s Vice President of Revenue Management Advisory Services described, “there is greater good in everybody succeeding versus essentially trying to compete against one another in a way that actually keeps the entire industry down”. As he put it, if enough landlords used RealPage’s software, they would “likely move in unison versus against each other” (at 1, emphasis in the original).

We should, however, be cautious before predicting an outcome. RealPage argues that “it operates within legal bounds and does not harm competition.” The company claims that it “aggregates rental data from various sources rather than providing specific rates from competing properties, which he believes ensures the legality of their operations.”

I guess we will see. Similar complaints against RealPage (and landlords) filed by private plaintiffs are now in discovery.

It furthers complicates any prediction that the DOJ does not explicitly claim that RealPage facilitated a per se illegal price-fixing conspiracy (although the second claim for relief in the complaint certainly looks like a “hub & spoke” agreement). Instead, the complaint alleges only that the company distorted the competitive process by facilitating the exchange of nonpublic, competitively sensitive information about rents and building occupancy. Is the DOJ looking to expand the scope of Section 1 of the Sherman Act to include “the reduction of competitive uncertainty,” as competition law in the European Union would already proscribe?

The complications do not end there. As mentioned, the DOJ also claims that RealPage has “unlawfully monopolized the commercial revenue management market through unlawful exclusionary conduct. RealPage has amassed a massive reservoir of competitively sensitive data from competing landlords.” For this claim, the DOJ would need to define a relevant market and to prove that RealPage has monopoly power. It also must demonstrate the alleged conduct’s exclusionary effects, which is not an easy task. Can landlords not “multi-home” and use more than one software package? Can they not use other monitoring and pricing methods? Are competitors really excluded from the market because of RealPage practices?

In the meantime, I would suggest compliance-minded firms to be careful when implementing algorithmic pricing. As with any tool, it can be used for good, but some safeguards should be put in place in order to avoid the exchange of competitively sensitive information, and certainly any “recommendations” or agreements about future prices. Even a complicated lawsuit could be an unnecessary complication.