This article is a part of the The FTC's New Normal symposium.

Before becoming chair of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), Lina Khan advocated the use of rulemakings to implement the prohibition on unfair methods of competition (UMC) in Section 5 of the FTC Act. As chair, she proposed a rule, which likely will be finalized in the spring, to ban noncompete clauses in employment contracts. But I expect a court to quash this bold assertion of quasi-legislative power.

The FTC exercised power over a single industry in the 1970s, when it required gas stations to post octane ratings for the gas they sold. In promulgating that rule, the FTC cited both Section 5 powers—the competition-protection power to proscribe unfair methods of competition, and the consumer-protection power added in 1938 to proscribe unfair or deceptive acts or practices (UDAP).

In the wake of the octane-posting rule, Congress passed the Magnuson-Moss Act, which established procedures for future consumer-protection rules. Congress did not address rules to implement the prohibition on unfair methods of competition, but it is implausible that Congress intended to allow the FTC to promulgate such rules without similar procedures.

In the rush to pass a bill before the end-of-year recess, a single speech was permitted before the final vote in the House. Among the points Rep. Jim Broyhill (R-N.C.) felt compelled to make was that the FTC had no authority to promulgate a competition rule.

In the years since the Magnuson-Moss Act became law in 1975, the FTC did not assert the power to promulgate a competition rule, until the noncompete ban. The FTC relies on Section 6(g) of the FTC Act. Section 6 grants the FTC various powers, and (g) provides: “From time to time to classify corporations and to make rules and regulations for the purpose of carrying out the provisions of this Act.”

Within this awkward passage, ambiguity lurks in the word “and.” Consider a licensing fee for “black and white cats.” If “and” joins “black” with “white,” only tuxedo cats are taxed, but if “and” distributes “cats” over “black” and “white,” tuxedo cats go scot-free. The meaning of an ambiguous “and” is the issue in a case set for U.S. Supreme Court argument on the first Monday in October.

Even if “classify corporations” is a distinct power from “make rules and regulations,” the juxtaposition of the two implies a connection. “It is a fundamental canon of statutory construction that the words of a statute must be read in their context and with a view to their place in the overall statutory scheme.”

To “classify corporations” is an obscure concept now, but it was not when the FTC Act was written. It meant to treat different corporations differently for specified purposes. Reporting and disclosure were the purposes Congress had in mind with the FTC Act, and Section 6(g) empowered the FTC to promulgate rules and regulations to achieve those purposes.

The language that ended up in Section 6(g) started out as part of the original House bill to create the FTC. But that bill did not contain a prohibition on unfair methods of competition or grant any enforcement powers. In “carrying out the provisions of this Act,” the FTC would have acted merely as a clearinghouse for information.

In upholding the octane-posting rule, the D.C. Circuit construed Section 6(g) as a grant of power to promulgate rules enforcing Section 5. But the court made a fatal error by relying on words not in the statue. The court relied on Section 6(g) as codified, and yet it was well-established that the codification of a statute “cannot prevail over the Statutes at Large when the two are inconsistent.”

In the U.S. Codes of 1940 to 1970, the phrase “provisions of this Act” was codified as “provisions of sections 41 to 46 and 47 to 58 of this title,” i.e., 15 U.S.C. §§ 41–46, 47–58 (skipping § 46a). Because Section 5 was codified as 15 U.S.C. § 45, the D.C. Circuit held that Section 6(g) specifically referred to Section 5. But it did not. And the U.S. Code from 1976 to the present has codified the phrase as “provisions of this subchapter,” just as in the original 1926 U.S. Code.

When the D.C. Circuit’s erroneous interpretation of section 6(g) is set aside, as it must be, we are left with a statutory text that does not unambiguously grant broad rulemaking powers. And the drafting history of the FTC Act indicates Section 6(g) could not have granted broad rulemaking powers.

After the House passed a bill to create the FTC, the Senate took up and passed a substitute for the House bill. The bill passed by the House prohibited nothing and granted no enforcement powers over marketplace conduct. The bill passed by the Senate prohibited unfair methods of competition and gave the FTC concomitant enforcement powers, but it conferred no powers “to make rules and regulations.”

The reconciliation of the bills was governed by the “Manual of the Law and Practice in Regard to Conferences and Conference Reports,” which barred inclusion of anything in a conference report that had not been passed by either house. Because neither house had granted rulemaking powers, the compromise worked out in conference could not grant such powers.

Nor can any hint of broad rulemaking power be found in the conferees’ comments when they presented the compromise bill. In contrast, the legislative history provides numerous statements that the prohibition on unfair methods of competition was to be enforced through case-by-case adjudication. Section 6(g) merely authorized rules and regulations for the forgotten task of classifying corporations.

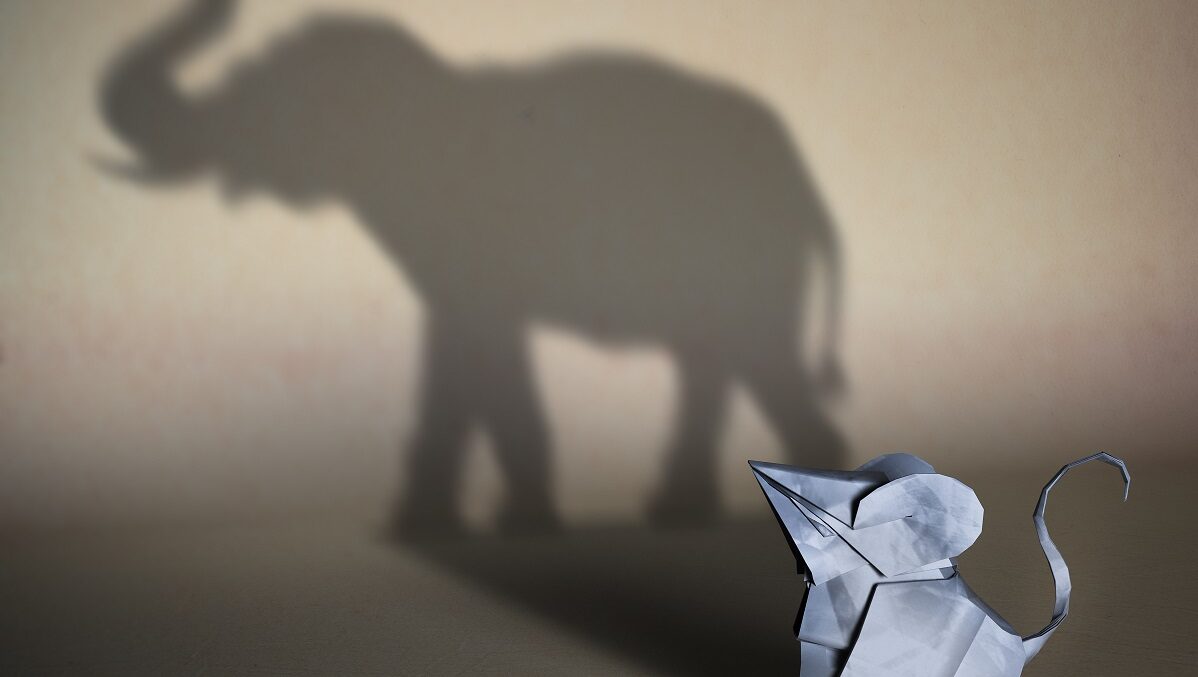

A court interpreting Section 6(g) should apply the modern legal maxim that Congress does not “hide elephants in mouseholes.” To be sure, Section 6(g) was a mousehole; it accounted for less than 5% of the words in Section 6. Section 6(g) was large enough for the mouse of classifying corporations, but not for the elephant of making rules binding on every economic actor in the economy.