The 2024 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences (or simply THE Nobel Prize, as I call it) was awarded this morning to Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James Robinson “for studies of how institutions are formed and affect prosperity.” I called last year’s prize to Claudia Goldin “a surprise to no one.” This year’s prize is even less of a surprise. Acemoglu is the second-most-cited living economist.

At the heart of Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson’s (AJR) work is a simple question: How do political institutions fundamentally shape the wealth of nations? This immediately raises a crucial follow-up question—what shapes these institutions? AJR won the prize for the back-and-forth between those questions. Really, not for the questions asked or for the answers given, but for the empirical and theoretical tools used to answer those questions.

The Colonial ‘Natural Experiment’

AJR’s most famous and influential papers (known simply as AJR 2001 and 2002) used the colonial experience as a natural experiment to study how institutions affect long-term prosperity. Their key argument was that colonial strategies had lasting impacts on institutional quality, which drove economic outcomes. So they try to establish a causal arrow from institutions to economic outcomes.

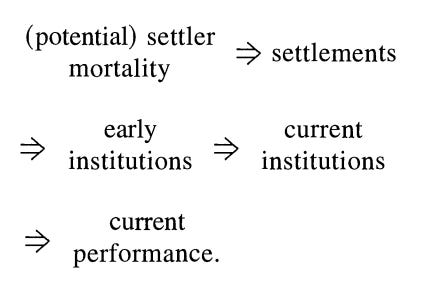

For example, their famous “settler mortality” paper (AJR 2001), proposed the following mechanism:

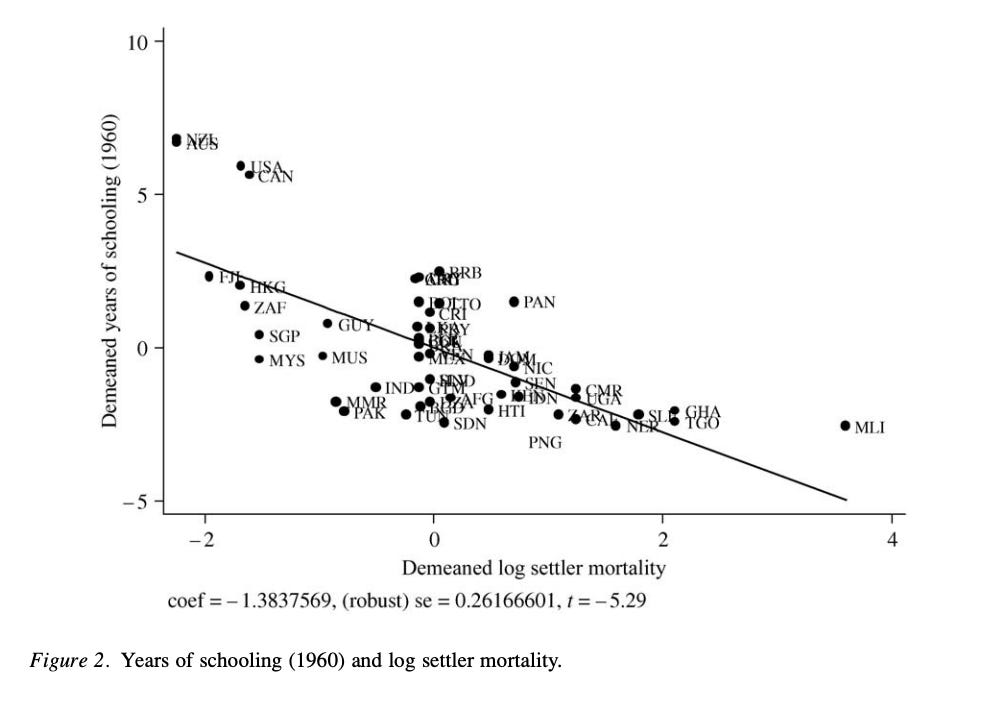

Empirically, they found that, in places where European settlers faced high mortality rates, they set up extractive institutions designed to transfer resources back to Europe. In contrast, where mortality was low, settlers established inclusive institutions that replicated European ones, with more substantial property rights and checks on government power. Crucially, they argued that these initial institutional choices persisted long after independence.

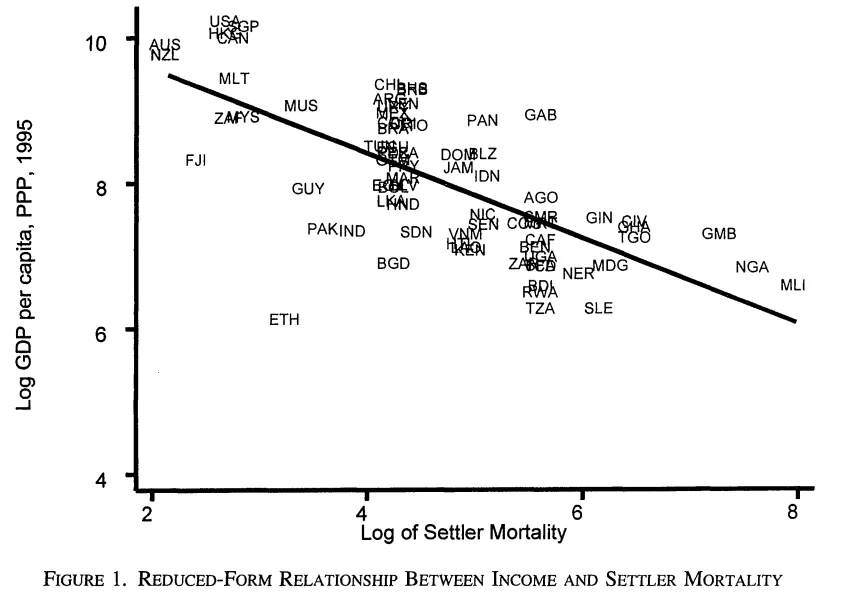

They see this in the simple reduced-form data. As it turns out, this data isn’t so simple. More on that later.

AJR’s work was at the junction between old-school cross-country growth regressions and modern economic history. The critical difference was finding plausible(?) instrumental variables to move beyond ordinary least squares (OLS) and claim some sort of causality.

To establish causality, they used early European settler-mortality rates as an instrument for institutional quality. In places where Europeans faced high mortality (like tropical areas with malaria), they set up extractive institutions designed to transfer resources back to Europe. Grab and get out. But in places like Canada and the United States? Different story. The weather was nicer, fewer deadly bugs, and, suddenly, colonizers could think long term and that carried through to today. There are lots of chains in that argument, but it is the basic idea.

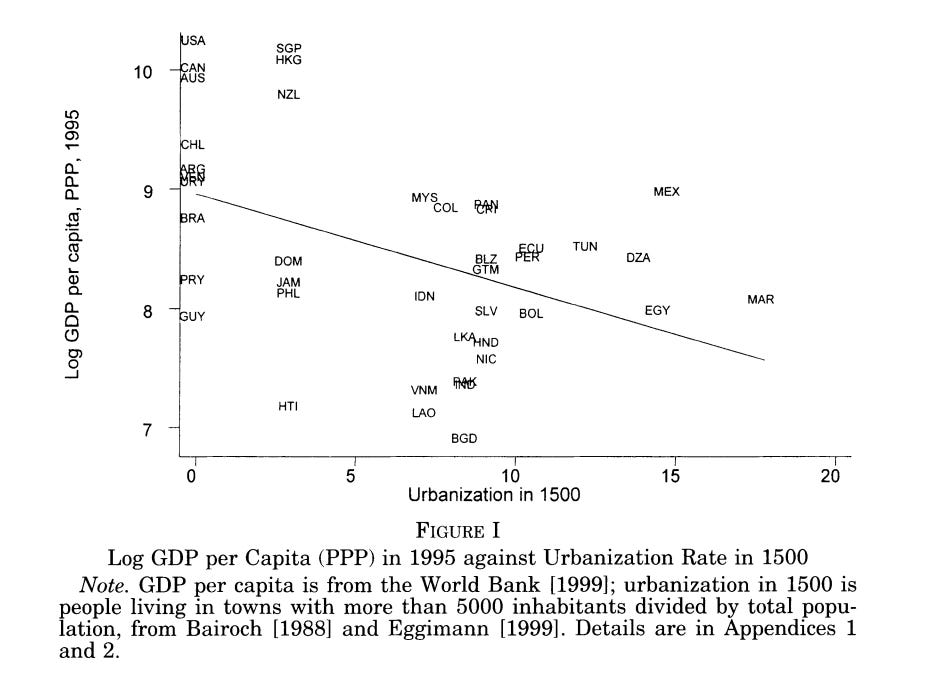

Similarly, their “reversal of fortune” paper (AJR 2002) documented a striking pattern—among former colonies, places that were relatively rich in 1500 are now relatively poor, and vice versa. Since things like geography haven’t changed, this posed a challenge for purely geographic explanations of development.

AJR argued this reversal reflects the institutional consequences of colonization. Europeans were more likely to establish extractive institutions in initially prosperous, densely populated areas. This led to a reversal in relative incomes over time, as inclusive institutions fostered growth in initially poorer settler colonies.

‘Early’ Political Economy Models

Just as AJR were, early on, applying modern empirical tools of causal inference to political economy and development, they were relatively early on the theory side, too. It’s weird to say they are early on any of this stuff, since Doug North won a Nobel in 1993 for many of these same topics. But they really brought the tools of game theory, which took off in the 1980s and 1990s.

AJR (especially Acemoglu and Robinson) developed models to explain why growth-promoting institutions are (or aren’t) adopted and why inefficient institutions can persist.

For example, take Acemoglu & Robinson (2000). A key mechanism in their models is the commitment problem between elites and citizens. Even when more inclusive institutions would increase overall prosperity, elites may block reforms because they can’t credibly commit to compensating themselves once they give up power. These models help explain the persistence of extractive institutions, even when they reduce overall economic performance. They also shed light on the conditions under which democratic reforms occur.

To sum up, AJR won the prize for:

- Using historical natural experiments to study big macro questions;

- Highlighting the central role of institutions in economic development; and

- Formal modeling of institutional change and persistence.

These contributions have shaped how economists think about long-run prosperity, regardless of debates over specific empirical results. Beyond any individual finding, AJR’s work represents a broader economic shift toward studying the deep historical roots of contemporary outcomes. They helped bring political economy and economic history into the mainstream of economics.

Lots of Debate

Of course, no research agenda at this scale is without critics. But I think there is something unique in this case that deserves mention. I’ll mention two papers to give a flavor of the debate: Edward L. Glaeser, Rafael La Porta, Florencio López de Silanes, & Andrei Shleifer (2004) and David Y. Albouy (2012).

Glaeser et al. focus first on the measurement of institutions. They argue that AJR’s measures, such as constraints on the executive, reflect outcomes rather than durable constraints. This is always the debate here. Everything is determined together in equilibrium.

They argue that the high volatility and mean reversion of these measures, compared to more stable variables like education levels, undermines AJR’s claim to be capturing deep institutional differences. This casts doubt on whether AJR are truly measuring what they claim to be measuring.

Glaeser et al. argue that AJR’s proposed instruments—settler mortality and indigenous population density—are even more strongly correlated with things like human capital than with institutions.

This opens up the possibility that European settlers brought human capital rather than just institutions, providing an alternative explanation for the relationship between settlement patterns and development.

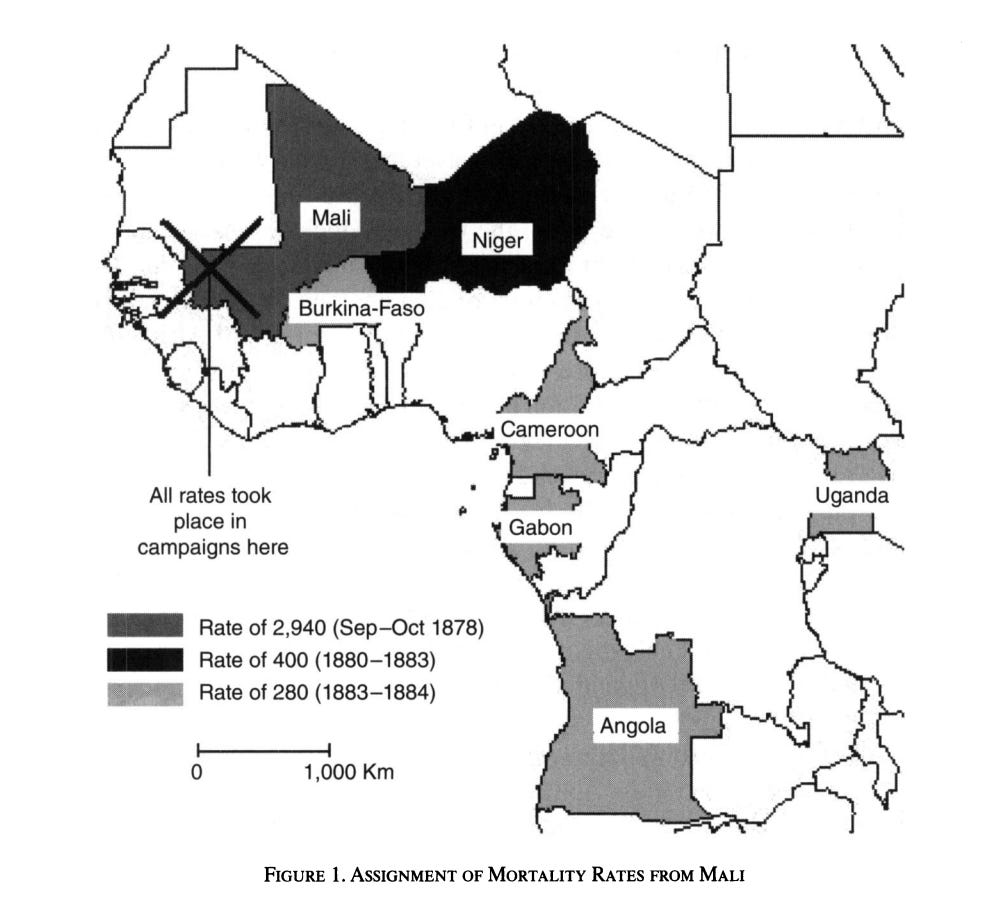

The most direct issues surround the data and empirical strategy. Albouy’s critique of AJR’s data is particularly important to understand. He identifies several problems with the construction and interpretation of the settler-mortality data.

Albouy’s Figure 1 casts doubt on their strategy. AJR assign Mali itself an extreme rate of 2,940 per 1,000, based on a brief yellow fever outbreak, while neighboring Niger receives a rate of 400 from a different time period. Even more perplexingly, countries as distant and diverse as Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Gabon, Angola, and Uganda are all assigned an identical rate of 280, derived from yet another time span in Mali. The wild swings in assigned mortality—from 280 to 2,940 among neighboring states—suggests the results may not be completely robust to different data classifications. Maybe the results reflect empirical choices and fleeting events rather than persistent institutional or environmental factors.

Again, this Nobel is about something other than whether AJR got all the answers right. No one would say the answer is 100% yes. It’s about the questions they asked and the tools they developed to answer them. That may seem weird to outsiders but that’s fairly normal in economics. For example, the prize to Douglas W. Diamond and Philip H. Dybvig was like this. They provided a tool to think about bank runs, not that they gave the best explanation of bank runs.

As Alex Tabarrok pointed out, one thing that makes AJR unique within economics is that much of their work is later summarized in books: “The Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy,” “Why Nations Fail,” and “The Narrow Corridor“—all by Acemoglu and Robinson—and “Power and Progress” by Acemoglu and Johnson.

While “Why Nations Fail” is worth reading as a summary of the AJR project, I’d suggest “How the World Became Rich” from Mark Koyama and Jared Rubin for an overview of this field of economic history, development, and growth.

Despite the debates and critiques surrounding AJR’s work, their contributions to the field of economics are undeniably significant. They pioneered new approaches to studying the long-term impacts of institutions on economic development, bringing sophisticated empirical methods and game-theoretic models to bear on fundamental questions of political economy. The Koyama and Rubin book wouldn’t be possible without the field AJR ignited. They sparked a renewed interest in the historical roots of contemporary economic outcomes and helped bring political economy and economic history into the mainstream of economics.

As with many Nobel-worthy research agendas, AJR’s work has opened up new avenues of inquiry and debate that will likely occupy economists for years to come. Their Nobel Prize recognizes not just their specific findings, but their role in reshaping how we think about and study the deep determinants of economic prosperity.