For those of who’ve been doing the Telecom Two-Step over the past year, the holiday break can’t come soon enough. Last week, comments were due on the Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC) latest proposal to impose Title II common-carrier regulation under the guise of net neutrality national security. Before that, we had the FCC’s new and expansive “digital discrimination” rules. Early in the New Year, we’ve got reply comments due on Title II and comments on the FCC’s proposal to ban early termination fees for cable and satellite providers.

The FCC has pushed telecom folks to crank out more content than James Patterson. So, we can be forgiven for pouring ourselves a cup of cheer, turning on “The Muppet Christmas Carol,” and taking a brief hiatus.

The Fraternal Twins: Title II and Digital Discrimination

Yet again, the FCC intends to reclassify broadband internet-access services under Title II of the Communications Act of 1934. Among the multitude of rules this move entails, the FCC would impose so-called “net neutrality” conditions by banning providers from blocking or throttling content and engaging in paid-prioritization practices.

If approved, the Title II rules would work hand-in-hand with the FCC’s sweeping digital-discrimination rules, which explicitly subject broadband pricing, discounts, incentives and other terms and conditions to scrutiny and enforcement. FCC Commissioner Brendan Carr has described Title II and digital discrimination as “fraternal twins.” While the FCC has been clear that it will not (for now) regulate rates under Title II, the agency’s digital-discrimination rules explicitly identify broadband pricing as subject to FCC scrutiny and enforcement.

In comments to the FCC, the International Center for Law & Economics (ICLE) note that some critics see the FCC’s pursuit of common-carrier regulation of broadband internet as an attempt to “control” an industry with vast economic and political significance. And that may be true. A more charitable criticism, however, is that the commission mistakenly believes that the provision of broadband internet is a natural monopoly best served by utility-style regulation.

Alternatively, it could be argued that the FCC mistakenly believes that a dynamic and competitive industry marked by rapid innovation, improving quality, and falling prices can be effectively regulated as if it were a public utility. Indeed, ICLE—along with many other commenters—point out that, despite several recent opportunities to regulate broadband internet under Title II, Congress never explicitly provided the FCC the authority to do so.

In particular, the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) was a perfect opportunity for Congress to legislate net neutrality or Title II regulation, if that’s what it wanted the FCC to do. The IIJA was the legislation that mandated the FCC to issue rules to prevent digital discrimination. It was also the legislation that allocated more that $42 billion to build out broadband infrastructure under the Broadband Equity, Access and Deployment (BEAD) program. Tellingly, Congress empowered the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) to implement BEAD, rather than the FCC. Mandating Title II classification would’ve taken less than a page of the 1,000+ page IIJA. Its omission can be seen as a clear sign that Congress—with Democratic majorities in both houses at the time—had little interest in such expansive regulatory intervention.

By most measures, U.S. broadband competition is vibrant and has strengthened dramatically since both the repeal of Title II rules in 2018 and the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

- More households are connected to the internet. The third iteration of the National Broadband Map, released in November 2023, indicates 94% of locations now have access to connections of 25/3 Mbps or higher and 89% have access to speeds of 200/25 Mbps or higher.

- More households are served by more than a single provider.

- In 2018, 73.0% of households had access to 25/3 Mbps speeds from only one or two fixed broadband providers, and only 21.6% had access from three or more providers.

- In 2021, only 29.1% of households had access from one or two providers while 69.3% were served by three or more providers.

- Thus, the number of households served by three or more providers increased by 47.7 percentage points from 2018 through 2021.

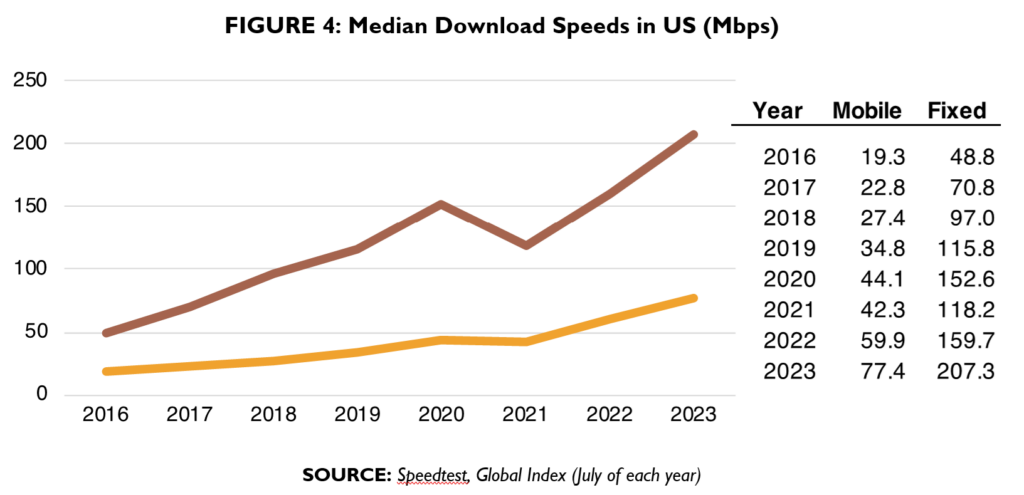

- Broadband speeds have increased, while prices have declined. A broadband-pricing index published by USTelecom reports that inflation-adjusted broadband prices for the most popular speed tiers have fallen 54.7% from 2015 to 2023, for an average drop of 5.6% a year. The Producer Price Index for residential internet-access services fell by about 12% since 2015. The median fixed-broadband connection in the United States now delivers more than 207 Mbps download service, an 80% increase over the pre-pandemic median speed.

- New technologies—such as satellite and 5G—have expanded internet access and intermodal competition among providers.

- Citing estimates from research firm Omdia, the Wall Street Journal reports that about 43% of U.S. consumers had 5G mobile subscriptions as of June 2023.

- Gregory Rosston and Scott Wallsten conclude: “Starlink (and its likely future LEO competitors) are creating real, facilities-based broadband competition in areas that are currently not served by low-latency service or are served only by companies that rely on heavy subsidies. The opportunities, therefore are broadband competition in rural areas and large reductions in taxpayer spending on broadband availability.”

A Major Question?

With apologies to Frank Loesser and Ella Fitzgerald:

Ah, but in case I stand one little chance,

Here comes the major question in advance.

Will Title II be an MQ, MQD?

Oh, will it be an MQ, MQD?

A big question—some would say a major question—regarding the FCC’s latest attempt at Title II classification is: Can they do it?

Under what is now known as the “major questions doctrine” or “MQD,” the U.S. Supreme Court has said: “We expect Congress to speak clearly if it wishes to assign to an agency decisions of vast ‘economic and political significance.’” That is, the MQD requires that Congress give an agency clear congressional authorization to act in such cases. In other words, an ambiguous grant of authority is not enough.

In their comments to the FCC, Gus Hurwitz and Christopher Yoo conclude that the FCC itself seems to think that Title II regulation is a major question of “economic and political significance”:

Rather, the fact that an agency feels it is necessary to ask whether its decisions raise major questions suggests that those questions may well be major. This alone should give the agency pause about taking such decisions—especially in an era of intense judicial scrutiny of agency action it would be a curious decision for any agency to instead seek to structure its decisions so as to avoid the appearance of their having vast economic or political significance. [emphasis added]

In addition, Hurwitz & Yoo note:

The vast significance of the proposed rules cannot be overstated—though the NPRM seems notably to attempt to understate it. Discussing broadband in 2015, former Chair Tom Wheeler described the Internet as “the most powerful network in the history of mankind.” This was echoed in the 2015 Open Internet Order. The first sentence of the 2015 Order asserted that “[t]he open Internet drives the American economy and serves, every day, as a critical tool for America’s citizens to conduct commerce, communicate, educate, entertain, and engage in the world around them.” Similarly, the NPRM for that Order began with: “The Internet is America’s most important platform for economic growth, innovation, competition, [and] free expression . . . . [It] has been, and remains to date, the preeminent 21st century engine for innovation and the economic and social benefits that follow.” [emphasis added, citations omitted]

Thus, ICLE’s comments conclude, (1) the major questions doctrine is now clearly recognized by the Supreme Court, (2) the decision to apply Title II to broadband services is a decision of “vast economic and political significance” under the MQD, and (3) the Court’s Brand X decision found that the Communications Act is ambiguous as to whether broadband is a “telecommunications service.” As such, the decision to reclassify broadband service again will likely fail under the MQD.

Happy Holidays, Hootenanniers. We’ll see you in the New Year for more telecom-policy shenanigans.