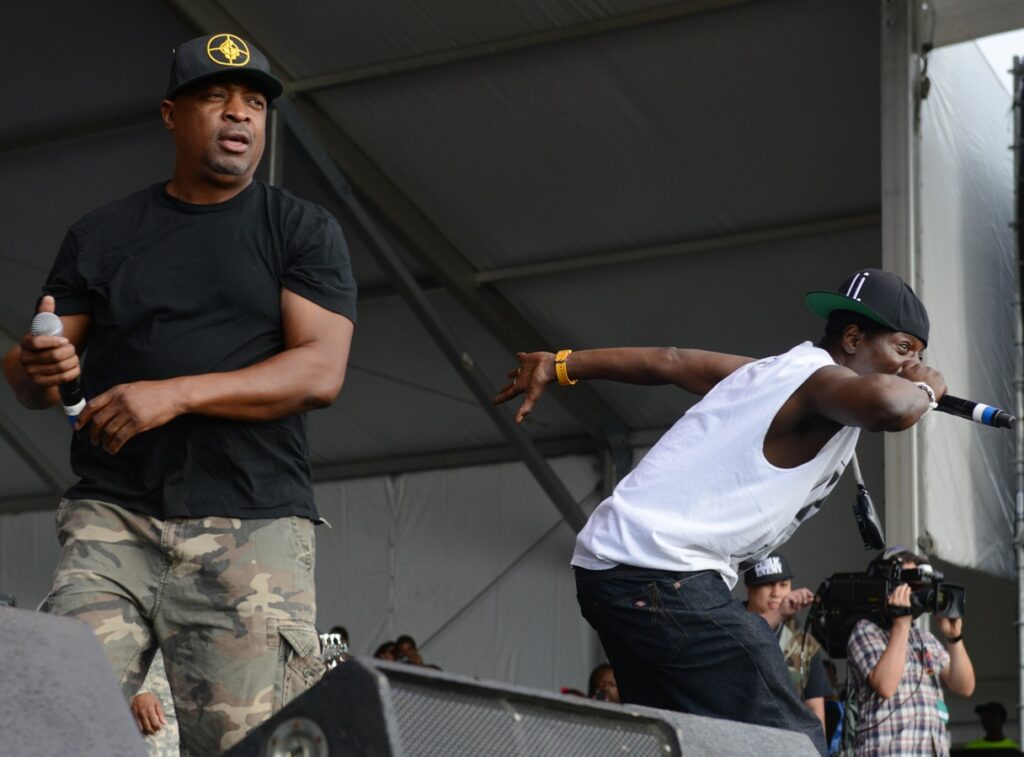

As in the Public Enemy song that gives this post its title, the hype about alleged competition risks in the artificial intelligence (AI) “market” is a sequel—and not a good one—to the hyperbolic and dystopian view that has informed several recent antitrust-policy proposals and demands for tougher enforcement of competition laws, particularly in digital markets. As we will explain, the evidence tells a different story, and there are plenty of reasons to be rather cautious before taking any action in the AI sector.

Geoff Manne and Dirk Auer explain what we mean by the dystopian view of antitrust:

antitrust pessimists have set their sights predominantly on the digital economy—“big tech” and “big data”—alleging a vast array of potential harms. Scholars have argued that the data created and employed by the digital economy produces network effects that inevitably lead to tipping and more concentrated markets. In other words, firms will allegedly accumulate insurmountable data advantages and thus thwart competitors for extended periods of time. Some have gone so far as to argue that this threatens the very fabric of western democracy.

Now that AI and generative AI have garnered massive attention—particularly since the release of ChatGPT in November 2022—competition authorities are rushing to be the first to intervene, or at least to “say something” about these emerging markets. In a recent consultation, the European Commission asked: “What is the role of data and what are its relevant characteristics for the provision of generative AI systems and/or components, including AI models?”

Unsurprisingly, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has likewise been hypervigilant about the risks ostensibly posed by incumbents’ access to data. In comments submitted to the U.S. Copyright Office, for example, the FTC argued that: “(t)he rising importance of AI to the economy may further lock in the market dominance of large incumbent technology firms. These powerful, vertically integrated incumbents control many of the inputs necessary for the effective development and deployment of AI tools, including cloud-based or local computing power and access to large stores of training data.”

Likewise, in a conference about competition in AI markets co-organized by the U.S. Justice Department (DOJ) and the Stanford Graduate School of Business, Assistant U.S. Attorney General for Antitrust Jonathan Kanter claimed that:

Powerful networks and feedback effects may enable dominant firms to control these new markets, and existing power in the digital economy may create a powerful incentive to control emerging innovations that will not only impact our economy, but the health and well-being of our society and free expression itself.

On a more hyperbolic note, Andreas Mundt, the head of Germany’s Federal Cartel Office, called AI a “first-class fire accelerator” for anticompetitive behavior and argued it “will make all the problems only worse.” He further argued that “there’s a great danger that we’ll get an even deeper concentration of digital markets and power increase at various levels, from chips to the front end.” And Mundt appears to be just one of a number of prominent policymakers who believe that AI markets will enable incumbent tech firms to further entrench their market positions.

These “concerns” prompted a joint statement from the FTC, the DOJ, the European Commission, and the United Kingdom’s Competition and Market Authority (CMA) in which, while acknowledging that “(a)t their best, these technologies could materially benefit our citizens, boost innovation and drive economic growth,” the agencies insist upon “being vigilant and safeguarding against tactics that could undermine fair competition.” The statement highlighted three primary risks to competition, summarized below:

- Concentrated control of key inputs that potentially could put a small number of companies in position to exploit existing or emerging bottlenecks across the AI stack.

- Entrenching or extending market power in AI-related markets: large incumbent digital firms that already enjoy strong accumulated advantages could use these to protect themselves against AI-driven disruption. This, in turn, may allow such firms to extend or entrench their positions to the detriment of future competition.

- Arrangements involving key players could amplify risks. Major firms could use partnerships, financial investments, and other connections among firms related to the development of generative to undermine or co-opt competitive threats and steer market outcomes in their favor at the expense of the public.

To be sure, it makes sense that the largest online platforms—including Alphabet, Meta, Apple, and Amazon—should have a meaningful advantage in the burgeoning markets for generative-AI services. After all, it is widely recognized that data is an essential input for generative AI. This competitive advantage should be all the more significant given that these firms have been at the forefront of AI technology for more than a decade. Over this period, Google’s DeepMind and AlphaGo and Meta’s NLLB-200 have routinely made headlines. Apple and Amazon also have vast experience with AI assistants, and all of these firms deploy AI technologies throughout their platforms.

Contrary to what one might expect, however, the tech giants have, to date, been largely unable to leverage their vast troves of data to outcompete startups like OpenAI and Midjourney. At the time of writing, OpenAI’s ChatGPT appears to be, by far, the most successful large language model (LLM) chatbot, despite the large tech platforms’ apparent access to far more (and more up-to-date) data.

Moreover, it is important not to neglect the role that open-source models currently play in fostering innovation and competition. As former DOJ Chief Antitrust Economist Susan Athey pointed out in a recent interview, the AI industry “may be very concentrated, but if you have two or three high quality — and we have to find out what that means, but high enough quality — open models, then that could be enough to constrain the for-profit LLMs.” Open-source models are important because they allow innovative startups to build upon models already trained on large datasets—therefore entering the market without incurring that initial cost. Apparently, there is no lack of open-source models, since companies like xAI, Meta, and Google offer their AI models for free (see, for instance, here and here).

It is understandable that, in light of the meteoric rise of consumer-facing AI services, competition enforcers and policymakers want to know and understand more about them. They “must do something” about AI. But the AI revolution should also be an opportunity to revisit some priors. As we’ll explain below, the rapid emergence of generative-AI technology may undercut many core assumptions of today’s competition-policy debates, which have focused largely on the rueful after effects of the purported failure of 20th century antitrust to address the allegedly manifest harms of 21st century technology. These include the notions that data advantages constitute barriers to entry and can be leveraged to project dominance into adjacent markets, and that scale itself is a market failure to be addressed by enforcers.

We address these notions in our recent remarks to a DOJ invitation to comment on promoting competition in AI. Proponents of more extensive antitrust intervention into digital markets often cite data-network effects as a source of competitive advantage and barrier to entry, arguing that: “the collection and use of data creates a feedback loop of more data, which ultimately insulates incumbent platforms from entrants who, but for their data disadvantage, might offer a better product.” This self-reinforcing cycle, so the story goes, leads to market domination by a single firm.

But it is important to note the conceptual problems these claims face. Because data can be used to improve products’ quality and/or to subsidize their use, if possessing data constitutes an entry barrier, then any product improvement or price reduction made by an incumbent could be problematic. This is tantamount to an argument that competition itself is a cognizable barrier to entry.

Of course, it would be a curious approach to antitrust if competition were treated as a problem, as it would imply that firms should under-compete—i.e., should forego consumer-welfare enhancements—in order to inculcate a greater number of firms in a given market, simply for its own sake. Actual economic studies of data-network effects, however, have been few and far between, with scant empirical evidence to support such a story (see Geoff and Dirk here for a review of the literature on increasing returns to scale in data).

As we have mentioned, “big tech” is not currently leading the AI race, with ChatGPT accounting (as of June 2024) for almost 69.9% of the market share of “AI tools.” The picture is similar in the field of AI image generation. As of August 2023, Midjourney, Dall-E, and Stable Diffusion appeared to be the three market leaders in terms of user visits. This is despite competition from the likes of Google and Meta, who arguably have access to unparalleled image and video databases by virtue of their primary platform activities (see here and here).

How have these AI upstarts managed to be so successful? Is their success just a flash in the pan before Web 2.0 giants catch up and overthrow them? It is too early to answer these questions, but the success of these start-ups allows us to make some observations.

To start, data can have diminishing marginal returns. In other words, past a certain point, acquiring more data does not confer a meaningful edge to the acquiring firm. As Catherine Tucker put it, following a review of the literature: “Empirically there is little evidence of economies of scale and scope in digital data in the instances where one would expect to find them.” Likewise, following a survey of the empirical literature on this topic, Geoff and Dirk concluded that:

Available evidence suggests that claims of “extreme” returns to scale in the tech sector are greatly overblown. Not only are the largest expenditures of digital platforms unlikely to become proportionally less important as output increases, but empirical research strongly suggests that even data does not give rise to increasing returns to scale, despite routinely being cited as the source of this effect.

In other words, being the firm with the most data appears to be far less important than having enough data. Moreover, this lower bar may be accessible to far more firms than one might initially think possible. Furthermore, obtaining sufficient data could become easier still—that is, the volume of required data could become even smaller—with technological progress. For instance, synthetic data may provide an adequate substitute to real-world data for AI applications (see here), or may even outperform real-world data (see here). As Thibault Schrepel and Alex Pentland surmise:

[A]dvances in computer science and analytics are making the amount of data less relevant every day. In recent months, important technological advances have allowed companies with small data sets to compete with larger ones.

Indeed, past a certain threshold, acquiring more data might not meaningfully improve an AI service, where other improvements (such as better training methods or data curation) could have a large impact. In fact, there is some evidence that excessive data impedes a service’s ability to generate results appropriate for a given query. As pointed out by Igor Susmeli: “[S]uperior model performance can often be achieved with smaller, high-quality datasets than massive, uncurated ones. Data curation ensures that training datasets are devoid of noise, irrelevant instances, and duplications, thus maximizing the efficiency of every training iteration.”

The bottom line is that data is not the be-all and end-all that many in competition circles make it out to be. While data may often confer marginal benefits, there is little evidence that these benefits are ultimately decisive. As a result, incumbent platforms’ access to vast numbers of users and troves of data in their primary markets might only marginally affect their competitiveness in AI markets.

A second important observation is that, in those instances where it is valuable, data does not just fall from the sky. Instead, it is through smart business and engineering decisions that firms can generate valuable information (which does not necessarily correlate with owning more data). For instance, OpenAI’s success with ChatGPT is often attributed to its more efficient algorithms and training models, which arguably have enabled the service to improve more rapidly than its rivals (see, for instance here and here).

The attentive reader, of course, will retort that while the internet giants may not be leading the race in generative AI, they are using minority investments and partnerships to “undermine or co opt competitive threats and steer market outcomes in their favour at the expense of the public,” as mentioned in the competition agencies’ joint statement. But as we pointed out in our response to the CMA’s recent invitation to comment on partnerships and other arrangements involving artificial AI:

…these partnerships all involve the acquisition of minority stakes that do not entail any change of control over the target companies. Amazon, for instance, will not have “ownership control” of Anthropic. The precise amount of shares acquired has not been made public, but a reported investment of $4 billion in a company valued at $18.4 billion does not give Amazon a majority stake or sufficient voting rights to control the company or its competitive strategy. It has also been reported that the deal will not give Amazon any seats on the Anthropic board or special voting rights (such as the power to veto some decisions). There is thus little reason to believe Amazon has acquired indirect or de facto control over Anthropic.

Microsoft’s investment in Mistral AI is even smaller, in both absolute and relative terms. Microsoft is reportedly investing only $16 million in a company valued at $2.1 billion. This represents less than 1% of Mistral’s equity, making it all but impossible for Microsoft to exert any significant control or influence over Mistral AI’s competitive strategy. Likewise, there have been no reports of Microsoft acquiring seats on Mistral AI’s board or special voting rights. We can therefore be confident that the deal will not affect competition in AI markets.

Much of the same applies to Microsoft’s dealings with Inflection AI. Microsoft hired two of the company’s three founders (which currently does not fall under the scope of merger laws), and also paid $620 million for nonexclusive rights to sell access to the Inflection AI model through its Azure Cloud. Admittedly, the latter could entail (depending on deal’s specifics) some limited control over Inflection AI’s competitive strategy, but there is currently no evidence to suggest this will be the case.

None of these deals, on the other hand, entail any competitively significant behavioral commitments from the target companies. There are no reports of exclusivity agreements or other commitments that would restrict third parties’ access to these firms’ underlying AI models.

Paradoxically, overenforcement in the field of generative AI could engender the very harms that policymakers currently seek to avert. Indeed, preventing so-called “big tech” firms from competing in these markets (for example, by threatening competition intervention as soon as they build strategic relationships with AI startups) may thwart an important source of competition needed to keep today’s leading generative-AI firms in check.

In short, competition in AI markets is important, but trying naïvely to hold incumbent (in adjacent markets) tech firms back, out of misguided fears they will come to dominate this space, is likely to do more harm than good.

To be clear, nothing in this post is meant to suggest that there cannot be competition issues or anticompetitive conducts in “AI markets.” But it should take more than hypothetical risks to advance enforcement actions that could consume valuable resources of both agencies and competitors.

Listen to the evidence and don’t believe the hype.