While last year’s labor disputes between the Writers Guild of America (WGA) and the Screen Actors Guild (SAG-AFTRA), on the one hand, and Hollywood’s major movie and television studios, on the other, have been settled for months now, lingering questions remain about competitive conditions in the industry.

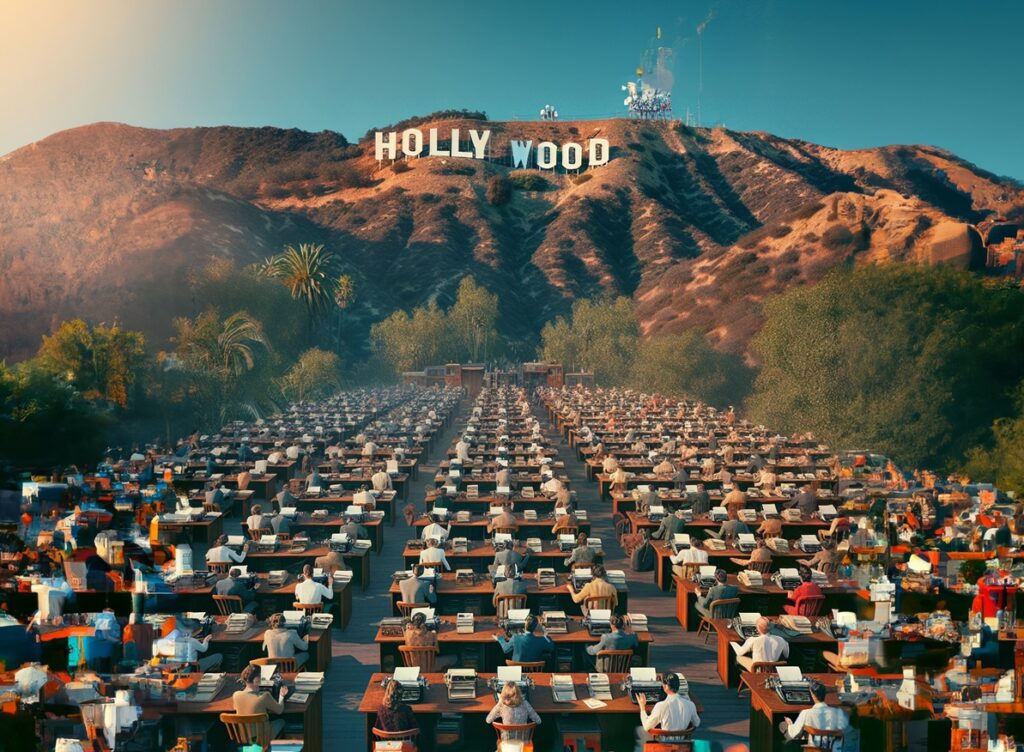

In a recent submission to the California Law Revision Commission—currently undertaking a project to review California antitrust law—the Writers Guild of America West (WGAW) presented a 55-page document outlining the guild’s concerns about media-industry consolidation and alleged harms to workers. The WGAW submission followed the WGA’s earlier report, “The New Gatekeepers,” which argued that companies like Disney, Amazon, and Netflix are poised to exert a stranglehold on the industry and systematically harm the talent they employ. Together, these reports paint a dire picture of media-industry consolidation and alleged worker exploitation.

In reality, however, their claims fundamentally mischaracterize the current state of the streaming market, and fail to appreciate the dynamic, competitive nature of this rapidly evolving industry.

An Industry in Flux

The media industry revolves around two basic activities: creating content and providing consumers access to content. Evaluating the state of the industry’s competitiveness therefore must start with an evaluation of how much content there is and how accessible it is. On any measure, both have skyrocketed.

The WGAW’s claims of constrained supply and market domination by a few players are unsupportable in the face of today’s content explosion. And this unprecedented proliferation of content is available to consumers not only in theaters and on cable networks, but also across multiple online streaming platforms and digital-distribution services. The real competition question is whether more content is available to viewers, and the answer—to anyone paying attention—is an unequivocal yes.

Despite these platforms’ ubiquity, however, monetization of content remains a serious challenge. As media analyst Doug Shapiro has put it:

No one really knows what the “steady-state” margins will be on the streaming video business and no one knows the equilibrium point in the transition…. Any precise forecast of industry profits is an educated guess, at best. But the unavoidable answer is that the total profit pie will be smaller.

The lack of profit (from which WGAW members seek a greater share of rents) is not a symptom of some malicious plot to exploit writers; it’s a product of an industry in flux. Indeed, it’s an industry in which, at root, there is too much content, too readily accessible to users, to adequately provide all the current players positive returns on the enormous investments required to produce and distribute that content. For that reason, as The New York Times‘ John Koblin notes, the amount of new television content—while still incredibly high—has dropped recently.

The drop is a result of broader reckoning inside the entertainment industry. For years, television executives tossed off billions of dollars on TV series to help build out their streaming services and chase subscribers. The spending has been a boon to high-profile writers and producers, who captured eight- and nine-figure deals, as well as for the actors, directors and behind-the-scenes workers who kept the engine going.

Viewed against the industry’s recent (but unsustainable) peak, the fortunes of some creatives may be waning. But this blinkered view belies the WGAW’s myopic understanding of the market’s evolution, which understandably has been focused primarily on the short-term effects on WGAW members. It not only misrepresents the current landscape, but also fails to recognize the current state of the industry as a natural stage in its ongoing transformation. The challenges faced by certain pieces of the supply chain don’t indicate the process is heading in an unfavorable direction; rather, they’re symptomatic of an industry in flux.

Over the history of media, various entities have been labeled “gatekeepers”—from vertically integrated studios owning theaters, to network broadcasters, to cable operators. But independent producers have always emerged, creating award-winning and high-demand content. Today’s streaming era is no different, and the industry’s current turmoil represents another shift, not a consolidation of power.

Indeed, to some extent, creators and distributors are victims of their own success, with increased supply affecting upstream producers and creators, at least for the time being. It will be crucial to remain patient as the industry evolves into a new equilibrium.

The Rise of Streaming…

The rise of streaming has dramatically altered how people consume video content, with streaming itself a highly competitive component of the media landscape. Consumers now have access to an unprecedented array of content through services like Netflix, YouTube, Disney+, Max, and many others. This proliferation of options has led more content to be produced, more diverse voices to be heard, better consumer access to legacy content, and more competitive pricing for consumers.

In contrast, the WGAW’s submission to the California Law Revision Commission paints a bleak picture of the streaming industry’s future. It predicts a market dominated by just three major streaming services—the titular “gatekeepers” of its report—resulting in steep price increases for consumers and exploitation and diminished wages for writers and other creatives.

This prophesied structural shift and its attendant consequences are far from inevitable. While it is likely that the number of competing online providers will have to shrink in order for any of them to be profitable, such changes alone wouldn’t mean an artificially limited supply of content or less access for consumers.

Nor does the shift to streaming automatically equate to competitive harms for writers, actors, or even independent producers at the hands of empowered streamers. Streaming services have been investing massively in content creation (both purchased from independent production companies and those features and series they produce themselves), often at a loss. Meanwhile, independent producers continue to thrive and are themselves consolidating—both a nod to the industry’s economic realities, as well as a development that will inevitably provide a check on whatever power the large studios and distribution services might wield.

The reason that Netflix—often cited as the market’s dominant—shifted to focus on in-house content production and the acquisition of independent producers was not to mistreat writers, but to stay viable in a highly competitive market. In fact, Netflix continues to license content from others, including giving new life to shows like Suits, to complement its original programming. Even Netflix’s decision to invest in its own content was originally initiated to remain competitive with cable and continues now in order to compete with other streaming services.

Moreover, investment in content production remains impressively high. And the diversity of content has expanded, due largely to the global reach of streaming platforms, providing consumers with more choices and greater access to niche, foreign, and otherwise unavailable content. Such a dramatic increase in the sources of content obviously may increase competition for U.S. writers and producers, but it is the opposite of a competitively constrained market.

…And Its Precarious Future

The backdrop for all of this is an industry in which massive investment has always been required to keep up with consumer demand and stave off competitors, but where returns on that investment are exceptionally difficult to realize. As one analyst put it about Disney’s streaming strategy:

Disney spent more than $500 million just on Marvel’s Moon Knight, Secret Invasion, and Loki Season 2 streaming series which were essentially given away free to Disney+ subscribers along with all the other content.

There are certainly copious benefits (especially for consumers) from the streaming model, but it is not without significant impediments.

The WGAW’s assertion that streaming services would wield unchecked “pricing power,” enabling them to implement substantial price increases without consequence, has been contradicted by market realities. Netflix’s recent attempts to raise prices were met with considerable consumer resistance, leading to higher churn rates and a notable increase in subscription cancellations. In fact, cancellations among users with multiple streaming subscriptions have risen by 25%.

This volatility in the subscriber base demonstrates the market’s competitiveness, as well as consumers’ willingness to switch or cancel services in response to price changes. Furthermore, the proliferation of ad-supported streaming options is a clear indication that providers recognize both consumers’ price sensitivity and the streaming business’s narrow profit margins.

At the same time, piracy is always in the background when it comes to digital-video distribution. Streaming presents an opportunity to ensure that monetization is possible for creators and distributors in a 21st-century environment where mass piracy is an ever-present threat. As soon as a movie is released in digital format (and sometimes even before it is released) it will be pirated and made available online. A viable distribution model must be both extremely convenient and reasonably priced in order to make free access to pirated videos online the second-best option for consumers. This puts serious constraints on how much rent is generated and how those rents can be divided.

And it’s not just from consumers that these alleged “gatekeepers” face constraints. The recent dispute between Charter Communications and Disney demonstrates the complex and evolving relationships among studios, networks, streaming services, and cable providers. Even established players like Disney are forced to navigate a precarious transformation of the industry, and it’s unclear which companies and business models will ultimately prevail.

Meanwhile, the very unions that have recently been complaining about consolidation recently won major concessions from the studios and streamers. These might have been salutary—and to some extent, they reflect precisely the underlying industry changes that have otherwise plagued streamers and studios. But they nevertheless impose further constraints on those firms’ profitability and flexibility.

They also serve to undermine claims of labor-market monopsony or undue “buying power” in these sectors. There is widespread acknowledgment, even among the guilds themselves, that these unions have secured substantial (“exceptional,” according to WGA; “historic,” according to SAG-AFTRA) improvements in wages, working conditions, and AI-related commitments. Such gains would be improbable if the industry landscape resembled the dire scenario of unfettered “gatekeeper” power the WGAW asserts as a looming threat.

Beyond that, the guild’s cherry-picked examples don’t even support its case very well. WGAW’s analysis examined several significant market transactions, with particular focus on AT&T’s series of high-profile deals: its acquisition of DirecTV, subsequent purchase of Time Warner, and the eventual spinoff resulting in Warner Bros. Discovery, marking AT&T’s exit from the media business.

Contrary to predictions that Warner Bros. Discovery would emerge as a dominant market force, the company now faces significant challenges. These difficulties stem not from competition with larger, more powerful entities, but rather from substantial debt concerns and Wall Street’s unease regarding its streaming strategy and the future of its legacy linear cable assets.

Similarly, Paramount’s just-announced (and long-awaited) deal with Skydance has been met with tepid support on Wall Street, given the difficult industry conditions even a larger company faces. As TD Cowen analyst Doug Creutz put it: “We don’t think the deal significantly impacts competitive positioning or changes exposure to industry headwinds.”

Conclusion

Simplistic narratives of market consolidation and “gatekeeper” power do not capture the economic realities of today’s streaming-video market. Surely, it is correct that writers (like everyone else in the business) face real challenges in this evolving landscape. Content providers, streaming services, digital platforms, cable providers, broadband providers, TV networks—and, yes, writers, actors, directors, and producers—are all navigating an unpredictable and inordinately complex market shift in technology, business models, and consumer preferences.

What we’re witnessing is not the consolidation of power, but rather the natural evolution of a dynamic and innovative industry. The transition to a new media ecosystem, driven by streaming, brings with it a host of opportunities and challenges. As the industry evolves, it will find a new equilibrium where content creation, distribution, and monetization are balanced to reflect consumers’ changing preferences and habits. There will inevitably be growing pains along the way.

The vast changes in the media marketplace in such a short timeframe should caution against bold predictions about market power, and the WGAW’s report falls far short of a tenable case that Disney+, Amazon, and Netflix (or any others) are the new gatekeepers of some emerging media-ecosystem dystopia. While business challenges exist, they require room for experimentation and innovation, not heavy-handed antitrust intervention based on speculative fears.