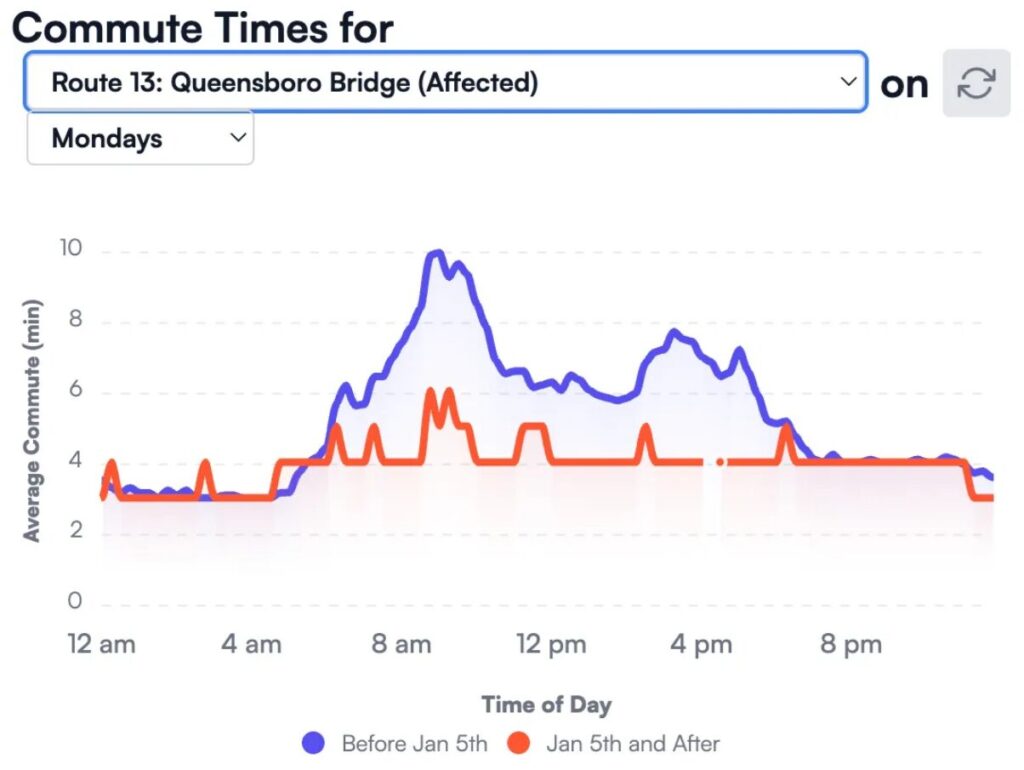

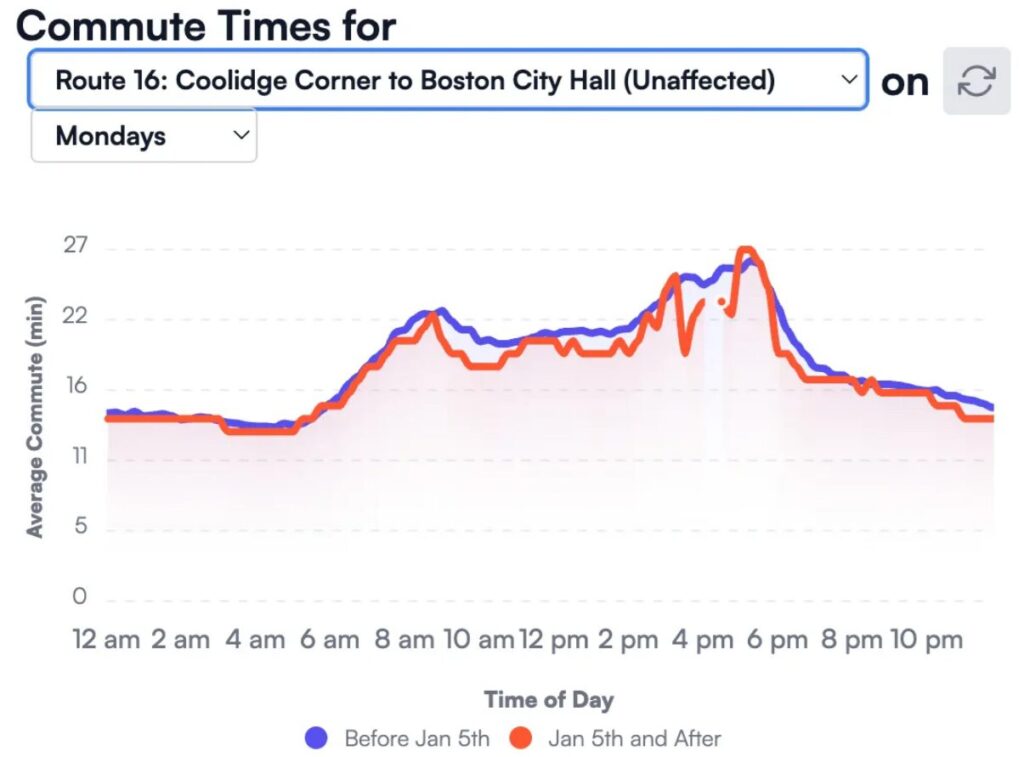

The early data from New York City’s congestion-pricing experiment is rolling in. If you look at affected routes, you see a clear drop when the fee kicks in.

For routes that are unaffected, we saw no change.

So far, it seems the basic prediction from supply and demand holds true. When the price of driving into Manhattan is raised, fewer people drive into Manhattan. I’m as surprised as you are.

But economic theory tells us more than just “demand slopes down.” It helps predict who responds most to price changes through demand elasticity. Consider some examples:

Jack commutes daily from Brooklyn, but has a subway line two blocks from his apartment. The $9 charge makes him rethink his driving habit—he can easily switch to transit and save the fee with only a slight increase in commute time. That flexibility means his demand will be highly elastic.

At the other end of the spectrum is Sarah, a high-powered attorney billing $800 per hour. The time saved driving versus transit is worth far more than the congestion charge—her demand is highly inelastic. Similarly for Jane’s delivery service, which generates $500+ in revenue per-vehicle per-day in Manhattan. The fee is a minor cost of doing business.

In between, there’s Bob, who is visiting from Ohio for a weekend Broadway show. He may use Uber or Lyft to get around Manhattan, just as he was used to before the charge. His demand is relatively inelastic, since he wants door-to-door service in an unfamiliar city. From the driver’s perspective, since the fee gets spread across many passenger trips, ride-share services keep operating as before and simply pass through small fare increases for each ride.

In practice, we don’t have this individual-level data. So, how would these insights show up in the data we do have?

We can look at different types of vehicles. Personal vehicles entering Manhattan typically make just two trips—in and out. If the price of those trips rises too high relative to alternatives (public transit, carpooling, or just not making the trip), these drivers will change their behavior. Their demand is relatively elastic.

In contrast, taxis and Ubers operate very differently. They make multiple trips within the zone, serving passengers who have already demonstrated they’re willing to pay a premium for door-to-door service. The congestion charge gets spread across multiple revenue-generating rides. Plus, these drivers’ entire business model depends on being in Manhattan—they can’t simply choose not to enter. Their demand is much more inelastic.

Michael Ostrovsky hired research assistants to look at traffic patterns at different locations. At the Holland Tunnel and other entry points—where personal vehicles dominate—congestion dropped significantly after pricing was implemented. In contrast, within the congestion zone itself—where taxis/Uber make up a much larger share of traffic—congestion remained largely unchanged.

This variation in elasticity shapes the distributional impact. Those with inelastic demand keep driving, but pay more into the coffer. Those with elastic demand change behavior to avoid the charge. The people who stop driving are those who value entrance near the charge amount.

Importantly, this sorting effect is a feature, not a bug. The goal is to reduce congestion by discouraging marginal trips while allowing high-value uses to continue with less traffic. Economic theory predicts the charge will push out lower-value trips first, improving efficiency.

My initial reaction is, of course, pure joy. Another W for supply and demand.

Is Congestion Pricing a Good Policy?

Economists seem to love congestion pricing as a policy, not just a validation of our theory. Why? The standard theory suggests that roads are a common resource that individual drivers overuse because they don’t account for how their driving affects others. When I decide to drive into Manhattan, I consider my own time costs from traffic, but not how I slow down everyone else. My driving creates an externality on other drivers.

The solution? A Pigouvian tax. Make drivers face a price that reflects the full social cost of their trip, including the congestion they create for others (and all other externalities as well—say, on walkers).

In theory, that’s what congestion pricing tries to do. By charging drivers to enter Manhattan during peak hours, it forces them to account for their impact on traffic. Those who really need or value driving will pay the fee and continue, while others will shift to public transit, alternative routes, or different times. The reduced traffic means faster trips for those who do drive. Basic supply and demand predicts all of this.

But here’s where I think people are getting ahead of the argument: just because congestion pricing reduces traffic doesn’t automatically make it welfare-improving.

To understand why we need to think carefully about the level of the congestion price, consider an extreme example. If New York City set the congestion charge at $1,000, what would happen? Only emergency vehicles and extremely high-value business trips would probably continue. A hedge fund manager rushing to close a $1 billion deal might gladly pay. But this is clearly excessive—it would eliminate many socially valuable trips where the benefits exceed the congestion costs. So, it’s not enough to say decreasing demand is a good thing.

Most economists seem to be coming from the other extreme. Assume away absent transaction costs of implementing the policy—which, to be clear, do matter, but go with me for a second—and assume the additional tax revenue isn’t actively harmful. In that case, you’d see an unambiguous improvement in welfare from a small tax. A tax of $0.01 better aligns private costs with social costs, assuming driving creates a negative externality.

So where is the actual $9 fee along this spectrum? I don’t know.

But we need to think seriously about costs and benefits to assess whether this policy actually improves society. First, what exactly are we comparing to what? The welfare analysis has to specify the counterfactual—what would have happened without the policy? Are we comparing to a world with completely unpriced roads? Or to the previous system of bridge tolls that already incorporated some congestion pricing? What if parking is being priced? The welfare implications differ depending on our baseline.

Second, we need to account for all the changes in behavior, not just reduced Manhattan traffic. If drivers reroute to avoid the charges, they may create new congestion problems elsewhere. Early data shows increased traffic on some alternate routes, although not a ton. These displacement effects create new costs that offset some of the benefits of reduced Manhattan congestion. It likely doesn’t change whether the policy is clearly welfare-enhancing, but could on the margin, if it was borderline without considering this effect.

Third, congestion pricing doesn’t just change who drives; it also shifts economic rents in related markets—particularly parking. In Manhattan, where parking supply is highly inelastic, the fees may simply transfer rents from parking-lot owners to the government, without significantly reducing traffic in the short term. That doesn’t seem to be the case so far, since traffic is down, but it’s possible. Parking-lot owners, who previously captured high profits from a captive driving market, now face reduced demand, as fewer cars enter the city. These lost quasi-rents are effectively redirected to the government through congestion fees. Over the longer term, however, this shift could spur a reallocation of land use—parking lots might convert to higher-value uses like housing or commercial developments, amplifying the efficiency gains of the policy. But in the near term, it’s worth considering whether these transfers are just reshuffling value, rather than creating new welfare gains.

Finally—and most importantly, in my eyes—what happens to the revenue matters enormously for welfare analysis. If the funds are used to improve infrastructure or reduce other distortionary taxes, that amplifies the welfare gains. If, however, the money is captured by special interests or spent inefficiently, the net benefits are reduced. Unlike a standard explanation of Pigouvian tax—where we often ignore what happens to the revenue and just assume that a tax of $1 generates $1 of social benefit—here, how the money gets spent is central to the welfare calculation.

Consider two extremes: In one case, the revenue funds perfectly targeted infrastructure improvements that benefit the exact people paying the charges. That’s basically a user fee—drivers pay for better roads, which they value. The policy has found a way to completely internalize that program to drivers.

On the other hand, money completely disappears into wasteful spending. Now, it’s just a pure tax on driving with associated deadweight loss. Yes, driving generates an externality, but a wasteful tax also has an externality.

The reality lies somewhere in between, but where exactly it lies shapes the welfare impact. Here, I think we need to take New York City’s track record seriously when thinking of congestion pricing as a benevolent Pigouvian tax versus simply lighting dollars on fire.

To be clear, none of this negates the basic economic logic of congestion pricing. The empirical evidence from New York and other cities suggests it can significantly reduce traffic. And there’s a strong theoretical case that some form of road pricing is improvement over completely unpriced access.

Any careful welfare analysis, however, would require wrestling with questions about revenue usage, displacement effects, and distributional impacts. The simple story of “make drivers pay for congestion externalities” captures an important truth, but misses crucial complexities.

My tentative view? New York City’s policy will likely generate net benefits despite implementation flaws. The congestion costs in Manhattan are so large that even an imperfect pricing scheme probably improves welfare. Some usage fee is good, but reasonable people can disagree based on how they weigh different factors, especially how much money will be spent in New York.

The broader lesson is that, while supply and demand give us powerful tools for predicting behavior, moving from positive predictions to welfare conclusions requires careful analysis of costs and benefits.

The Power of Simple Economic Truths

As economists, we sometimes get caught up in complex models and sophisticated empirical methods. But New York’s congestion-pricing experience reminds us of a simple truth: prices matter. When something becomes more expensive, people do less of it. Moreover, those with good alternatives or who value it less cut back first.

Every day, supply and demand racks up the wins over other theories. This pattern appears across markets. Consider a forthcoming paper from Andrea Mense in the Journal of Political Economy: Macroeconomics. The paper shows that increasing the housing supply reduces rents. Again, not exactly shocking to anyone who thinks about supply and demand. Yet, many people actively dispute the idea that increasing supply decreases demand for housing. See this post where I explain how even Scott Alexander slips up on these issues.

It sounds almost embarrassingly basic. That’s probably why most economists don’t spend much time on it. In policy debates, however, this simple logic often gets lost. People focus on… I don’t know… other things? Fairness? Rights? I can’t quite make sense of it.

Yes, there are always complications and nuances beyond supply and demand. Yes, other considerations like equity matter enormously for policy design. But we can’t wish away the fundamental relationship between prices and behavior. No amount of moral reasoning changes the fact that higher prices reduce the quantity demanded.

That’s why, even if it feels unsophisticated to keep hammering these basic points, we must continue to do so. When public discourse routinely ignores or denies simple economic relationships, restating them becomes vital—not because they’re the only thing that matters, but because they’re the foundation upon which everything else builds. That’s why we’re here, hammering the basics.