The U.S. Supreme Court’s recent decision in Loper Bright v. Raimondo may have added a new wrinkle to the decades-long fight over whether broadband internet-access services should be classified as “telecommunications services” under Title II of the Communications Act.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has flip-flopped multiple times over the years on this hotly debated classification, popularly known as “net neutrality.” Now, broadband providers are challenging the most recent reclassification, from earlier this year, in the 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

The case hinges on whether broadband internet is an “information service,” subject to relatively light-touch regulation under Title I, or a “telecommunications service,” subject to utility-style common-carrier regulation under Title II. The key legal dispute is whether the FCC is authorized to yet again reclassify broadband access as a Title II service.

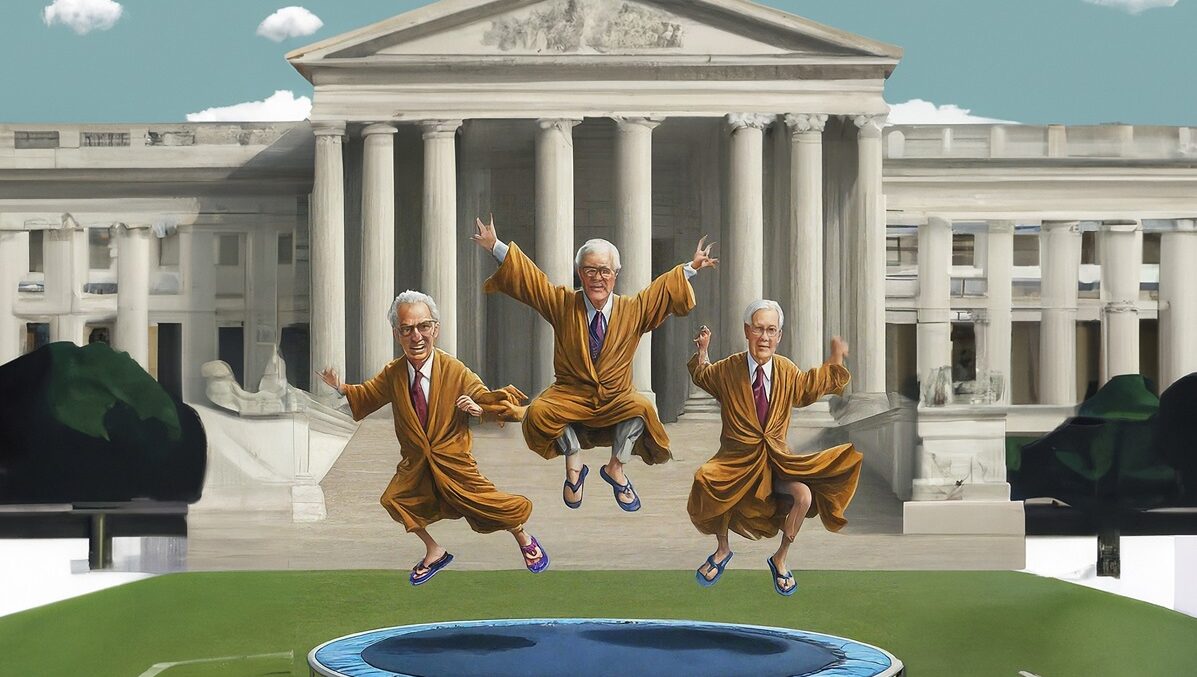

But the recent Loper Bright decision overturned the Supreme Court’s longstanding principle of granting “Chevron deference” to agency interpretations of ambiguous statutes. In its opinion, the Court noted that such deference often results in substantial flip-flops in regulatory regimes from one administration to the next, even as there has been no change in the statutes governing those regulations. In his concurrence, Justice Neil Gorsuch explicitly identified the FCC’s repeated broadband-reclassification U-turns as among the most striking examples of this phenomenon:

How bad is the problem? Take just one example. Brand X concerned a law regulating broadband internet services. There, the Court upheld an agency rule adopted by the administration of President George W. Bush because it was premised on a “reasonable” interpretation of the statute. Later, President Barack Obama’s administration rescinded the rule and replaced it with another. Later still, during President Donald J. Trump’s administration, officials replaced that rule with a different one, all before President Joseph R. Biden, Jr.’s administration declared its intention to reverse course for yet a fourth time. See Safeguarding and Securing the Open Internet, 88 Fed. Reg. 76048 (2023); Brand X, 545 U. S., at 981–982. Each time, the government claimed its new rule was just as “reasonable” as the last. Rather than promoting reliance by fixing the meaning of the law, Chevron deference engenders constant uncertainty and convulsive change even when the statute at issue itself remains unchanged.

The day Loper Bright was issued, the 6th Circuit ordered the parties in the net-neutrality lawsuit to brief the court on the decision’s relevance to whether the court should stay the FCC order. With those briefs now submitted, let’s review the arguments.

The broadband providers argue that Loper Bright strengthens their case in several ways. They contend it reinforces the applicability of the “major questions doctrine,” which requires Congress to speak clearly when authorizing an agency to make decisions of vast economic and political significance. Regulating the internet as a public utility is clearly a major question, they argue, and Congress never “expressly” authorized the FCC to do so.

In contrast, the agency emphasizes that its order does not rely on Chevron deference (it’s mentioned only three times in the FCC’s order). Instead, the commission argues that the order represents its view of the “best reading” of the Communications Act, using the traditional tools of statutory interpretation.

This may be a weak argument. Loper Bright is clear that the final word on such “best readings” of statutes belongs to the courts:

The Administrative Procedure Act requires courts to exercise their independent judgment in deciding whether an agency has acted within its statutory authority, and courts may not defer to an agency interpretation of the law simply because a statute is ambiguous.

While the Court overruled Chevron, it embraced the older Skidmore “respect” for agency interpretations:

Perhaps most notably along those lines, in Skidmore v. Swift & Co., 323 U. S. 134 (1944), the Court explained that the “interpretations and opinions” of the relevant agency, “made in pursuance of official duty” and “based upon . . . specialized experience,” “constitute[d] a body of experience and informed judgment to which courts and litigants [could] properly resort for guidance,” even on legal questions. Id., at 139–140. “The weight of such a judgment in a particular case,” the Court observed, would “depend upon the thoroughness evident in its consideration, the validity of its reasoning, its consistency with earlier and later pronouncements, and all those factors which give it power to persuade, if lacking power to control.” Id., at 140.

The decision also notes:

The APA, in short, incorporates the traditional understanding of the judicial function, under which courts must exercise independent judgment in determining the meaning of statutory provisions. In exercising such judgment, though, courts may—as they have from the start—seek aid from the interpretations of those responsible for implementing particular statutes. Such interpretations “constitute a body of experience and informed judgment to which courts and litigants may properly resort for guidance” consistent with the APA. Skidmore, 323 U.S., at 140. And interpretations issued contemporaneously with the statute at issue, and which have remained consistent over time, may be especially useful in determining the statute’s meaning. See ibid.; American Trucking Assns., 310 U.S., at 549.

The FCC contends that it has expertise in “factual and technical issues” regarding which broadband services constitute telecommunications services or information services, giving its interpretations greater weight.

For their part, the broadband providers emphasize that the FCC’s current view is neither contemporaneous with the 1996 Telecommunications Act, nor has it been consistent over time. Indeed, even regarding purely factual and technical issues, the agency’s interpretation has been inconsistent.

The petitioners have a point here. For example, the broadband providers’ brief notes that, right after passage of the Telecommunications Act of 1996, the commission concluded that internet-access services constituted information services, because they “give[] users a variety of advanced capabilities.” The FCC’s latest brief, however, endorses the description of broadband service as a “dumb pipe.”

The broadband providers contend that, under Loper Bright, the Supreme Court’s 2005 Brand X decision upholding the classification of broadband as an “information service” should now be treated as binding “statutory precedent.” Their brief argues that the FCC has provided no basis for overcoming this precedent:

After Loper Bright, Brand X’s determination that it was “lawful” for the Commission to conclude that broadband Internet service is not a “telecommunications service” under the 1996 Act, id., is binding under statutory stare decisis. But here, the FCC is arguing that broadband Internet access service is a telecommunications service. Order ¶ 25. That argument necessarily implies that the statutory construction deemed lawful by the Supreme Court in Brand X is incorrect. The Order, however, provides no basis for overcoming stare decisis.

In contrast, the FCC argues that Brand X does not foreclose its current interpretation. It notes that Brand X merely held that classifying broadband as an information service was permissible under Chevron, not that it was the best or only permissible reading of the statute. The FCC contends that its current view better aligns with the original, contemporaneous understanding of the 1996 law.

This case could be tied up in the courts for years, and it’s not clear which way this court will go or how subsequent appeals will be judged. It is clear, however, that the Supreme Court is exasperated with the FCC’s flip-flopping between Title I and Title II. What we don’t know is whether the most recent flip was the last or if there will be one more. It’s yet another reminder that all of this could have been avoided if Congress had given clear guidance on the issue and settled the matter.