In a recent guest essay for The New York Times, Aaron Klein of the Brookings Institution claims that the merger between Capital One and Discover would “keep intact the broken and predatory system in which credit card companies profit handsomely by rewarding our richest Americans and advantaging the biggest corporations.”

That’s quite an indictment! Fortunately, Klein also offers solutions. Phew!

But really, it’s difficult to understand how someone could describe the highly innovative, dynamic, and efficient U.S. credit-card system as “broken.” If it were, why would U.S. credit-card networks like Visa, Mastercard, American Express, and Discover be the world leaders, accounting for more than 60% of global market share?

And far from being “predatory,” credit cards have been hugely valuable to American families at all income levels. During the pandemic, they literally saved lives by enabling people in lockdown to buy food online and have it delivered to their homes. As Klein himself notes:

The pandemic changed how we buy things, significantly increasing the share of transactions put on credit cards rather than conducted in cash.

Klein tries to turn this positive into a negative, noting that the increase in card use added “to the swipe fees merchants pay.” What he fails to mention is that the switch from cash to credit has, in general, reduced merchants total costs because the costs of handling cash are so much higher. When a customer pays in cash, checkout takes longer than paying with a card (especially where the transaction is contactless). For larger stores, that means more cash-register operators must be hired. For smaller stores, it means there are less resources available to perform other tasks, such as taking inventory or restocking shelves.

Cash also presents a greater risk of theft, which means merchants must invest in security systems both in-store and for moving cash to the bank. And cash must be counted and deposited, both of which take time.

Study after study has shown that, when all relevant costs are taken into account, cash costs merchants more than payment cards. A 2018 study by the IHL Group, for example, found that the cost of accepting cash averaged about 9% and ranged from 4.7% for larger grocery stores to 15.5% for bars and restaurants. By contrast, the all-in cost of processing credit-card payments is typically less than 3%.

Klein’s sources don’t inspire much confidence. The link in his opening paragraph is not to an academic study, but to a video on the Times’ own website that spins an elaborate tale of how a frying pan bought using credit-card rewards was actually paid for by MJ, the owner of a local convenience store. In essence, the video asserts that, by using a rewards credit card to buy $100 of goods every week for a year at MJ’s store, enough rewards were accrued to pay for the frying pan.

Let’s suppose that the bank that issued the rewards card charged the maximum interchange fee on the transactions at MJ’s store, which in 2023 was 3.15%. Further assume that MJ’s merchant-account provider charges her on an “interchange-plus” basis. If MJ used Helcim, she would pay the interchange fee plus 0.4%, plus $0.08 per transaction.

So, of the $5,200 spent over the course of the year by the customer using a rewards card, $163.80 would go to the issuing bank and $28.80 to Helcim, leaving MJ with a net of $5,007.40. By contrast, if MJ had been paid in cash, she would have a net of $4,768.4 (based on the average costs identified by IHL for convenience stores of 8.3%).

While the Times video wants our hearts to bleed for MJ having to pay for a customer’s All-Clad D5 12” frying pan, had the customer paid her in cash instead, she would have made $239 less. And the customer would have been less happy, because he would have effectively paid about $250 more (the cost of the pan). In other words, paying with cash would make the merchant and the consumer worse off to the tune of nearly $500.

Credit cards also have other benefits that Klein ignores in his simplistic story. By providing credit—including up to 45 days interest free for cardholders who pay off their balance each month—credit cards enable people to smooth their spending so that they can buy items even when they don’t have money in the bank. They also provide fraud and theft protection for the cardholder, making it far less risky to carry a card than a bundle of cash. Many cards also include payment-protection insurance, rental-car insurance, and travel insurance.

Finally, credit cards make it far easier to trace payments, because the card issuer knows the identity and address of the legitimate user. This makes it more difficult to make illegal purchases using credit cards (compared to relatively untraceable cash) and easier to enforce sales taxes.

This highlights a fundamental problem with Klein’s analysis: he counts the costs of paying with credit cards but fails to explain for what would happen in the alternative. He wants us to believe that:

the rest of us, whether we pay with cash, a debit-card or a middle-of-the-road credit card, wind up paying more—because we are subsidizing these rewards cards for whom only the wealthiest qualify.

Except that’s just not true.

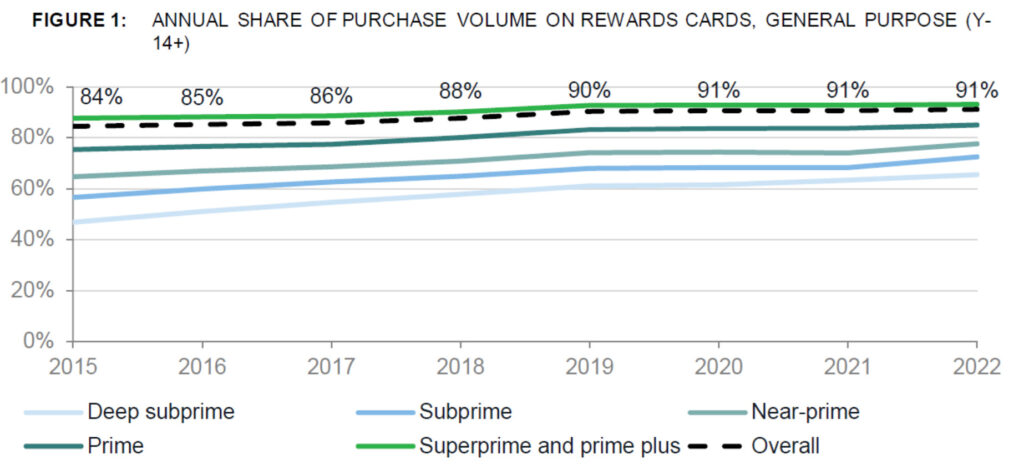

First, as noted, in most cases, cash purchases are more costly for store owners, so credit-card users are subsidizing cash users. Second, as Todd Zywicki, Ben Sperry, and I have noted, and as can be seen in the figure below from the most recent Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) report on the consumer credit-card market, access to rewards credit cards is less a function of income and more a function of the cardholder’s credit score. Third, as the figure also shows, more than 90% of all credit-card transactions are made using rewards cards.

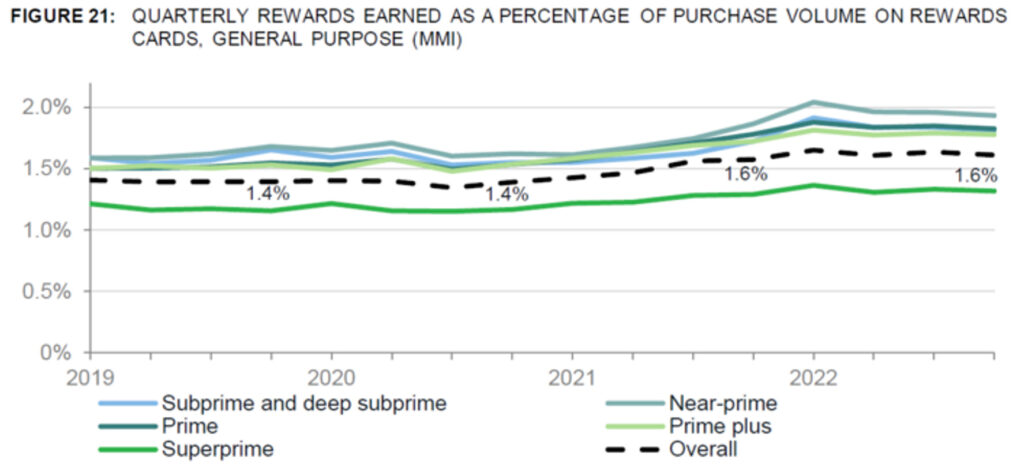

Fourth, as can be seen in the chart below, and as the CFPB noted in the accompanying text: “Earning rates are about the same across credit score tiers for those with rewards cards, except for consumers with scores above 800.” Perhaps Mr. Klein does not have access to those higher-value rewards cards, but if so, he is the exception, not the rule.

These data suggest that, for all the critics’ bluster, the value of rewards per dollar spent varies relatively little from card to card; what differs is the types of rewards and other associated benefits. Innovations along these lines have been important drivers in the shift from cash and checks to credit cards, with attendant benefits for consumers, merchants, and society as a whole.

Nonetheless, Klein is correct that the fees charged for different cards can vary significantly. In fact, importantly, the story is rather more complicated than Klein makes out. Interchange fees typically vary not only by card, but also by type of merchant. This is, at least in part, because different merchants pose different risks of fraud and chargeback.

Moreover, in contrast to Klein’s assertion that low-dollar sales typically have high fees, networks often discount the fees on small-ticket items in order to encourage adoption. For transactions of $15 or less, Visa’s small-ticket interchange fee for credit cards carries no fixed-fee component. For transactions of $5 or less, Mastercard’s fixed fee is only $0.04. And in some cases, such as for gasoline purchases, they cap the total amount (for example, Mastercard charges a maximum of $0.95 and Visa a maximum of $1.10 for gas).

Nonetheless, Klein offers the anecdote that, one year, his “oldest friend’s small coffee shop paid more in card processing costs than for coffee beans.” In fairness, the coffee shop in question, Bump n Grind in Maryland, roasts its own beans, and therefore buys green beans that are considerably less expensive than pre-roasted beans. It also sells much more than just coffee, including vinyl records. So it probably has many costs that are higher than the amount it pays for beans, including: rent, equipment, utilities, and staff.

It may also use a merchant acquirer or a payment gateway (such as Square or Stripe) that offers blended rates (that is, a single rate for all transactions regardless of the type of card or size of transaction), which would mean that it is unable to take advantage of the small-ticket discount available on “interchange-plus” plans.

‘Solutions’ Far Worse Than the ‘Problem’

Klein lays much of the blame on the U.S. Supreme Court for the alleged problem of consumers being charged different swipe fees for different cards issued on the same payment network. He claims that “a 2018 Supreme Court ruling effectively forces merchants to accept either every type of card – from, say, a basic Green Card to the Platinum Card – from an issuer like Amex or none of them.” And he goes on to assert that “the ruling also barred merchants from incentivizing consumers to use cheaper ones.”

There’s just one problem with these claims: they’re not true.

What the Supreme Court did in Ohio v. Amex was to prevent the state from overriding the contractual “anti-steering” provisions that had long been established by credit-card networks in their agreements with merchants (either directly, in the case of three-party cards such as Amex and Discover, or via agreements with issuers, in the case of four-party cards like Visa and Mastercard). The Court explained its rationale clearly:

Respondent… Amex… operate[s] what economists call a “two-sided platform,” providing services to two different groups (cardholders and merchants) who depend on the platform to intermediate between them. Because the interaction between the two groups is a transaction, credit-card networks are a special type of two-sided platform known as a “transaction” platform. The key feature of transaction platforms is that they cannot make a sale to one side of the platform without simultaneously making a sale to the other. Unlike traditional markets, two-sided platforms exhibit “indirect network effects,” which exist where the value of the platform to one group depends on how many members of another group participate. Two-sided platforms must take these effects into account before making a change in price on either side, or they risk creating a feedback loop of declining demand. Thus, striking the optimal balance of the prices charged on each side of the platform is essential for two-sided platforms to maximize the value of their services and to compete with their rivals.

Visa and MasterCard—two of the major players in the credit-card market—have significant structural advantages over Amex. Amex competes with them by using a different business model, which focuses on cardholder spending rather than cardholder lending. To encourage cardholder spending, Amex provides better rewards than the other credit-card companies. Amex must continually invest in its cardholder rewards program to maintain its cardholders’ loyalty. But to fund those investments, it must charge merchants higher fees than its rivals. Although this business model has stimulated competitive innovations in the credit-card market, it sometimes causes friction with merchants. To avoid higher fees, merchants sometimes attempt to dissuade cardholders from using Amex cards at the point of sale—a practice known as “steering.” Amex places antisteering provisions in its contracts with merchants to combat this.

While these anti-steering provisions are important, they are not the provisions to which Klein refers, which are known as “honor-all-cards” provisions and which prevent merchants from discriminating against cards bearing the network’s brand. Nonetheless, honor-all-cards provisions are likewise important to the functioning of two-sided payment networks (as Nobel laurate economist Jean Tirole has noted) because they enable card networks to create a range of offerings, thereby facilitating innovation by and competition among issuers.

Without the honor-all-cards provisions, merchants might refuse to accept cards with higher interchange fees. Klein seems to think this is a good idea. He proposes that:

Congress should legislatively correct the Supreme Court’s mistake. For starters, give merchants the power to reject the priciest credit cards, and let’s see if their users are willing to pay the true cost of their rewards.

But this would result in a race to the bottom in which card issuers were unable to offer rewards or otherwise differentiate their products, leading to a decline in the use of cards. This, in turn, would reduce spending, harming both consumers and merchants.

Klein supports his argument that Congress could override the honor-all-cards provision by citing the Durbin amendment, which imposed price controls on debit-interchange fees. A recent study by Vladimir Mukharlyamov of Georgetown University and Natasha Sarin of the University of Pennsylvania found that this had the effect of reducing covered banks’ annual revenues by about $5.5 billion. Seeking to recoup some of the lost revenue, banks on average doubled their monthly fees on checking accounts; increased the minimum deposit required for “free” checking by 21%; and reduced the availability of accounts with no-minimum free checking by about half.

Likely as a direct consequence, hundreds of thousands of the poorest Americans left the banking system altogether. Meanwhile, merchants passed through little, if any, of the savings resulting from the reduced debit-interchange fees, so those on low incomes who kept their accounts but paid monthly fees were measurably worse off.

To make matters worse, Klein wants “brave policymakers” to “start taxing reward points.” At least he is clear that this is really just about taxing the rich:

The richer you are, the more likely you qualify for bigger rewards. Progressive taxation rates mean that exempting rewards from taxation makes them nearly four times as valuable to those in the top tax bracket as the bottom.

As it happens, some credit-card rewards probably are taxable; it depends on their function. But if policymakers were to make all rewards taxable, it would harm those that function primarily as rebates and loyalty incentives—such as airline miles received on co-branded cards. And that, in turn, would harm the co-brand partners, such as airlines and hotels.

Klein’s final proposal is more troubling. He suggests that “we could require all merchants have access to the same swipe-fee pricing, regardless of size.” His concern here is that some larger merchants leverage their bargaining power to obtain lower interchange fees. In part, larger merchants benefit from economies of scale and can implement transaction monitoring and security systems that smaller merchants simply can’t afford.

Meanwhile, a few large merchants (such as Costco) operate membership-based systems that enable them to forego customer convenience and strike exclusive deals with specific card issuers and networks, thereby obtaining lower swipe fees. Neither of these apply to individual smaller merchants, so the suggestion that swipe fees could be reduced by mandate to the levels negotiated by larger merchants is totally unrealistic.

In his last few paragraphs, Klein returns to the merger between Capital One and Discover, the hook around which he has hung a series of shibboleths about credit cards that he uses as the premise for his terrible policy proposals. And here again, he repeats those shibboleths, moaning that:

Capital One already seems to be competing with American Express for wealthy customers who like elite airport lounges and bit travel perks …

And in the next paragraph:

As the economy continues to digitize with more micropayments, the credit card burden will keep growing, particularly on smaller businesses.

And in the final paragraph:

Until legislators are willing to change the system that showers tax-free rewards on the upper middle class, the cash register will continue to exacerbate the wealth gap.

What utter tosh.