Following Monday’s announcement by the European Commission that it was handing down a €1.8 billion fine against Apple, Spotify—the Swedish music-streaming service that a decade ago lodged the initial private complaint that spawned the Commission’s investigation—published a short explainer on its website titled “Fast Five Facts: Facts that Show Apple Doesn’t Play Fair.” The gist of the company’s argument is that Apple engages in a series of unfair and anticompetitive practices. In this piece, we put some of these claims to the test.

Apple’s Allegedly Discriminatory 30% IAP ‘Tax’

Spotify’s first claim is that Apple imposes a “discriminatory” “tax” for use of its in-app purchase system. Right off the bat, this is deliberately misleading. Apple’s fee isn’t a “tax” any more than Spotify’s subscription fee is a “tax.” As pointed out in Lazar’s previous post, it’s relevant to go over how the App Store works.

Apple collects a fee to use its proprietary software and iOS (as well as to gain access to a customer base with which Apple has built considerable goodwill over the years) through a commission on its in-app purchasing system (IAP). Apple also charges a commission on paid apps. But most app downloads (86%) are free, in which cases Apple charges nothing. This arrangement can be sustained because Apple cross-subsidizes those free downloads by charging a commission on in-app purchases and paid downloads. This was acknowledged in the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals’ decision in Epic v. Apple.

In other words, Apple’s 30% “tax” (which, it should be noted, is the industry standard also charged by platforms like Microsoft, Google, and Sony) is, in fact, a fee for access to Apple’s proprietary software, platform, and user-base—all of which have taken Apple years of investment and goodwill to build. Even if Apple didn’t charge 30% through the IAP, it would still be entitled to collect a fee through some other means. With the current model, the cost of joining the App Store is lower, which particularly benefits small and non-game developers. Under a new model, free apps might have to shoulder some of that financial burden.

As for Apple’s fee being “discriminatory,” it is only “discriminatory” insofar as it is applied to paid apps and in-app purchases, but not to free apps. That is, by most accounts, a good thing, as it allows smaller apps (which are generally distributed free) to gain a foothold in the market.

This is not, however, what Spotify is claiming. Instead, Spotify claims that, e.g., Uber and Deliveroo do not pay the 30% fee simply because these services do not compete with Apple:

Does Apple Music pay it? No. Does Uber pay it? No. Deliveroo? No. Apple does not compete with Uber and Deliveroo. But in music streaming, Apple gives the advantage to their own services.

The suggestion is that Apple charges a fee to downstream competitors to give a leg up to its own services (in this case, presumably, Apple Music). But this is simply not true. Uber and Deliveroo’s exemption from the App Store fee is not due to the fact that they do not compete with Apple. Rather, Apple’s 30% fee only applies to digital goods and services (although not all digital goods and services; there are exceptions and counter-exceptions) that are subject to the App Store payment system.

Deliveroo and Uber, by contrast, both deliver physical goods and provide physical services and, thus, these companies utilize their own payment methods.

Preventing Spotify from Communicating with Users

Like most of Spotify’s claims, this one needs to be put into context. Spotify can share deals through any other means—just not through the app (and even this is only half true). For example, Apple’s anti-steering provisions don’t prevent it from advertising on billboards or buying TV spots (see here, here, and here). The company still has ample means to reach consumers.

The fact that Apple doesn’t allow Spotify to advertise on iOS in its preferred manner—i.e., directly and for free—doesn’t mean that Apple is a monopolist or that its conduct is anticompetitive. After all, Spotify also doesn’t allow businesses to advertise without paying a fee. Nor does it allow users to listen to music for free. That is because, like Apple, Spotify has costs that it has to cover, such as royalties, and investments it needs to recoup, such as app maintenance and quality-of-life improvements. It does this by charging users and advertisers a subscription.

Making It Difficult for Users to Upgrade Their Plans

What is “ease” in this context? What Spotify means by this is that Apple doesn’t provide the kind of ease that is most ideal for Spotify: a conspicuous one-click option to subscribe to Spotify Premium inside the app, without paying Apple a fee.

But “ease” doesn’t mean “easiest,” or “as easy as Spotify would like it to be.” In the context of an exploitative-abuse case like this one, the question should be if the process imposed for upgrading to premium truly downgrades the user experience to such an extent that it harms consumers.

Two concrete reasons suggest otherwise. First, the path to upgrading to Premium is not difficult unless one lowers the bar for the average Spotify user to new, unrealistic depths (on regulatory paternalism, see here). Second, despite Apple’s anti-steering provisions, Spotify can inform iOS users about the existence of premium plans inside the app—just not about pricing. It doesn’t take a genius to figure out that the next stop is an internet search.

Let’s start with the former. As Spotify, Netflix, and other app developers have found, the way around Apple’s IAP is no Sisyphean ordeal. Spotify doesn’t use Apple’s IAP, so it pays Apple nothing whenever a user subscribes to premium (in fact, Spotify doesn’t pay Apple anything ever). Payment happens entirely outside of the App Store. Users open a browser on their phone, tablet, or computer, sign up, and pay for the service. After that, they can access content via the app on their phone or tablet. This is a one-off process, except when subscribers seek to either upgrade or downgrade their plans—in which case, the process is to be repeated.

While this may require additional steps relative to making in-app purchases, it takes minimal effort even for a user with below-average internet-browsing skills, and adds a paltry 30 seconds to the registration/upgrade process (iOS even lets you sign up with facial ID and pay with Apple Pay on the website). Further, the marginal information cost goes from very low to zero after the user learns that payment needs to happen outside of the app, and does it for the first time. Or, put differently, once you know that you need to subscribe and upgrade from outside the app, you never have to relearn it again.

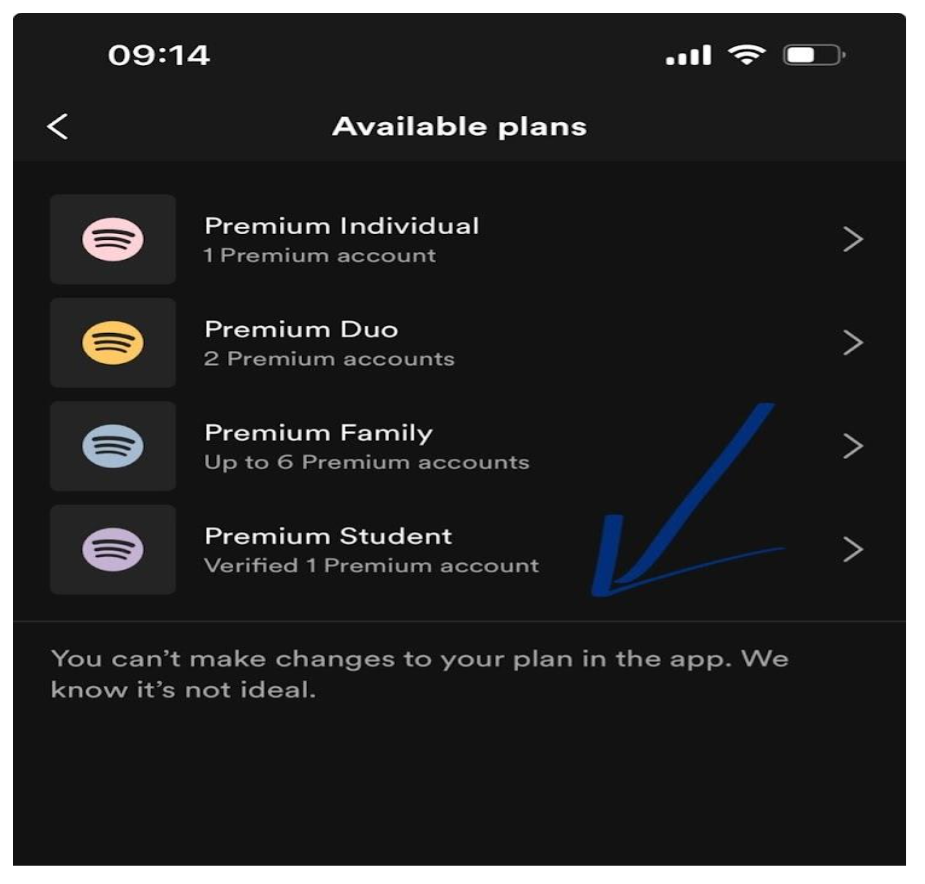

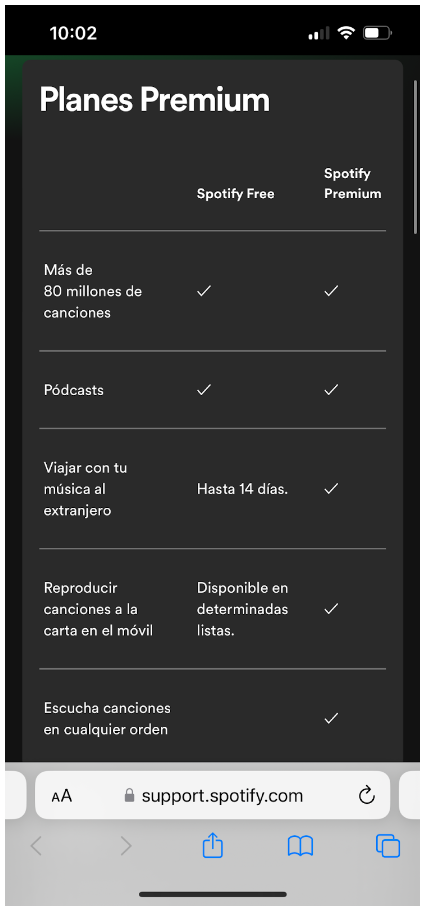

Next, Spotify claims that it can’t inform users that they have to use a browser to upgrade their plans or to point them in the right direction. But Spotify clearly informs users through the app that the app cannot be used to upgrade a subscription plan.

Spotify is also allowed to inform users about the existence of premium accounts and their advantages. When a user clicks on one of the above premium plans, he or she gets taken to the following website:

For free users, Spotify also schedules a vocal prompt to subscribe to premium after every two or three songs (“skip the ads, go Premium”). Once users learn that there is a premium version of the app (assuming they, in 2024, somehow didn’t know that when downloading the app), where else would they go?

It is clear that consumers are logically guided to the web by Spotify. If you can’t perform an act on an app version, the only logical inference is that it can be performed on the web version. This is especially obvious with a service where creating the account and paying for the recurring service took place through the web version.

Apple’s restrictions are in place to nudge distributors to use its IAP, which is how it recoups investments in its iOS and monetizes the App Store. As a result, a marginal group of consumers who would have otherwise subscribed to premium may keep using the free version—which, by the way, still gives Spotify significant advertising revenue. Of course, Spotify’s revenue would be higher still if everyone switched to premium, which appears to be the source of its gripe with Apple. But not actively helping Spotify to maximize its profits is not an antitrust offense, and nor should it be.

Even if one rejects the procompetitive justification for Apple’s anti-steering provision, as the Commission did in the decision it published Monday, it is questionable whether this constitutes consumer harm, and particularly whether it is the sort of harm that warrants antitrust intervention. Not everything that falls below the bar of Spotify’s ideal notion of “ease” harms consumers.

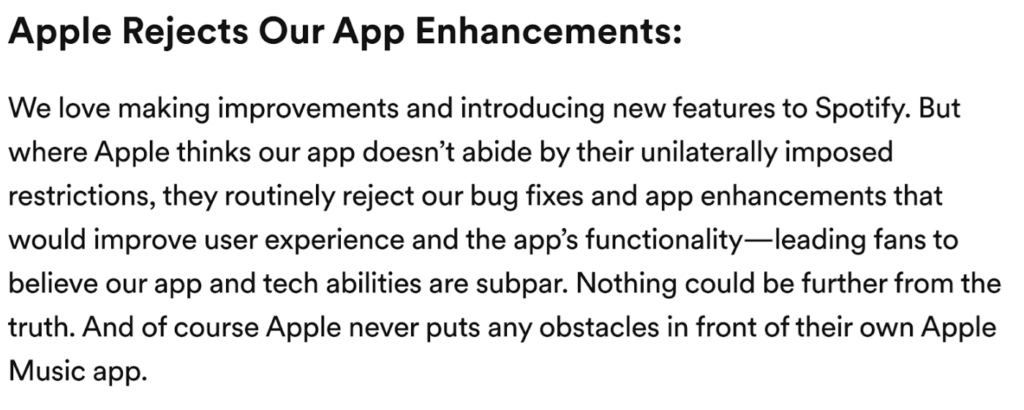

Rejecting Spotify’s App Enhancements

This is a strange claim, and one that we admit we are less competent to appraise without additional information. We do know, however, that Apple is notoriously cautious about the apps and updates it allows on the iOS. A single bad player or a single broken app can compromise the integrity of Apple’s hardware and the user experience that Apple strives to uphold across its products. This, in part, is why Apple has the safest operating system out there, especially compared to Android (see, for example, here).

Apple applies (or at least, used to apply, before the Digital Markets Act enters into force today) a two-tiered app-review process combining machine and human review to ensure that apps not only work properly and are scam and malware-free, but that they also do not include any objectionable content (such as pornography, social-engineering apps such as the “Blue Whale Challenge,” etc.). The alleged rejection of some of Spotify’s enhancements could be due to these safety or security concerns.

What would Apple stand to gain from undercutting Spotify, anyway? Is it that making Spotify worse would boost Apple Music, as the company seems to imply? Perhaps, but why compromise the quality of the iOS to monopolize relatively marginal adjacent market? Apple Music accounts for only about 6% of Apple’s total revenue, compared to 59% from the sale of phones and tablets. That would be like killing the goose that lays the golden eggs for one good meal (for a similar point in the Amazon/iRobot merger case, see here).

We are also skeptical about the suggestion that Spotify runs worse on iOS than elsewhere due to Apple blocking quality-of-life improvements. Anecdotal evidence suggests otherwise. According to one Reddit user, Spotify runs silky smooth on iOS compared to Android. One thread on Spotify’s official community forum is titled “Android app is horrible compared to iOS.” Are Spotify’s enhancements also being denied on all Android phones and tablets? That would be very unlikely (and I am not aware that Spotify has made such a claim).

Conversely, it seems that the Spotify/iOS combo has traditionally been the better deal because there were certain features available on iOS but not on Android, such as swiping left to put a song in the queue or right to add it to a playlist; visualizing a song’s remaining time; or the “equalizer” option. All of these features were pioneered on iOS before reaching Android. How could that be, if Apple is blocking Spotify’s enhancements?

Maybe the putative issues Spotify claims it faces on iPhones and iPads don’t actually have much to do with Apple maliciously denying the company the ability to improve its app. As Occam’s Razor posits, the simplest explanation is often the correct one. Maybe Spotify is simply using the momentum of the DMA and its 10-year-long campaign against Apple to blame the company for its developers’ own shortcomings, and to extract some rents in the process. To use a term popular in European regulatory circles and the DMA’s lexicon, that seems unfair.

Conclusion

According to Spotify, Apple’s rules exist for one reason only:

to give Apple an unfair advantage over the many other services that are working hard to compete for fans. For competition to work and innovation to thrive, Apple needs to play fair.

While Spotify may perceive certain aspects of Apple’s policies to be restrictive or unfair, it is essential to evaluate these claims critically and consider the broader context. Doing that, we see that some of these claims are overblown, taken out of context and, indeed, unfair in their own right. Ultimately, not everything that falls short of Spotify’s ideal version of its relationship with Apple is anticompetitive, unfair, exploitative, or a herald of monopolization.